A royal enclosure

On our cycle-ride this afternoon we passed Childerley Hall, a substantial country house dating from the early 17th century. It was the house where King Charles I was held overnight in June 1647 while being taken from Northamptonshire to Newmarket. Charles was executed two years later.

Click on the image for a larger version.

Tough times ahead for UK universities

From today’s Financial Times:

About a dozen universities could be at risk of insolvency because of the coronavirus pandemic, with a potential drop in the number of students and mounting pension liabilities leaving the sector facing an unprecedented financial crisis.

With losses across higher education totalling anywhere between £3bn and £19bn, or between 7.5 per cent and half of overall annual income, some institutions may be unable to survive without a targeted government bailout, according to research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies think-tank…

Martin Wolf and the relevance of Aristotle

It is clear then that the best partnership in a state is the one which operates through the middle people, and also that those states in which the middle element is large, and stronger if possible than the other two together, or at any rate stronger than either of them alone, have every chance of having a well-run constitution.”

- Aristotle, Politics

Martin Wolf has a wonderful essay in today’s FT in which he applies Aristotle’s insight into the recent history of liberal democracies. I’m not sure if the link is behind a paywall today, but recently the FT has been good about lowering the wall on pieces like this which enrich the public sphere.

239 Experts With One Big Claim: The Coronavirus is airborne

Really important report.

The coronavirus is finding new victims worldwide, in bars and restaurants, offices, markets and casinos, giving rise to frightening clusters of infection that increasingly confirm what many scientists have been saying for months: The virus lingers in the air indoors, infecting those nearby.

If airborne transmission is a significant factor in the pandemic, especially in crowded spaces with poor ventilation, the consequences for containment will be significant. Masks may be needed indoors, even in socially-distant settings. Health care workers may need N95 masks that filter out even the smallest respiratory droplets as they care for coronavirus patients.

Ventilation systems in schools, nursing homes, residences and businesses may need to minimize recirculating air and add powerful new filters. Ultraviolet lights may be needed to kill viral particles floating in tiny droplets indoors.

The World Health Organization has long held that the coronavirus is spread primarily by large respiratory droplets that, once expelled by infected people in coughs and sneezes, fall quickly to the floor.

But in an open letter to the W.H.O., 239 scientists in 32 countries have outlined the evidence showing that smaller particles can infect people, and are calling for the agency to revise its recommendations. The researchers plan to publish their letter in a scientific journal next week.

It’s frustrating to see how slowly the world converges on obvious common sense. For the foreseeable future the only way of having a hope of some kind of normality is for people to wear masks whenever they’re in an indoor space with non-family members. How long will it take for this penny to drop.

Use juries on social media decisions

Jonath Zittrain has had a good idea:

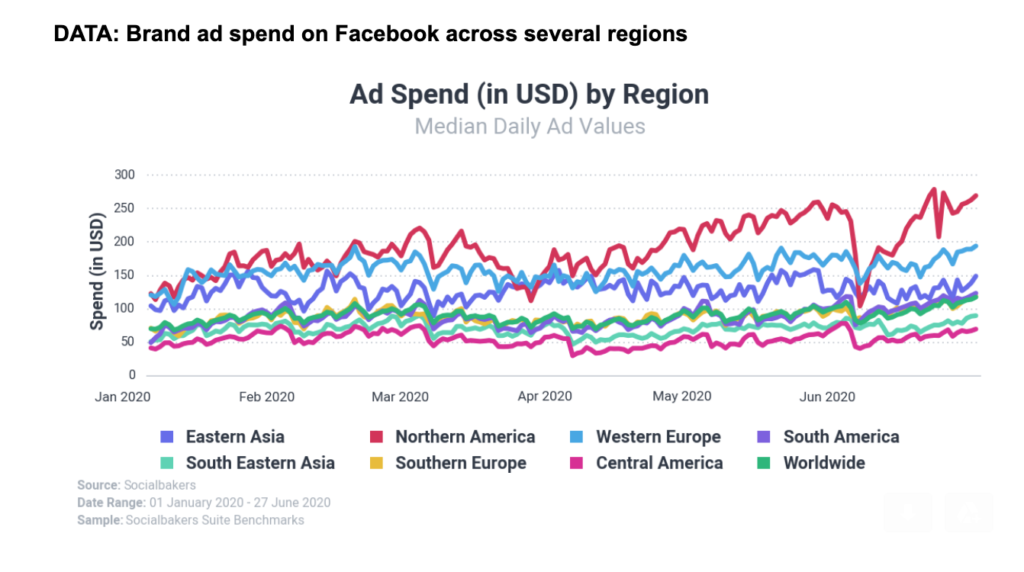

No matter how Facebook and its counterparts tweak their policies, whatever these companies do will prompt broad anxiety and disapprobation among experts and their own users. That’s because there are two fundamental problems underlying the debate. First, we the public don’t agree on what we want. And second, we don’t trust anyone to give it to us. At one moment someone can reasonably question how Facebook thinks itself king, deciding what each of its 2.4 billion users can see or post—and at another ask how Facebook can make a profit of $22 billion a year from distributing others’ content, and yet take no consistent responsibility for what’s inside it.

