Guinea rose

In the garden, this afternoon. Click on the image to see a larger one.

Lunch with Rutger Bregman — outspoken historian and scourge of Davos

Fascinating conversation (which I’m hoping is not behind the paywall) with the ever-interesting Simon Kuper. If you haven’t read Bergman, this this is the time to start. His Utopia for Realists is terrific. I’ve just ordered his Humankind: A Hopeful History.

Bregman at Davos

This is the YouTube recording that went viral (excuse the pun) a while back.

The enduring romance of the night train

Truly lovely New Yorker essay by Anthony Lane.

The departure of a night train—by definition, a humdrum event for the station staff—exudes, for all but the most jaded travellers, the thrill of an unfamiliar ritual. By day, if late, you run for a train; if early, you tut and sigh at having to tarry so long. At night, on the other hand, you saunter, and deliberately show up in good time. Why? Not because of security, passport control, or the other chores that affront the airline passenger, shortening tempers and sapping every soul, but because you want to settle in and enjoy the show. Patiently, the train awaits you, with a theatrical air of suspense, and the moment of its leaving is akin to the curtain’s rise. T. S. Eliot, for one, knew the moment well:

There’s a whisper down the line at 11:39

When the Night Mail’s ready to depart

If, like me, you’re dreaming about being able to travel again, one day, then this is for you.

Tech nations

A perceptive project by Tortoise, an interesting new slow-journalism outfit. Funded by a membership scheme. Their idea: to look at the tech giants as if they were nation-states. First study was of Apple. Second-up The United States of Amazon.

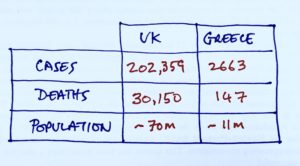

Keep your distance: 2m is much better than 1m; and face masks are also useful

Keeping people 2m apart from each other is far more effective than just one at reducing the risk of spreading coronavirus, according to a new review in The Lancet. The risk of infection when people stand one metre away is 3%, compared with 13% if standing within a metre. The risk of transmission halves for every extra metre of distancing up to three metres, the modelling suggested. The researchers also found that both face coverings and eye protection significantly reduce the risk of spreading the virus.

Well, we kind-of guessed that already (especially about face-masks) but it’s nice to have empirical confirmation.

This is online learning’s moment. For universities, it’s a total mess

The next year is going to be a torrid year for universities everywhere. This Wired story spells it out in gory detail.

With no end to the pandemic in sight, virtual classes are here to stay. They solve the problem of packed lecture halls and hallways that aren’t designed for social distancing – and are also far cheaper to run. But not many people want to pay almost £10,000 a year for the privilege of attending Zoom calls. Many UK universities are bracing for a gaping hole in their budgets as they expect fewer students to turn up in the autumn. A survey found that one in five people were willing to delay their undergraduate degrees if universities were not operating as normal due to the coronavirus pandemic. With 120,000 fewer students starting in September, UK universities could face a £760 million loss of income in tuition fees.

The University of Manchester, which has announced plans to keep lectures online-only in the autumn term, is already preparing for the worst. On April 23, vice-chancellor Dame Nancy Rothwell told staff that redundancies and pay cuts may be necessary if 80 per cent of students from outside the EU and 20 per cent of UK and EU students decided to stay defer or drop out. In the worst-case scenario, the university could lose up to £270m in a single year – a 15 to 25 per cent deficit.

The University of Cambridge (where I work) has decided that the 2020-21 academic year will be entirely online. It’s hard to say how this will work out, but it could be a shrewd decision because it offers an opportunity for teaching staff to really prepare for an online year — rather than having frantically to cobble something together, as they have been doing this year.

For undergraduate teaching in some subjects, Cambridge (and Oxford) may be in a good position to make this work. This is partly because lectures are only one of the teaching media offered in those two universities. Undergraduates also get tutored in small-group teaching organised by their colleges. I’m pretty sure that some humanities students in the past have obtained good degrees without ever attending a university lecture in Cambridge. (Stephen Fry may be one of them, if I’ve read his memoir correctly.) So Cambridge can have online lectures that are better designed than being just re-purposed face-to-face ones; and the college tutorial system can work online, because, for example, Zoom is pretty good for small-group seminar-type teaching which can mimic the current system.

But that only applies to the Humanities and Social Sciences. For engineering, materials science, chemistry, biology and similar disciplines laboratory experience is pretty crucial. Maybe that can be reorganised with social distancing. But it’ll be harder to do.

And of course, looming over this, is the question of whether students will be willing to incur substantial debt accruing from £10,000 fees for a purely online experience? Maybe they will for some universities, because of the value of the “positional goods” provided by elite institutions. But for other, perfectly respectable but non-elite schools…? I wonder.

But while we’re on the subject of universities in peril…

The University of Texas at Arlington has a free edX course for teachers who need to switch to teaching online. It “explores research-informed, effective practices for online teaching and learning, providing guidance on how to pivot existing courses online while enhancing student success and engagement”. I know the research of some of the people involved and think it might be worth considering… And while target audience is obviously people working in post-secondary institutions, the course could conceivably be of use to anyone moving into online teaching and learning.

Quarantine diary — Day 73

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if your decide that your inbox is full enough already!