New England in the Fall

Jason Kottke, the Über Blogger lives in Vermont. He posted this astonishing image on his blog the other day. It makes one realise that the English Autumn, though beautiful in its way, is pretty muted by comparison.

Quote of the Day

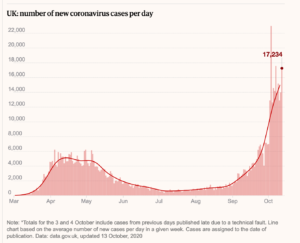

“It seems to people who are on lockdown that it’s going on interminably, but for scientists it’s just the beginning. We are still just scratching the surface of this.”

- Dr. Martha Nelson, a scientist at the US National Institutes of Health who specializes in epidemics and viral genetics, quoted in today’s New York Times piece marking the sombre milestone of a million Covid deaths worldwide.

Yep: we’re in a marathon, not a sprint.

Musical replacement for the morning’s radio news

Schubert – Impromptu #3: Vladimir Horowitz, live performance in Vienna, in 1987 (I think)

Link

Audio quality is not great, but it’s a lovely performance. Amazing to see the way he seems almost to caress the keyboard with those long fingers of his.

How To Plan For The Post-Covid Future

Long read of the day

Tim O’Reilly is one of the smartest people I know. And this essay is worth your time IMHO:

The 20th century didn’t really begin in the year 1900, it began in 1914, when the assassination of Austrian Archduke Ferdinand triggered long-simmering international tensions and the world slid, seemingly inexorably, into a great world war, followed by a roaring return to seeming normality and then a crash into a decade-long worldwide depression and another catastrophic war. Empires were dissolved, an entire way of life swept away. A new, more prosperous world emerged only through the process of rebuilding a society that had been torn down to its foundations.

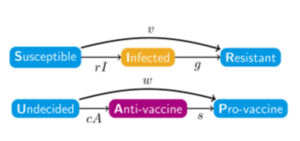

So too, when we look back, we will understand that the 21st century truly began this year, when the COVID19 pandemic took hold. We are entering the century of being blindsided by things that we have been warned about for decades but never took seriously enough to prepare for, the century of lurching from crisis to crisis until, at last, we shake ourselves from the illusion that our world will go back to the comfortable way it was and begin the process of rebuilding our society from the ground up.

Even when we develop a successful COVID19 vaccine or treatment, or when we achieve herd immunity, this will not be the last pandemic. Other long-predicted but “unexpected” crises lurk in the wings: flooding, drought, mass migrations, food shortages, and wars as a result of climate change; widespread antibiotic resistance due to overuse on factory farms; political instability driven by an unsustainable level of economic inequality; crumbling infrastructure and lack of investment in bettering the lives of ordinary citizens at the expense of a feverish Ponzi economy focused on growing asset values for the wealthy.

So, when you read stories—and there are many—speculating or predicting when and how we will return to “normal”, discount them heavily. The future will not be like the past. The comfortable Victorian and Georgian world complete with grand country houses, a globe-spanning British empire, and lords and commoners each knowing their place, was swept away by the events that began in the summer of 1914 (and that with Britain on the “winning” side of both world wars.) So too, our comfortable “American century” of conspicuous consumer consumption, global tourism, and ever-increasing stock and home prices may be gone forever.

[…]

Our failure to make deep, systemic changes after the financial collapse of 2009, and our choice instead to spend the last decade cutting taxes and spending profusely to prop up financial markets while ignoring deep, underlying problems has only made responding to the current crisis that much more difficult. Our failure to build back creatively and productively from the global financial crisis is necessary context for the challenge to do so now…

Thoughtful, far-reaching and not necessarily reassuring.

Former Facebook manager: “We took a page from Big Tobacco’s playbook”

Well, well. For a long time I’ve been likening the surveillance capitalist companies to tobacco and oil companies. But I never thought I’d hear a former Facebook employee state that he once saw the analogy as a guide to policy. Yet here is Tim Kendall, who served as director of monetization for Facebook from 2006 through 2010, speaking to Congress on September 24 as part of a House Commerce subcommittee hearing examining how social media platforms contribute to the mainstreaming of extremist and radicalizing content.

He told legislators that the company “took a page from Big Tobacco’s playbook, working to make our offering addictive at the outset” and arguing that his former employer has been hugely detrimental to society.

“The social media services that I and others have built over the past 15 years have served to tear people apart with alarming speed and intensity,” Kendall said in his opening testimony. “At the very least, we have eroded our collective understanding—at worst, I fear we are pushing ourselves to the brink of a civil war.”

“We sought to mine as much attention as humanly possible… We took a page form Big Tobacco’s playbook, working to make our offering addictive at the outset.”

Tobacco companies initially just sought to make nicotine more potent. But eventually that wasn’t enough to grow the business as fast as they wanted. And so they added sugar and menthol to cigarettes so you could hold the smoke in your lungs for longer periods. At Facebook, we added status updates, photo tagging, and likes, which made status and reputation primary and laid the groundwork for a teenage mental health crisis.

Allowing for misinformation, conspiracy theories, and fake news to flourish were like Big Tobacco’s bronchodilators, which allowed the cigarette smoke to cover more surface area of the lungs. But that incendiary content alone wasn’t enough. To continue to grow the user base and in particular, the amount of time and attention users would surrender to Facebook, they needed more.

“We initially used engagement as sort of a proxy for user benefit. But we also started to realize that engagement could also mean [users] were sufficiently sucked in that they couldn’t work in their own best long-term interest to get off the platform… We started to see real-life consequences, but they weren’t given much weight. Engagement always won, it always trumped.”

