Category Archives: Music industry

Nostalgia isn’t a business model

On a whim, we went to see The Artist last night, and enjoyed it a lot. It’s a nicely-made, cleverly-written, amusing movie about technological transition in a media industry — the switch from silent movies to “talkies”. It stars Jean Dujardin as George Valentin, a matinee idol of the silent era who cannot come to terms with the fact that the technology has moved on, and the stunningly beautiful Bérénice Bejo as a young actress who adapts easily to talkies and becomes as big a star as Valentin once was. There are three other memorable performances: George Goodman as Al Zimmer, the boss of Kinograph Studios — an archetypal Hollywood mogul; James Cromwell as Clifton, Valentin’s faithful chauffeur; and Valentin’s entrancing dog, played by a canine named Uggie. Personally, I would have given the dog an Oscar.

Two things struck me about the film. Firstly, it took me back to Tim Wu’s book, The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires (Borzoi Books), in which he surveys the history of the great US communications industries of the 20th century. Al Zimmer is clearly a version of Adolph Zukor, the mogul who created the modern studio system by industrialising movie production and vertically integrating the business so that he controlled everything from the actors’ contracts and production budgets down to the cinemas in which the products were screened. Wu’s contention is that the history of the telephone, movie, radio and TV industries displays a common feature: they all go through a cycle, in which they start out chaotic and gloriously creative (but anarchic), until eventually a charismatic entrepreneur arrives who brings order to the chaos by offering consumers a more dependable and technologically superior product, the popularity of which enables him to capture the industry. Zukor did that for the movie business, just as — in our time — Steve Jobs did it for the music business. And in The Artist Zimmer immediately grasps the significance of audio and goes for it like an ostrich at a brass doorknob (as PG Wodehouse would have said).

The story line of the film is centred on Valentin’s obstinate refusal to accept the reality created by the new technology. It’ll never catch on, he sneers. People don’t want to hear actors talking. And here I was immediately reminded of the way print journalists reacted to the Internet — and the way academics reacted to Wikipedia. The only difference is that Valentin is rescued from his own obdurate torpor at the last minute, and learns to turn a new trick, whereas some journalists and academics would sooner die than change their minds.

But then, that’s life.

1984 wasn’t cancelled, merely postponed

One of the chapters in my new book (out on Thursday next though Amazon seems to be already selling the Kindle edition) is about the potential of computing and network technology to create systems for perfect surveillance and control. I’ve argued that the threat comes from two directions: one is the Orwellian one that we all know about; the other comes from companies like Apple and Google and Facebook. In both cases the connivance — tacit or active – of democratic governments is required. This anguished piece by Thom Holwerda suggests that the penny has dropped for him.

Here we are, at the start of 2012. Obama signed the NDAA for 2012, making it possible for American citizens to be detained indefinitely without any form of trial or due process, only because they are terrorist suspects. At the same time, we have SOPA, which, if passed, would enact a system in which websites can be taken off the web, again without any form of trial or due process, while also enabling the monitoring of internet traffic. Combine this with how the authorities labelled the Occupy movements – namely, as terrorists – and you can see where this is going.

In case all this reminds you of China and similarly totalitarian regimes, you're not alone. Even the Motion Picture Association of America, the MPAA, proudly proclaims that what works for China, Syria, Iran, and others, should work for the US. China's Great Firewall and similar filtering systems are glorified as workable solutions in what is supposed to be the free world.

The crux of the matter here is that unlike the days of yore, where repressive regimes needed elaborate networks of secret police and informants to monitor communication, all they need now is control over the software and hardware we use. Our desktops, laptops, tablets, smartphones, and all manner of devices play a role in virtually all of our communication. Think you’re in the clear when communicating face-to-face? Think again. How did you arrange the meet-up? Over the phone? The web? And what do you have in your pocket or bag, always connected to the network?

This is what [Richard] Stallman has been warning us about all these years – and most of us, including myself, never really took him seriously. However, as the world changes, the importance of the ability to check what the code in your devices is doing – by someone else in case you lack the skills – becomes increasingly apparent. If we lose the ability to check what our own computers are doing, we’re boned.

Thom also points to Cory Doctorow’s chilling talk at the Chaos Computer Congress in Berlin, entitled “The coming war on general computation,” which sets things out pretty clearly.

