Gone Fishin’

Cley beach, Norfolk, 2018.

Quote of the Day

”There are two things which I am confident I can do well: one is an introduction to literary work, stating what it is to contain, and how it should be executed in the most perfect manner; the other is a conclusion, shewing from various causes why the execution has not been equal to what the author promised to himself and to the public.”

Rings any bells with you? Does with me.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Beethoven | Für Elise” | Lang Lang

Link

When I lived and worked in Holland in the late 1970s I often went to the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam on Sunday mornings where there would be a recital in the Spiegelzaal. You paid a small fee, got a coffee and found a place to sit. I think these treats were actually branded as Für Elise, but it’s so long ago that I can’t be sure. Still, this wonderful performance by Lang Lang brings it all back.

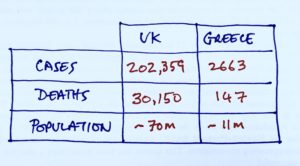

The false promise of herd immunity for COVID-19

Why proposals to largely let the virus run its course — embraced by Donald Trump’s administration and others — could bring “untold death and suffering”.

Useful briefing from Nature which explains the concept and the difficulty of estimating what percentage of a population have it.

It’s complicated, as you might expect. The bottom line, though, is that “never before have we reached herd immunity via natural infection with a novel virus, and SARS-CoV-2 is unfortunately no different.”

Vaccination is the only ethical path to herd immunity. Letting it rip is neither ethical nor likely to be effective.

We kind-of knew that, didn’t we? Except for Trump, of course, who called it “herd mentality”.

Writing to Simone

Terrific review essay by Vivian Gornick in the Boston Review on Simone de Beauvoir and the letters readers wrote to her. The book she’s writing about is Judith Coffin’s Sex, Love, and Letters: Writing Simone de Beauvoir — a work that came out of the author’s discovery of the enormous trove of letters to Beauvoir from her readers in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris.

It was not only, or even mainly, The Second Sex that bound readers to Beauvoir for decades. More than anything it was the memoirs, following one upon another, that accounted for the remarkable loyalty thousands of women, and some men too, showered upon the gradual unfolding of a life lived almost entirely in the public eye, at the same time that its inner existence was continually laid bare and minutely reported upon. Fearless was the word most commonly associated with these books as, in every one of them, Beauvoir, good Existentialist that she was, wrote with astonishing frankness about sex, politics, and relationships. She recorded in remarkable detail, and with remarkable authenticity, everything she had thought or felt at any given moment. Well, kind of. She recorded everything that she was not ashamed of. Years later, after she and Sartre were both dead, appalling behavior came to light that she had either omitted from the memoirs or put a positive spin on.

Sex, Love, and Letters is a richly researched study based on Judith Coffin’s encounter with a batch of these letters that a sympathetic curator put into her hands one day while she was working on The Second Sex in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris. As she writes in her introduction, “Nothing prepared me for the drama I found the first time I opened a folder of readers’ letters to Simone de Beauvoir. . . . What I found was an outpouring of projection, identification, expectation, disappointment, and passion.” Correspondents “asked for advice on marriage, love, and birth control; they confessed secrets and sent sections of their diaries for her to read. The letter writers’ tone was unexpected as well, alternately deferential and defiant, seductive, and wry.”

I know a bit about this because I was once married to a woman whose life was changed by reading the Second Sex and the successive volumes of Beauvoir’s remarkable autobiography. Carol (who died in 2008) was deeply influenced by these texts and for her (and to some extent for me) this amazing French intellectual became a kind of heroine — so much so that Carol later did a Masters thesis on the autobiography. I’m looking at it now as I write. She even wrote to Beauvoir asking for an interview — and went to Paris to see her in her apartment. So I guess her letters are also in the BN’s trove.

As Gornick implies, the passage of time, and posthumous revelations, has taken the shine off the image of Beauvoir and her accomplice in literary celebrity, Jean-Paul Sartre. Subsequent biographies have revealed that they both sometimes behaved abominably towards other people. I guess it leaves those of us who, as impressionable students, were dazzled by them, looking naive. So what? Everybody was young and foolish once. And whatever one thinks about its author with the 20/20 vision of hindsight, The Second Sex was a genuinely pathbreaking book.

