Tulip mania

A shaft of sunlight suddenly alighted on them the other morning.

Quote of the Day

”I think that AI will probably, most likely, sort of lead to the end of the world. But in the meantime, there will be great companies created with serious machine learning.”

I guess Altman was trolling his audience at the time. Or was he? One never known with him.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Ye Vagabonds | Danny

Link

Accompanied by a sombre video.

Long Read of the Day

2025 letter | Dan Wang

2025 letter | Dan Wang

For many years, when Dan Wang was a tech analyst living and working in Beijing, his annual letter was invariably one of the great reads of the year. And then there was none. In 2024 He had moved back to the US and (it turned out) was hard at work writing Breakneck, his magisterial comparison of China and the US, which has been a big and much-discussed seller. And then, suddenly, his annual letter is back.

It’s quite long but IMO as good a read as ever.

Here’s how it opens:

One way that Silicon Valley and the Communist Party resemble each other is that both are serious, self-serious, and indeed, completely humorless.

If the Bay Area once had an impish side, it has gone the way of most hardware tinkerers and hippie communes. Which of the tech titans are funny? In public, they tend to speak in one of two registers. The first is the blandly corporate tone we’ve come to expect when we see them dragged before Congressional hearings or fireside chats. The second leans philosophical, as they compose their features into the sort of reverie appropriate for issuing apocalyptic prophecies on AI. Sam Altman once combined both registers at a tech conference when he said: “I think that AI will probably, most likely, sort of lead to the end of the world. But in the meantime, there will be great companies created with serious machine learning.” Actually that was pretty funny.

It wouldn’t be news to the Central Committee that only the paranoid survive. The Communist Party speaks in the same two registers as the tech titans. The po-faced men on the Politburo tend to make extraordinarily bland speeches, laced occasionally with a murderous warning against those who cross the party’s interests. How funny is the big guy? We can take a look at an official list of Xi Jinping’s jokes, helpfully published by party propagandists. These wisecracks include the following: “On an inspection tour to Jiangsu, Xi quipped that the true measure of water cleanliness is whether the mayor would dare to swim in the water.” Or try this reminiscence that Xi offered on bad air quality: “The PM2.5 back then was even worse than it is now; I used to joke that it was PM250.” Yes, such a humorous fellow is the general secretary.

It’s nearly as dangerous to tweet a joke about a top VC as it is to make a joke about a member of the Central Committee. People who are dead serious tend not to embody sparkling irony. Yet the Communist Party and Silicon Valley are two of the most powerful forces shaping our world today. Their initiatives increase their own centrality while weakening the agency of whole nation states. Perhaps they are successful because they are remorseless…

Hope you enjoy it as much as I did. He’s knowledgeable, witty and clearly enjoys long-form writing.

Call my AI agent! Chatbots can now post on their own version of Reddit

My Observer column of 6 February.

In the “old” AI regime, you asked ChatGPT questions and it replied; if you wanted it to think about a complicated matter, you had laboriously to craft a prompt that would guide it along the relevant channels to come up with an answer. In the brave new regime, however, you would simply set a goal and the agent would plan, act, use software tools, check results and adapt to changed circumstances as needed. Rather like a conscientious intern, in fact.

At this point, the corporate hive mind woke up and began salivating: this could mean that AI could replace entire workflows! Wow! If AI could do things end-to-end, then the technology may finally start creating real economic “value” (AKA profits). Verily, agentic AI was the future.

The corporate hive mind’s colleagues in its legal department were not as enthusiastic, though. Responding to prompts is one thing, they would point out, but acting in the world is different. It raises tricky questions about responsibility and legal liability, not to mention the attention of investigative journalists, regulators and other pesky outsiders. So calm down was the advice; let’s not rush down this agentic slipway.

And then, out of the blue, up pops Moltbook, a new social media platform, but one with a radical difference: humans are barred from it. Only verified AI agents – chiefly those powered by OpenClaw software – can participate…

Read on

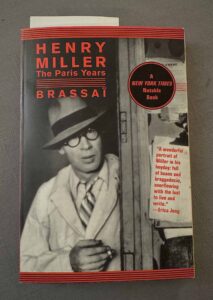

Books, etc.