(Transcript here for those who are too busy to watch all the way through.)

One of the most depressing things now is the discovery that Obama seems not just clueless and passive about this stuff, but that — when push comes to shove — he really sides with the forces of darkness. If SOPA ever makes it through Congress, for example, my guess is that he will sign it. After all, as Thom points out, he signed the NDAA 2012.

Amazon’s new Cloud Drive rains on everyone’s parade

This morning’s Observer column.

“Impetuosity and audacity,” wrote Machiavelli, “often achieve what ordinary means fail to achieve.” If you doubt that, may I propose a visit to the upper echelons of Apple, Google and Sony, where steam might be observed venting from every orifice of senior executives? If you do undertake such a visit, do not under any circumstances mention the word “Amazon”.

The proximate cause of all this corporate spleen is the launch last week of Amazon’s Cloud Drive service. At first sight, it seems straightforward: it looks like a digital locker in which one may for a fee securely store one’s digital assets in the internet ‘cloud’. “Anything digital, securely stored,” runs the blurb, “available anywhere.” The first 5GB of storage is free, with more available at an annual cost of a dollar per gigabyte. Upload files to your "cloud drive", where they are stored online and from where they can be accessed by any device that you own.

So far, so innocuous. It’s not the online storage business that has Apple, Google & Co spitting feathers, but the Amazon CloudPlayer which goes along with the digital locker…

Economics of the music business

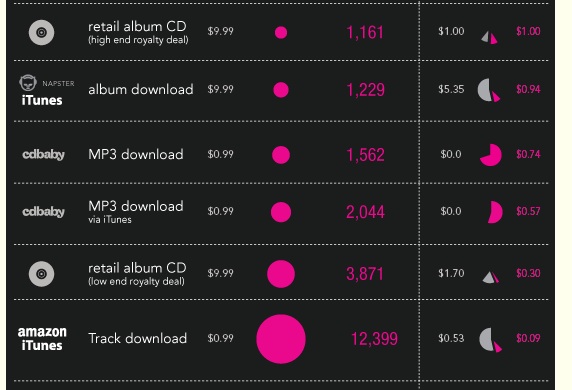

This graphic is a snapshot of a section of Ben Johncock’s ingenious and sobering visualisation of the sales in various formats a solo artist would need to achieve to earn the US minimum wage.

Ben’s point is that from the point of view of the artist the worst option of all is Spotify. But I was also struck by the asymmetry of the label vs. artist proportions (white vs purple numbers in right-hand column) on iTunes.

CORRECTION: Many thanks to all the readers who emailed to point out that the dazzling visualisation is the work of the incomparable David McCandless. The link to his graphic is here. The link was also at the bottom of Neb Johncock’s original post, but I missed it. Mea culpa, as we say in Ireland.

10 Digital Music predictions for 2011

Interesting post by Luke Lewis.

Here are the ones that struck me:

Worth reading in full. The most controversial one is his conclusion that the Spotify business model isn’t sustainable. I’m not convinced.

Thanks to Caspar for the link.

LATER: Interesting email from a reader re my comment about Spotify:

Maybe Spotify and streaming is not the future. I’ve been a paid subscriber to Spotify for over a year and have just discovered that half of my playlists and downloaded tracks have been removed owing to ECM pulling out (Naxos are rumoured to be next to go). Ironic as well over a third of my CD and LP collection is ECM and the last three CDs I have bought (within the last three months) are all ECM.

Music: better off on BitTorrent? And as for iTunes…

Fascinating TorrentFreak interview with Benn Jordan, one of the first musicians to release his stuff on BitTorrent. Excerpt:

TF: What are your thoughts on the big labels. Are they good or bad for the majority of artists?

Jordan: I have to be honest. Big labels that aren’t being innovative are little more than delusional laughing stocks at this point. Their numbers get worse and worse, and they push the artists to do dumber and dumber stunts to try and stay on top of things.

The shows and festivals they book are sponsored by 8 different alcoholic beverages and 10 different energy drinks, and they just punish their customers while validating their own demise. I’m not worried about them and neither should you. Its a dozen senior citizens trying to stop a stampede of fresh culture. Good luck boys.

TF: And what about Apple?

