Atul Gawande on managing Covid

He’s the best writer on medical issues I know. Last May he wrote a really useful essay in the New Yorker. I’ve just re-read it in the light of what’s happened since. It still stands out.

Two samples:

American hospitals have learned how to avoid becoming sites of spread. When the time is right to lighten up on the lockdown and bring people back to work, there are wider lessons to be learned from places that never locked down in the first place.

These lessons point toward an approach that we might think of as a combination therapy—like a drug cocktail. Its elements are all familiar: hygiene measures, screening, distancing, and masks. Each has flaws. Skip one, and the treatment won’t work. But, when taken together, and taken seriously, they shut down the virus. We need to understand these elements properly—what their strengths and limitations are—if we’re going to make them work outside health care.

Start with hygiene. People have learned that cleaning your hands is essential to stopping the transfer of infectious droplets from surfaces to your nose, mouth, and eyes. But frequency makes a bigger difference than many realize…

and

A recent, extensive review of the research from an international consortium of scientists suggests that if at least sixty per cent of the population wore masks that were just sixty-per-cent effective in blocking viral transmission—which a well-fitting, two-layer cotton mask is—the epidemic could be stopped. The more effective the mask, the bigger the impact.

Coronavirus and the dim future of (many) American universities

Scott Galloway may not be to everyone’s taste, but I like the way he thinks — and, more importantly, the stark way in which he analyses things.

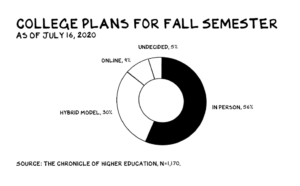

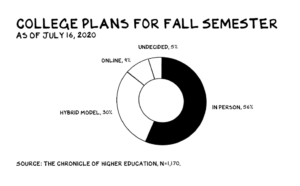

This week he’s been looking at this chart (from the Chronicle of Higher education) which summarises a survey of US colleges’ intentions for the next academic year.

The relevant statistic is the 56% which apparently plan to bring student back to campus in the Fall.

The graphic below neatly summarises what this means.

Think about this. Next month, as currently envisioned, 2,800+ cruise ships retrofitted with white boards and a younger cohort will set sail in the midst of a raging pandemic. The density and socialization on these cruise ships could render college towns across America the next virus hot spots.

So why are administrators putting the lives of faculty, staff, students, and our broader populace at risk?

The ugly truth is many college presidents believe they have no choice. College is an expensive operation with a relatively inflexible cost structure. Tenure and union contracts render the largest cost (faculty and administrator salaries) near immovable objects. The average salary of a professor with a PhD (before benefits and admin support costs) is $141,476, though some make much more, and roughly 50% of full-time faculty have tenure. While some universities enjoy revenue streams from technology transfer, hospitals, returns on multibillion dollar endowments, and public funding, the bulk of colleges have become tuition dependent. If students don’t return in the fall, many colleges will have to take drastic action that could have serious long-term impacts on their ability to fulfill their missions.

That gruesome calculus, Galloway says, has resulted in “a tsunami of denial”.

Universities owning up to the truth have one thing in common: they can afford to. Harvard, Yale, and the Cal State system have announced they will hold most or all classes online. The elite schools’ endowments and waiting lists make them largely bullet proof, and more resilient to economic shock than most countries — Harvard’s endowment is greater than the GDP of Latvia. At the other end of the prestige pole, Cal State’s reasonable $6,000 annual tuition and 85% off-campus population mean the value proposition, and underlying economic model, remain largely intact even if schooling moves online.