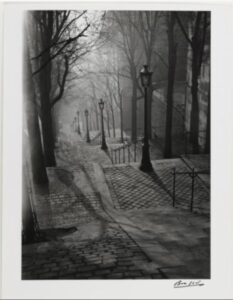

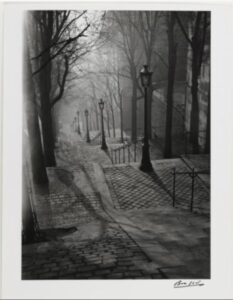

As a photographer, I’ve always been fascinated by Brassai, the pseudonym of Gyula Halász, a Transylvanian journalist and photographer who moved to Paris in 1924 and lived there for the rest of his life. I first came across him via his 1933 book, Paris by Night, in which he published some of the photographs he had taken as he wandered the streets of the city late at night.

His photograph Les Espaliers de Montmartre has pride of place in our dining room, and — like many others — I’ve made unsuccessful efforts to photograph the same scene, consoling myself that things have changed a lot since the 1930s!

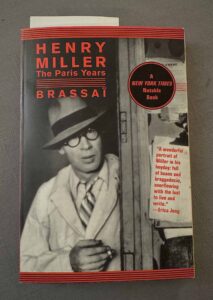

Screenshot

What I hadn’t realised until recently was that Brassai was a friend of Henry Miller, of whom he wrote this biography. It’s an entertaining read, which may be one reason why Miller criticised it as being “padded”, “full of factual errors, full of suppositions, rumors, documents he filched which are largely false or give a false impression.” This might also be the reason why it’s turning out to be such a good read!

My commonplace booklet

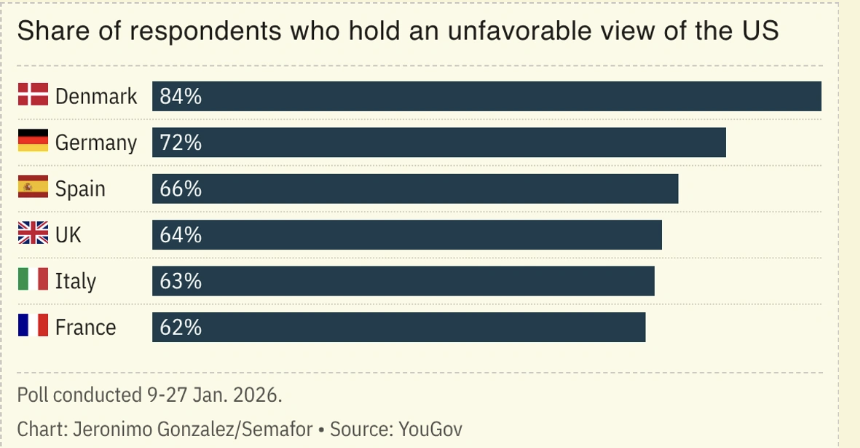

When the depredations of ICE started in the US after Trump’s inauguration, people in the UK comforted themselves with the thought that well, that sort of stuff couldn’t happen here. Rule of law and all that, old boy.

Well, think again. Steve Bloomfield had a sobering piece in the Observer on February 1.

On the eve of last October’s Conservative party conference, its press office highlighted the week’s key announcement. As part of its plan to “tackle the crisis at the borders”, a Tory government would establish “a removals force” that would round up and remove people who were “in the UK illegally or whose visas have expired”.

“Legal barriers” would be removed, resources would be doubled, and the number of people deported each year would rise from 34,000 to around 150,000. The Tories were playing catch-up. Two months earlier, Reform UK had announced its own “mass deportation” plan.

For the past two decades, much of the immigration debate in Europe has been about borders – preventing people from coming in the first place. But over the past year or so, the emphasis has shifted towards deportations. The idea of “remigration” has moved from the far-right fringe to the rightwing mainstream in several European countries. Too many people have come to Europe, they argue, and many of them don’t share what they euphemistically term “European values”.

What began as a threat to those who are undocumented swiftly shifted to encompass those who have followed every rule and have a legal right to live in their new country. In the words of Katie Lam, a Conservative MP who has been tipped as a future leader, some people who are legally entitled to live in Britain “need to go home” in order to ensure the UK remains “culturally coherent”…

You see where this is heading.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!