There’s a word for why we wear masks, and Liberals should say it

Michael Tomasky has a fine OpEd piece in the New York Times about the way the word “freedom” has been hijacked by the alt-right and their accomplices in the Republican party.

Donald Trump is now back on the road, holding rallies in battleground states. These events, with people behind the president wearing masks but most others not, look awfully irresponsible to most of us — some polls show that as many as 92 percent of Americans typically wear masks when they go out.

Trumpworld sees these things differently. Mike Pence articulated the view in the vice-presidential debate. “We’re about freedom and respecting the freedom of the American people,” Mr. Pence said. The topic at hand was the Sept. 26 super-spreader event in the Rose Garden to introduce Amy Coney Barrett as the president’s nominee for the Supreme Court and how the administration can expect Americans to follow safety guidelines that it has often ignored.

Tomasky goes back to John Stuart Mill (whom many right-wingers apparently revere). In On Liberty he wrote that liberty (or freedom) means “doing as we like, subject to such consequences as may follow, without impediment from our fellow creatures, as long as what we do does not harm them even though they should think our conduct foolish, perverse or wrong.” This is a standard definition of freedom, more succinctly expressed in the adage: “Your freedom to do as you please with your fist ends where my jaw begins.”

Most of the nonsense about mask-wearing in the US is expressed in the language of “my freedom”. It’s ludicrously oxymoronic, though. I saw a fanatical anti-mask woman on TV recently saying “it’s my body and I’m not going to have anyone telling me what to wear on my face” while it was pretty clear that she doesn’t agree with pro-abortion campaigners who maintain “It’s my body and I’m going to decide what happens to it.” Par for the course: fanatics don’t do consistency.

“Freedom,” Tomasky observes,

emphatically does not include the freedom to get someone else sick. It does not include the freedom to refuse to wear a mask in the grocery store, sneeze on someone in the produce section and give him the virus. That’s not freedom for the person who is sneezed upon. For that person, the first person’s “freedom” means chains — potential illness and even perhaps a death sentence. No society can function on that definition of freedom. emphatically does not include the freedom to get someone else sick. It does not include the freedom to refuse to wear a mask in the grocery store, sneeze on someone in the produce section and give him the virus. That’s not freedom for the person who is sneezed upon. For that person, the first person’s “freedom” means chains — potential illness and even perhaps a death sentence. No society can function on that definition of freedom.

He’s right about how strange it is that “freedom” belongs almost wholly to the right. They talk about it incessantly and insist on a link between economic freedom and political freedom, positing that the latter is impossible without the former. (This is a legacy of Hayek and what Philip Mirowski calls the “Neoliberal Thought Collective”.) And yet, as Tomasky says,

the broad left in America has let all this go unchallenged for decades, to the point that today’s right wing can defend spreading disease, potentially killing other people, as freedom. It is madness.

It is.

Dutch Ethical Hacker Logs into Trump’s Twitter Account

From the Dutch newspaper, De Volkskrant.

Last week a Dutch security researcher succeeded in logging into the Twitter account of the American President Donald Trump. Trump, an active Twitterer with 87 million followers, had an extremely weak and easy to guess password and had according to the researcher, not applied two-step verification.

The researcher, Victor Gevers, had access to Trump’s personal messages, could post tweets in his name and change his profile. Gevers took screenshots when he had access to Trump’s account. These screenshots were shared with de Volkskrant by the monthly opinion magazine Vrij Nederland. Dutch security experts find Gevers’ claim credible.

The Dutchman alerted Trump and American government services to the security leak. After a few days, he was contacted by the American Secret Service in the Netherlands. This agency is also responsible for the security of the American President and took the report seriously, as evidenced by correspondence seen by de Volkskrant. Meanwhile Trump’s account has been made more secure.

So what was Trump’s password? Yes — you guessed it! — it was “maga2020!”

Other, perhaps interesting, links

- Doomsday preppers– Link

- The new Hummer. Beyond parody, really but interesting technically. Link

- The Criminal Case Against Donald Trump Is in the Works. Link. No wonder he doesn’t want to lose the Presidency.