A message from the cloud appreciation society

From our coastal walk on Thursday.

Quote of the Day

”An expert is someone who knows the worst mistakes that can be made in his subject and who manages to avoid them.”

- Werner Heisenberg

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Mark Knopfler & Chet Atkins playing I’ll see you in my dreams and Imagine live at the Secret Policeman’s Third Ball 1987.

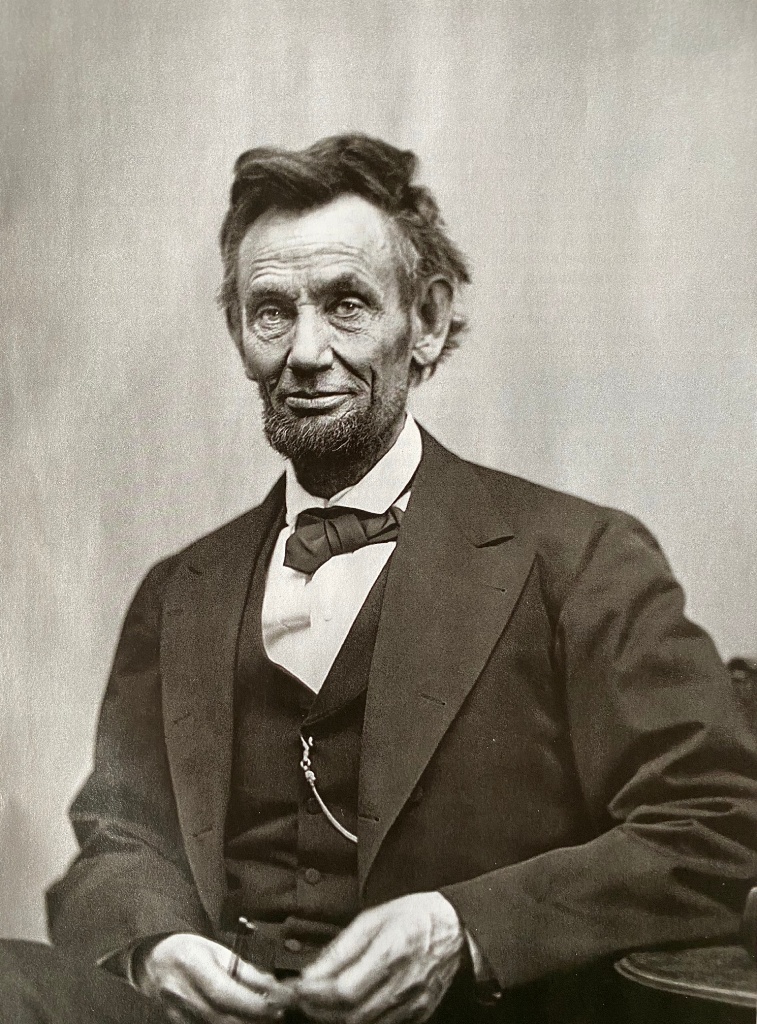

Thinking about Lincoln

I’ve been thinking about Abraham Lincoln a good deal ever since I listened to David Runciman’s unmissable podcasted talk about Max Weber’s famous lecture “Politics as a Vocation”, delivered to students in Munich in 1919. Towards the end of his talk, David identifies Lincoln as the politician who comes closest to meeting Weber’s stringent requirements for a democratic leader, and so I’ve been driven to digging out Gore Vidal’s famous historical novel about him and other stuff.

Today, I came on Adam Gopnik’s roundup essay in the New Yorker on a raft of contemporary biographies of Lincoln, which of course I dived into and found myself transfixed by this wonderful photograph of him which I’d never seen before. It’s such a revealing portrait of its subject.

Lincoln was famously ungainly and physically awkward. Gopnik retells the story of when he was President and his Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, compared him to a baboon. Asked how he could endure such an insult, Lincoln replied: “That is no insult; it is an expression of opinion; and what troubles me most about it is that Stanton said it, and Stanton is usually right.”

Gopnik’s argument is that historians’ visions of Lincoln have been shaped by their own political landscapes and cultural contexts. Which neatly explains why he has been much on our minds at the moment. And isn’t it weird — looking at the current GOP — that he was a Republican!

Ireland might yet be forced to accept that €13 billion in back tax from Apple

This is straight out of the you-couldn’t-make-it-up department.

Way back in 2016 the European Commission issued a ruling that Ireland had given Apple a “sweetheart deal” that let the company pay significantly lower taxes than other businesses. “Member States cannot give tax benefits to selected companies — this is illegal under EU state aid rules,” the EU’s antitrust Commissioner Margrethe Vestager said in 2016.

The commission ordered Apple to pay €13 billion ($14.9 billion) in back taxes to the Irish government. Needless to say, Apple disputed the decision, with CEO Tim Cook calling the judgment “total political crap.” But — here’s the startling bit — the Irish government also appealed the decision! This must be the first recorded case of a cash-strapped government facing Brexit campaigning not to receive enough dosh to run the country’s health service for a year or two.

In July this year In July, the General Court of the EU annulled the 2016 ruling on the grounds that that the commission had failed to make its case. “The commission did not succeed in showing to the requisite legal standard that there was an advantage” for Apple, they declared, and “the commission did not prove, in its alternative line of reasoning, that the contested tax rulings were the result of discretion exercised by the Irish tax authorities.”

On Friday the Commission announced that it will appeal the court’s July ruling, with Vestager saying in a statement that the court “has made a number of errors of law.”

“The General Court has repeatedly confirmed the principle that, while Member States have competence in determining their taxation laws taxation, they must do so in respect of EU law, including State aid rules,” Vestager said. “If Member States give certain multinational companies tax advantages not available to their rivals, this harms fair competition in the European Union in breach of State aid rules.”

Quite so.

A detached observer might ask why the Irish government took the line it did in this case. The short answer is that since 1958 the prime strategy of the Irish state has to carve out an economic future for a small island by being nice to giant foreign companies (especially US ones). So if it were obliged to take a more hands-off stance to these giants — even as some of them, especially Facebook and Google (both with their European HQs in Dublin) are turning toxic — then it would be changing the habits of several political lifetimes.

This one will run for a while yet.

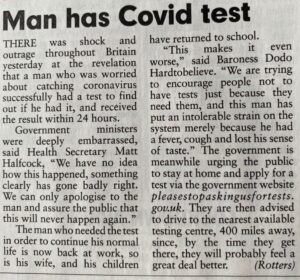

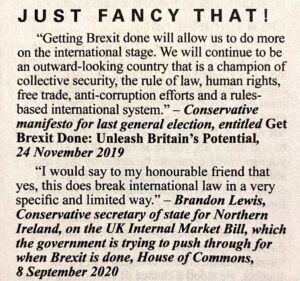

Why we need satire

From the (consistently funny) current issue of Private Eye — sometimes the only publication that keeps UK residents sane and the moment.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!