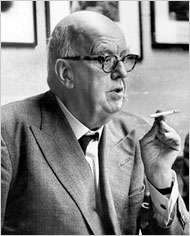

Today is the 60th anniversary of CP Snow’s celebrated Rede Lecture on the Two Cultures, which started an argument that sometimes rages still. Tim Harford has a nice essay marking the anniversary. Sample:

Snow was on to something important. His message was garbled, in fact, because he was on to several important things at once. The first is the challenge of collaboration. If anything, The Two Cultures understates that. Yes, the classicists need to work with the scientists, but the physicists also need to work with the biologists, the economists must work with the psychologists, and everyone has to work with the statisticians. And the need for collaboration between technical experts has grown over time because, as science advances and problems grow more complex, we increasingly live in a world of specialists.

The economist Benjamin Jones has been studying this issue by examining databases of patents and scientific papers. His data show that successful research now requires larger teams filled with more specialised researchers. Scientific and material progress demands complex collaboration.

Snow appreciated — in a way that many of us still do not — how profound that progress was. The scientist and writer Stephen Jay Gould once mocked Snow’s prediction that “once the trick of getting rich is known, as it now is, the world can’t survive half rich and half poor” and that division would not last to the year 2000. “One of the worst predictions ever printed,” scoffed Gould in a book published posthumously in 2003.

Had Gould checked the numbers, he would have seen that between 1960 and 2000, the proportion of people living in extreme poverty had roughly halved, and it has continued to fall sharply since then. Snow’s 40-year forecast was more accurate than Gould’s 40 years of hindsight. Even when we fancy ourselves broadly educated, as Gould did, we may not know what we don’t know. That was one of Snow’s points.

But the deepest point of all — buried a little too deep, perhaps — is a practical problem that remains as pressing today as it was in 1959: how to reconcile technical expertise with the demands of policy and politics. In short — have we really had enough of experts?

The historian Lisa Jardine highlights this sentence in Snow’s argument: “It is the traditional culture, to an extent remarkably little diminished by the emergence of the scientific one, which manages the western world.” We didn’t decide we’d had enough of experts in 2016; we made that decision long ago.

Cambridge University Press published a nice anniversary edition of the lectures a while back, with a wonderful introductory essay by Stefan Collini.

In some ways, Snow was a sad — and sometimes a ponderous — figure. I met him once. I was writing a profile of Solly Zuckerman at the time and went to see him in his office in London (he was an official in Harold Wilson’s administration). I found him to be helpful and generous with his time.