Jordan: Apple, love or hate their products, is fucking scary. On one hand, hats off. They’re business and marketing geniuses. On the other hand, they might single handedly be the worst thing that has happened to entertainment media in the last 3 years. The major record industry collapsing should also mean that artists are more free to do what they want.

For example, iTunes completely screwed up the track listing of my last album Arboreal. Their network is so influential that over half of the people who have bought the CD from my label now have botched track titles on their mp3 players. Apple doesn’t have ANY accessible artist support to deal with things like this.

They reject my cover art if I don’t have my name and the title in bold. If I want to sell a 30 minute long track (Louisiana Mourning, for example), they require me to split it up into a bunch of separate tracks. Their distribution system is so unorganized that artists have to pay business like Tunecore upwards of $40 per album (and annual fees) to do Apple’s job for them.

Again, its genius on the business side. But they’ve wedged themselves in so well that now, if I don’t have an album on iTunes (under their insane rules and lack of support), a large portion of my listeners simply won’t know how to put my music on their iPods/iPhones.

I know I sound preachy, but think about it, how is that any better than what existed 15 years ago? I still maintain that I’d rather have my stuff “illegally” downloaded than have to go down that path.

TF: What advise do you have for artists who consider giving away their music?

Jordan: That being a “consideration” is always funny to me. You either release it knowing it will be distributed for free or you keep it locked up on your hard drive. If the last decade has taught us anything, it is that no amount of bitching, threatening, lobbying, suing, or file protecting is going to stop information from being spread to those who want it.

How are the mighty fallen

This morning’s Observer column.

You have to feel sorry for Sony sometimes. I mean to say, there it was on Wednesday in Berlin, at the IFA consumer electronics show, launching a new music and video download service called Qriocity (it’s like “curiosity”, only it couldn’t get the domain name, I suppose) – and what happens? Steve Jobs goes on stage in San Francisco and announces that Apple is having another go at the TV download business.

And guess who gets all the media coverage?

How are the mighty fallen. I remember a time when Sony dominated the gadgetry business, when it was a synonym for elegant design and advanced functionality, when Walkmans ruled the world. It had shops in upmarket malls where young males came to drool. And now? Ask a teenager about Sony and s/he will reply: “Aren’t they the outfit that makes flat-screen TVs and DVD players and other stuff for adults?”

DeadHead memories

My Observer column on Sunday about the perceptiveness of the Grateful Dead has triggered fond memories in some readers — and stimulated some lovely emails, including this one from a colleague:

In 1972 I was one of the organisers of a big music festival in a place called Bickershaw near Wigan. The Dead were top of the bill and during contract negotiations with them, we were amazed that we had to provide a central area to accommodate anyone who wanted to record their gig. They had realised as early as 1972 that they could give away poor quality recordings, knowing that many would then go out and buy the real thing. I believe they were the largest earners amongst R&R bands for many years. I hung out with Jerry Gracia for a bit and he was very stoned but also very smart.

An interesting footnote – the main festival organiser was one Jeremy Beadle. He wasn’t famous yet but had already started to assume his annoying persona. I think he was the only person at the festival who wasn’t stoned, but he was also very smart and went on to make made lots of money.

There’s a web site for the aforementioned festival too. Gosh! Those were the days.

Post-Medium Publishing

Paul Graham, who is a terrific essayist as well as a successful entrepreneur, has a new piece on Post-Medium Publishing which has some very perceptive things to say about what print publishers are getting wrong. He concludes it thus:

I don’t know exactly what the future will look like, but I’m not too worried about it. This sort of change tends to create as many good things as it kills. Indeed, the really interesting question is not what will happen to existing forms, but what new forms will appear.

The reason I’ve been writing about existing forms is that I don’t know what new forms will appear. But though I can’t predict specific winners, I can offer a recipe for recognizing them. When you see something that’s taking advantage of new technology to give people something they want that they couldn’t have before, you’re probably looking at a winner. And when you see something that’s merely reacting to new technology in an attempt to preserve some existing source of revenue, you’re probably looking at a loser.

Yep. That’s why Napster took off: people wanted tracks but the record industry would only sell them albums, because the economics of shipping plastic disks made that mandatory. Napster enabled users to get tracks, and boy did they like it. Of course it helped that the tracks were free. But if they had been reasonably priced from the outset, illicit file-sharing would have been containable.

Thanks to Jeff Jarvis for the link.