What we need are ways for decisions about content to be made, as they inevitably must be when platforms rank and recommend content for us to see; for those decisions yet not to be too far-reaching or stiflingly consistent, so there is play in the joints; and for the deep stakes of those decisions to be matched by the gravity and reflectiveness of the process to make them. Facebook recently announced plans for an “independent oversight board,” a tribunal that would render the company’s final judgment on whether a disputed posting should be taken down. But far more than its own version of the Supreme Court, Facebook needs a way to tap into the everyday common sense of regular people. Even Facebook does not trust Facebook to decide unilaterally which ads are false and misleading. So if the ads are to be weighed at all, someone else has to render judgment.

In the court system, legislators write laws, and lawyers argue cases, but juries of ordinary people are typically the finders of fact and judges of what counts as “reasonable” behavior. This is less because a group of people plucked from the phone book is the best way to ascertain truth—after all, we don’t use that kind of group for any other fact-finding. Rather, it’s because, when done honorably, with duties taken seriously, deliberation by juries lends legitimacy and credibility to the machinations of the legal system.

I think this is a great idea. I was once a juror on a really serious criminal case and I was blown away by the way in which a group of twelve ‘ordinary’ people was able to sort through a maze of contradictory and flawed evidence and patiently and thoroughly come to a decision. And then to discover afterwards that it was exactly the correct conclusion, because the previous criminal record of the accused had — of course — not been disclosed to us.

Of course juries sometimes get it wrong. But so do judges, sometimes. No system is perfect, but the jury system has been going for centuries and it has served law-abiding societies well.

How to run a Zoom webinar

If you have any aspiration or need to run a Zoom webinar competently and successfully (and I’ve seen a few car-crash examples of how not to do it in recent weeks) then this comprehensive check-list by my friend Quentin is a must-read. Pass the link on to anyone you think might need it.

All Harvard University students will take online classes this fall amid coronavirus

Some students will live on campus but all lectures will be online.

So reports the Boston Herald.

Harvard University is allowing some students to live on campus this fall amid coronavirus, but all classes will be taught online, the university announced on Monday.

“… All course instruction (undergraduate and graduate) for the 2020-21 academic year will be delivered online,” Harvard officials wrote to the campus community. “Students will learn remotely, whether or not they live on campus.”

While most students will live at home, Harvard plans to bring up to 40% of its undergraduates to campus, including all first-year students.

“This will enable first-year students to benefit from a supported transition to college-level academic work and to begin to build their Harvard relationships with faculty and peers,” the officials wrote. “Both online and dorm-based programs will be in place to meet these needs. Over the last few weeks, there has been frequent communication with our first-year students about their transition to Harvard and this will continue as we approach the start of the academic year.”

Oddly enough, there’s no mention of a reduction in tuition fees. So as one American university student commented to the WSJ the other day (and it’s not clear what university he had in mind): “It’s like paying $75000 for a ticket to see Beyoncé and then being told you’ve got a livestream instead”. Neat way of putting it, eh?

I hate to say it, but all this was foreseen by Eli Noam in his wonderful paper, “Electronics and the Dim Future of the University”. When was it published? Why, 1995.

How Trump can lose the election and still cling to power

My friends think I’m neurotic, but I can’t see Trump accepting defeat and going quietly. And when I ask “Well, who exactly would remove him — if need be physically — from the White House?” I don’t get an answer. So you can see why this piece in Newsweek grabbed my attention.

This spring, HBO aired The Plot Against America, based on the Philip Roth novel of how an authoritarian president could grab control of the United States government using emergency powers that no one could foresee. Recent press reports have revealed the compilation by the Brennan Center at New York University of an extensive list of presidential emergency powers that might be inappropriately invoked in a national security crisis. Attorney General William Barr, known for his extremist view of the expanse of presidential power, is widely believed to be developing a Justice Department opinion arguing that the president can exercise emergency powers in certain national security situations, while stating that the courts, being extremely reluctant to intervene in the sphere of a national security emergency, would allow the president to proceed unchecked.

Something like the following scenario is not just possible but increasingly probable because it is clear Trump will do anything to avoid the moniker he hates more than any other: “loser.”

Trump actually tweeted on June 22: “Rigged 2020 election: millions of mail-in ballots will be printed by foreign countries, and others. It will be the scandal of our times!” With this, Trump has begun to lay the groundwork for the step-by-step process by which he holds on to the presidency after he has clearly lost the election…

The authors (a former US Senator for Colorado and a senior journalist who was once senior counsel to a congressional committee) then lay out a 12-stage scenario for how the nightmare could unfold.

Worth reading unless you are of a nervous disposition.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!