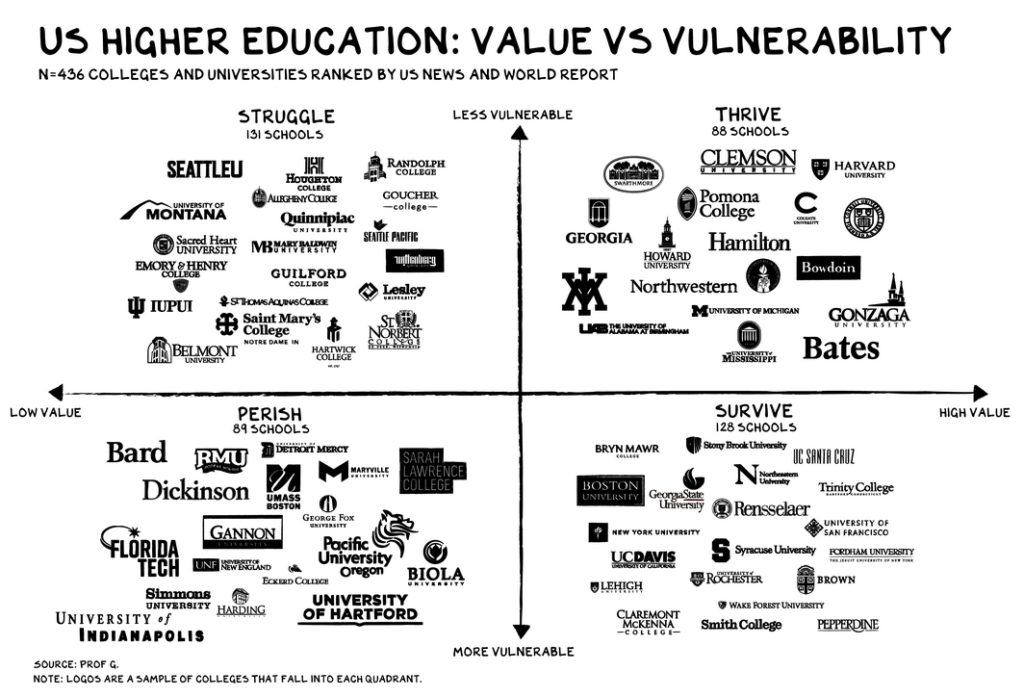

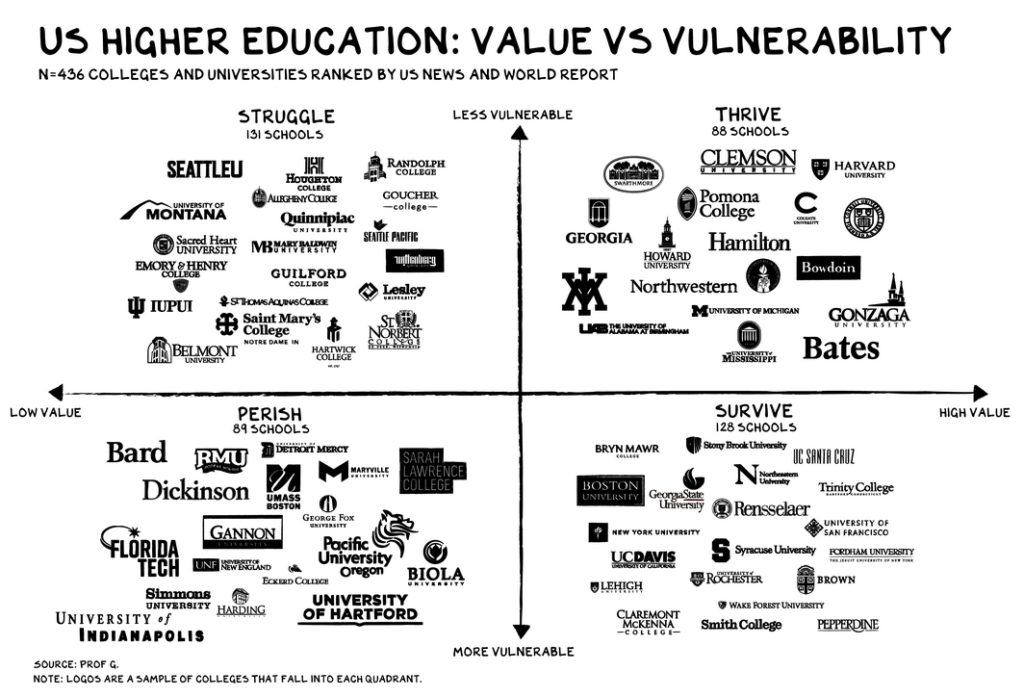

Galloway and his team have analysed the prospects of 436 universities and then plotted their prpspects on two axes:

Value: (Credential * Experience * Education) / Tuition. Vulnerability: (Endowment / Student and % International Students). Low endowment and dependence on full-tuition international students make a university vulnerable to Covid shock, as they may decide to sit this semester/year out.

Which produces this grid:

Now of course the US Higher Education system is very different from the UK’s. But it’d be interesting to see what an analogous analysis of UK universities would show.

EU court rejects data transfer tool in Max Schrems case

This is the big story of the week (at least in the bubbles I inhabit)…

From The Irish Times:

Europe’s top court has declared an arrangement under which companies transfer personal data from the European Union to the US invalid due to concerns about US surveillance powers.

The ruling in the long-running battle between Facebook, Ireland’s Data Protection Commissioner and the Austrian privacy activist Max Schrems found that the so-called Privacy Shield agreement does not offer sufficient protection of EU citizens’ personal data.

“The limitations on the protection of personal data arising from the domestic law of the United States on the access and use by US public authorities . . . are not circumscribed in a way that satisfies requirements that are essentially equivalent to those required under EU law,” the court said in a statement.

The ruling is a blow to the thousands of companies, including Facebook that rely on the Privacy Shield to transfer data across the Atlantic, and to the European Commission, as it unpicks an arrangement it designed with US authorities to allow companies to comply with EU data protection law.

Great ruling. It’ll be fun seeing the companies trying to find a way round it.

More than just a Twitter hack

From Om Malik:

By now, we have all heard about the takeover of the celebrity accounts and those of companies such as Apple and Uber by scammers who wanted to trick people into sending them bitcoins. There are multiple threads to this theory — Vice says that it was it might be some kind of inside job. Twitter itself says that it was a victim of social engineering. FBI is also starting an investigation. However, it is clear; this hack isn’t a joke. It can have national and international implications, as Casey Newton points out in his article for The Verge. Twitter is a significant source of dissemination of information — from weather to earthquakes to forest fires — and any disruption can cost lives.

That is why Casey is right — and collectively, we need to think about this current episode much more deeply and deliberately. Big technology platforms are now singular points of failure as much as they are single points of protection against malicious intent.

Hmmm… I’m not convinced. This particular hack was just an ingenious variation on an old scam: someone posting a link to a Bitcoin wallet with an invitation to send it some Bitcoin and receive double the amount immediately in return. You’d have to have your head examined to fall for it. The variant this time is that the scammer got into some Twitter employee’s account and used those privileges to send out the scamming tweets as if they were coming from prominent people. The big question is whether the hacker collected the DMs (Direct Messages) that those account-holders had sent to other users. If he did, then there’s big trouble ahead — and not just for the account-holders, but also for Twitter. People have been arguing for years that the private DM channel should be end-to-end encrypted, but as far as I know it isn’t.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!