“There’s no incentive to stop [toxic content] and there’s incredible incentive to keep going and get better. I just don’t believe that’s going to change unless there are financial, civil, or criminal penalties associated with the harm that they create. Without enforcement, they’re just going to continue to be embarrassed by the mistakes, and they’ll talk about empty platitudes… but I don’t believe anything systemic will change… the incentives to keep the status quo are just too lucrative at the moment.”

Wow!

Florida Police Just Released Video of Brad Parscale Getting Tackled by Cops

Well, well. How are the mighty fallen.

Some background:

You may remember that Brad Parscale was the supposed genius behind the 2016 Trump campaign’s weaponisation of Facebook. This made him a kind of global political celebrity — worth even a big profile in the New Yorker, no less as “The man behind Trump’s Facebook juggernaut”. Come 2020 and Parscale was now the Director of the Trump campaign and an even more swaggering giant. He was the driving spirit behind the ludicrous Tulsa rally — the one that supposedly had 800,000 pre-registrations. Except, of course, that it didn’t. The Trump operation had been cleverly hijacked by kids on TikTok who made fake pre-bookings. So the rally was a fiasco, at which point I predicted that Parscale’s days as Director were numbered. It was an accurate prediction — he was replaced in July by Bill Stepien.

Now spool forward to the present. Here’s a report by Vice News from Fort Lauderdale in Florida, where Parscale reportedly owns three houses:

Police in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, just released a video of President Trump’s former campaign manager getting tackled by cops.

The body camera footage shows a police officer hurling Parscale to the ground during an incident at his home, shortly after they responded to a call for help from Parscale’s wife. She told police that Parscale had threatened to kill himself and had racked the slide of a handgun in front of her face, “putting her in fear for her safety,” according to a police report.

The video shows Parscale, wearing white shorts and no shirt, speaking with a police officer, and then another officer rapidly approaches Parscale from his right side, telling him, “Get on the ground, man.”

Parscale doesn’t visibly react to that command at first. The police officer then hurls him to the ground, while Parscale objects, saying “I didn’t do anything.”

One doesn’t want to intrude on private grief, but it looks as though Parscale has had some kind of breakdown. CBS reports that he “was taken to a mental health facility in Florida on Sunday night after barricading himself in his home with weapons and threatening to harm himself, police said. Parscale was detained without injury and transported to a local hospital.”

Nobody works for Trump without in the end being damaged by the experience.

How Much Has Inequality Cost Workers?

From a sobering piece in the Journal of Democracy, especially for those who are nostalgic for a return to our current version of capitalism-friendly democracy.

Even if Donald Trump loses the election, the conditions that made his authoritarian regime possible won’t disappear with him. If we are to heal our country and ensure against a repeat of the past four years, we need to boldly and aggressively scale our solutions to the size of the problem. And when it comes to our crisis of rising income inequality, the problem is huge.

How big is it? A staggering $50 trillion.

That’s how much the upward redistribution of income has cost American workers over the past several decades.

This is not some back-of-the-napkin approximation. According to a groundbreaking new working paper by Carter C. Price and Kathryn Edwards of the RAND Corporation, from 1947 through 1974, real incomes grew at close to the rate of per capita economic growth across all income levels. That means that for three decades, those at the bottom and middle of the distribution saw their incomes grow at about the same rate as those at the top. Had these more equitable income distributions merely held steady, the aggregate annual income of Americans earning below the 90th percentile would have been $2.5 trillion higher in the year 2018 alone. That is an amount equal to nearly 12 percent of GDP—enough to more than double median income, and enough to pay every single working American in the bottom nine deciles an additional $1,144 a month. Every worker. Every month. Every. Single. Year.

But the ‘normal’ that our governments wish us to return to is not the normality of 1947-1974, but the post 1974 one.

The RAND paper is here. The Abstract reads:

The three decades following the Second World War saw a period of economic growth that was shared across the income distribution, but inequality in taxable income has increased substantially over the last four decades. This work seeks to quantify the scale of income gap created by rising inequality compared to a counterfactual in which growth was shared more broadly. We introduce a time-period agnostic and income-level agnostic measure of inequality that relates income growth to economic growth. This new metric can be applied over long stretches of time, applied to subgroups of interest, and easily calculated. We document the cumulative effect of four decades of income growth below the growth of per capita gross national income and estimate that aggregate income for the population below the 90th percentile over this time period would have been $2.5 trillion (67 percent) higher in 2018 had income growth since 1975 remained as equitable as it was in the first two post-War decades. From 1975 to 2018, the difference between the aggregate taxable income for those below the 90th percentile and the equitable growth counterfactual totals $47 trillion. We further explore trends in inequality by applying this metric within and across business cycles from 1975 to 2018 and also by demographic group.

The extent of my ignorance

One of the first rules of blogging is always to assume that out there are people who know far more than you do. I’ve adhered to this since Day One (in the mid-1990s) and have never been disappointed. So when the other day I confessed that I hadn’t known that Trump owned a golf-course in Ireland, in no time at all readers wrote in suggesting gently that I really ought to know better. For example, Charles Foster wrote:

You didn’t know that Trump had a golf course in Ireland? Good Lord! It’s at Doonbeg, and has been owned by him for about six years: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trump_International_Golf_Links_and_Hotel_Ireland

The Irish government laid down a red carpet for him when he came to visit in 2015 just after buying it. He’s been here a couple of times (I think) since becoming President, the last time in 2019 when he used it as an overnight stop when he was in France commemorating the 75th anniversary of the D Day landings — this was the time when he didn’t go to the US war cemetery near Paris to pay his respects because it was raining.

To which I can only protest that I did know about Doonbeg, partly because a friend of mine who is a terrific golfer is a member there. But I had no idea that it was owned by Trump and is now — of course — badged under his accursed name!

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!