Quote of the Day

“Where there is much to learn, there of necessity will be much arguing, much writing, many opinions; for opinions in good men is but knowledge in the making.”

- Milton, Areopagatica

Yeah, but that was before social media :-(

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Here Comes The Sun – Gabriella Quevedo

How GitLab is transforming the future of online work

GitLab is a company which makes an application that enables developers to collaborate while writing and launching software. But it has no physical headquarters. Instead, it has more than 1,300 employees spread across 67 countries and nearly every time zone, all of them working either from home or (in nonpandemic times) in co-working spaces. So in contrast with most companies — which are trying to figure out how to manage remote working — it’s been doing so successfully for years.

FastCompany has an interesting piece on what the rest of us might learn from GitLab’s experience.

Research shows that talking about non-work-related things with colleagues facilitates trust, helps break down silos among departments, and makes employees more productive. At GitLab, all of this has always had to happen remotely.

The company takes these relaxed interactions so seriously that it has a specified protocol in its employee handbook, which is publicly available online in its entirety. If printed, it would span more than 7,100 pages.

The section on “Informal Communication in an All-Remote Environment” meticulously details more than three dozen ways coworkers can virtually connect beyond the basic Zoom call, from Donut Bot chats (where members of the #donut_be_strangers Slack channel are randomly paired) to Juice Box talks (for family members of employees to get to know one another). There are also international pizza parties, virtual scavenger hunts, and a shared “Team DJ Zoom Room.

But in addition to cultivating a vibrant culture of watercooler Zoom meetings over the past decade GitLab has also tackled a real problem in remote-working organisations: how to effectively induct new recruits into such a distributed organisational culture. It’s done this by setting rules for email and Slack to ensure that far-flung employees, working on different schedules around the globe, are looped in to essential messages.

To make this possible, the company has designed a workplace that makes other companies’ approach to transparency look positively opaque. At GitLab, meetings, memos, notes, and more are available to everyone within the company—and, for the most part, to everyone outside of it, too. Part of this embrace of transparency comes from the open-source ethos upon which GitLab was founded. (GitLab offers a free “community” version of its product, as well as a proprietary enterprise one.) But it’s also crucial to keeping employees in lockstep, in terms of product development and corporate culture.

GitLab raised $268 million last September at a $2.75 billion valuation and is rumored to be preparing for a direct public offering. (Its biggest competitor is GitHub, which Microsoft acquired for $7.5 billion in 2018.) As the company’s profile rises, its idiosyncratic workplace culture is attracting attention.

This is interesting. Lots of organisations could learn lessons from this. Maybe GitLab should spin out a consultancy business.

Life in the Wake of COVID-19

Lovely, moving photo essay

In April, José Collantes contracted the new coronavirus and quarantined himself in a hotel set up by the government in Santiago, Chile, away from his wife and young daughter. The 36-year-old Peruvian migrant showed only mild symptoms, and returned home in May, only to discover his wife, Silvia Cano, had also fallen ill. Silvia’s condition worsened quickly, and she was taken to a nearby hospital with pneumonia. Although they spoke on the phone, José and their 5-year-old daughter Kehity never saw Silvia again—she passed away in June, at the age of 37, due to complications from COVID-19. José found that he’d suddenly become a single parent, and felt haunted by questions about why Silvia had died and he survived.

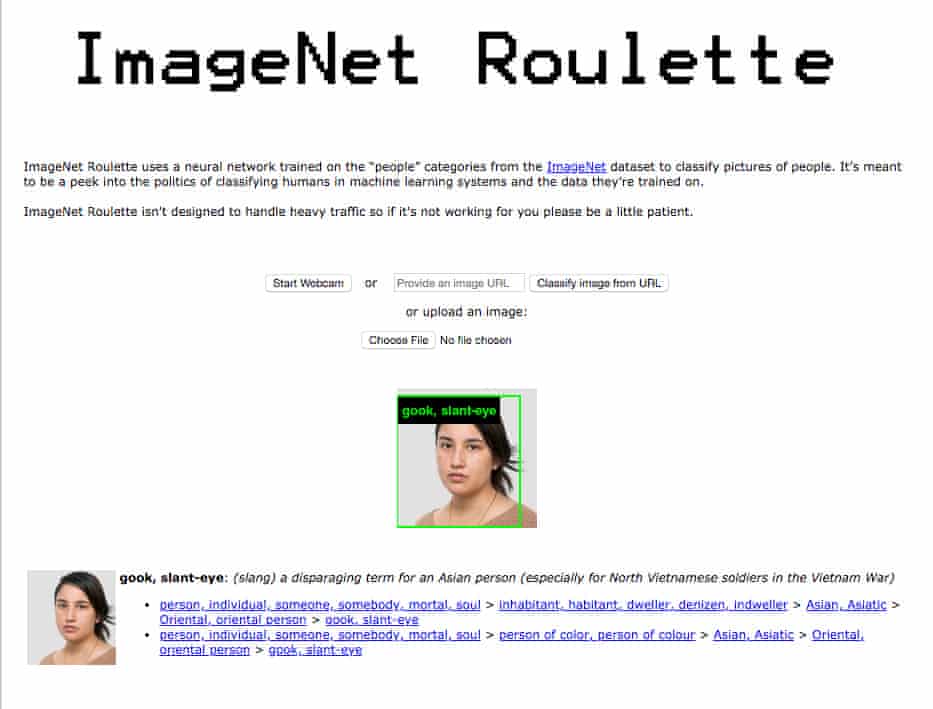

AI ethics groups are repeating one of society’s classic mistakes

It’s funny to see how the tech industry suddenly discovered ethics, a subject about which the industry’s companies were almost as ignorant as tobacco companies or soft-drinks manufacturers. Now, ‘ethics’ and ‘oversight’ boards are springing up everywhere, most of which are patently pre-emptive attempts to ward off legal regulation, and are largely engaged in ‘ethics theatre’ — much like the security-theatre that goes on in airports worldwide.

This Tech Review essay by Abhishek Gupta and Victoria Heath argues that even serious-minded ethics initiatives suffer from critical geographical blind-spots.

AI systems have repeatedly been shown to cause problems that disproportionately affect marginalized groups while benefiting a privileged few. The global AI ethics efforts under way today—of which there are dozens—aim to help everyone benefit from this technology, and to prevent it from causing harm. Generally speaking, they do this by creating guidelines and principles for developers, funders, and regulators to follow. They might, for example, recommend routine internal audits or require protections for users’ personally identifiable information.

We believe these groups are well-intentioned and are doing worthwhile work. The AI community should, indeed, agree on a set of international definitions and concepts for ethical AI. But without more geographic representation, they’ll produce a global vision for AI ethics that reflects the perspectives of people in only a few regions of the world, particularly North America and northwestern Europe.

“Those of us working in AI ethics will do more harm than good,”, Gupta and Heath argue,

if we allow the field’s lack of geographic diversity to define our own efforts. If we’re not careful, we could wind up codifying AI’s historic biases into guidelines that warp the technology for generations to come. We must start to prioritize voices from low- and middle-income countries (especially those in the “Global South”) and those from historically marginalized communities.

Advances in technology have often benefited the West while exacerbating economic inequality, political oppression, and environmental destruction elsewhere. Including non-Western countries in AI ethics is the best way to avoid repeating this pattern.

So: fewer ethics advisory jobs for Western philosophers, and more from experts from the poorer parts of the world. This will be news to the guys in Silicon Valley.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!