Quote of the Day

”It isn’t normal to know what we want. It is a rare and difficult psychological achievement.”

- Abraham Maslow (he of the famous ‘hierarchy of needs’)

Reminds me of Geoffrey Vickers, the wisest man I ever knew. In a conversation towards the end of his long life he said to me, “The hardest thing in life is to know what to want; most people never figure it out, so they wind up pretending that they wanted what they could get”.

Musical alternative to this morning’s news

Ringo Starr, Robbie Robertson and a host of other musicians in a terrific Internet-wide performance of ‘The Weight’

If this isn’t an alternative to the news, then I don’t know what is. Fans of the movie Easy Rider will doubtless remember the tune.

Sharpies, Covid and re-opening schools

Astonishing post in McSweeney’s by a teacher in the US.

I’m thinking about one Sharpie pen in particular. It’s black, medium thickness. And it stays in the blue emergency bag that I keep on the filing cabinet closest to my classroom door. Our school’s emergency bags are remarkably sparse. No band-aids, no first aid materials. We have one flashlight, one sign with my name to help my students find our class if they get separated during a mass exodus, one copy of my class rosters, and one Sharpie marker. Why a marker? Someone asked that very question at a staff meeting. The nurse explained, in a completely emotionless tone, that the Sharpie was so we could identify students and write their names on their bodies in the event of an incident.

She was vague, but we all knew exactly what she was saying. You have a marker in case someone armed with a military-style assault rifle strolls onto campus and starts murdering your co-workers and students. When the shooting stops, we need you to walk through the carnage of your classroom, checking for signs of life. And where there is none, take out that marker and write the name of that precious child, that beautiful life snuffed out too early. She didn’t tell us where we were supposed to write the name — on an arm? A leg? But nobody asked any more questions. We shuffled out of the library silently.

That Sharpie tells me everything I need to know about teaching through COVID. We could have poured resources into prevention. We could’ve spent all summer enforcing mask use and social distancing. We could’ve sacrificed small pleasures for the greater good. We could’ve kept this from happening. But instead, we’re blindly barreling toward reopening even though we know teachers and students will die. We’re going to treat COVID the same way we treat school shootings. An unfortunate but unavoidable cost to doing business. There will be some new morbid addition to the emergency bag. Some simple tool made macabre by the expectation for its use. And like we always do, we will ask our teachers to stand in the doorways and use our bodies as human shields. And if we make it out alive, we’ll be the ones tasked with walking through the wreckage and counting the bodies.

How Covid is hollowing out ‘unsustainable’ Manhattan

Interesting (but not surprising) NYT piece.

[Image credit: New York Times]

For four months, the Victoria’s Secret flagship store at Herald Square in Manhattan has been closed and not paying its $937,000 monthly rent. “It will be years before retail has even a chance of returning to New York City in its pre-Covid form,” the retailer’s parent company recently told its landlord in a legal document.

Wow! A million bucks a month in rent! How much lingerie do you have to sell to justify that?

(Full disclosure: I’ve never been in a Victoria’s Secret store, so I don’t know what her secret was/is. Clearly I should have got out more when I still could.)

Democracy for losers

Long read of the Day.

Remarkable essay by Jan-Werner Müller which puts Trump’s pre-emptive strikes against the legitimacy of the forthcoming election in context.

The TL;DR summary is: since populist politians represent “the people” they cannot, by definition, be the losers in an election. So if, in fact, they lose, then the election must be rigged.

The most interesting part of the essay is his exploration of the fact that democracy only works if the losers accept that they’ve lost. And of course this is also its great weakness, if there are parties around who refuse the accept the possibility that the people might have chosen others than them.

Worth reading in full. Müller’s book on populism is very good, btw.

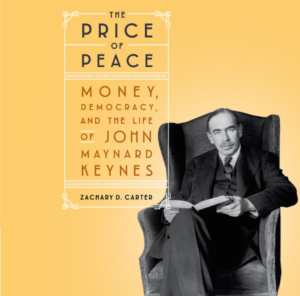

Summer reading #2

Zachary Carter’s life of Keynes is the best biography I’ve read in years. Admittedly, this may be a reflection of the fact that I’ve been fascinated by Keynes for a very long time. I learned a lot about the man that I should have known but didn’t, and it gave me the context I lacked when I first embarked, many years ago, on Keynes’s General Theory.

In fact — as a wise and scholarly friend of mine observed — it’s really two biographies, because Keynes dies about half way through: the first is a biography of the man; the second is a biography of Keynesianism, the economic (and democratic) philosophy that he inspired. Both ‘books’ matter, and the second really helps one to understand how the world we inhabit today was shaped.

One of the things I was grateful to the lockdown for was that it gave me the time — and the excuse — to read this terrific work.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!