Quote of the Day

In this election there are two sides. One side believes in the rule of law, the other doesn’t. Everything else, to be settled later, once the rule-of-law is re-established.

_____________________________

My review of Andrew Marantz’s new book — Antisocial

On today’s Guardian. It’s a sobering read.

There has always been a dark undercurrent of white supremacism in some sectors of American culture. It was kept from public view for decades by the editorial gatekeepers of the old media ecosystem. But once the internet arrived, a sophisticated online culture of conspiracy theorists, racists and other malign discontents thrived in cyberspace. But it stayed below the radar until a fully paid-up conspiracy theorist won the Republican nomination. Trump’s candidacy and campaign had the effect of “mainstreaming” that which had previously been largely hidden from view. At which point, the innocent public began to see and experience what Marantz has closely observed, namely the remarkable capabilities of extremist “edgelords” to weaponise YouTube, Twitter and Facebook for destructive purposes.

One of the most depressing things about 2016 was the apparent inability of American journalism to deal with this pollution of the public sphere. In part, this was because they were crippled by their professional standards. It’s not always possible to be even-handed and honest. “The plain fact,” writes Marantz at one point, “was that the alt-right was a racist movement full of creeps and liars. If a newspaper’s house style didn’t allow its reporters to say so, then the house style was preventing its reporters from telling the truth.” Trump’s mastery of Twitter led the news agenda every day, faithfully followed by mainstream media, like beagles following a live trail. And his use of the “fake news” metaphor was masterly: a reminder of why, as Marantz points out, Lügenpresse – “lying press” – was also a favourite epithet of Joseph Goebbels.

Frank Ramsey

Frank Ramsey was a legend in Cambridge as one of the brightest young men of his time. He died tragically young (he was 26) in 1930, from an infection acquired from swimming in the river Cam. Now there’s a new biography of him by Cheryl Misak. Here’s part of her blurb about him:

The economist John Maynard Keynes identified Ramsey as a major talent when he was a mathematics student at Cambridge in the early 1920s. During his undergraduate days, Ramsey demolished Keynes’ theory of probability and C.H. Douglas’s social credit theory; made a valiant attempt at repairing Bertrand Russell’s Principia Mathematica; and translated Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, and wrote a critique of the latter alongside a critical notice of it that still stands as one of the most challenging commentaries of that difficult and influential book.

Keynes, in an impressive show of administrative skill and sleight of hand, made the 21-year-old Ramsey a fellow of King’s College at a time when only someone who had studied there could be a fellow. (Ramsey had done his degree at Trinity).

Ramsey validated Keynes’ judgment. In 1926 he was the first to figure out how to define probability subjectively and invented the expected utility that underpins much of contemporary economics.

I’d never heard of Ramsey until I came on Keynes’s essay on him in his wonderful collection, Essays in Biography, published in 1933. (One of my favourite books, btw.) Given that Keynes himself was ferociously bright, the fact that he had such a high opinion of Ramsey was what made me sit up. Here’s an extract that conveys that:

Seeing all of Frank Ramsey’s logical essays published together, we can perceive quite clearly the direction which is mind was taking. It is a remarkable example of how the young can take up the story at the point to which the previous generation had brought it a little out of breath, and then proceed forward without taking more than about a week thoroughly to digest everything which had been done up to date, and to understand with apparent ease stuff which to anyone even 10 years older seemed hopelessly difficult. One almost has to believe that Ramsay in his nursery year near Magdalene1 was unconsciously absorbing from 1903 to 1914 everything which anyone may have been saying or writing from Trinity.

(Among the people in Trinity College at the time were Bertrand Russell, A.N. Whitehead and Ludwig Wittgenstein.)

The hacking of Jeff Bezos’s phone

Interesting (but — according to other forensic experts — incomplete) technical report into his the Amazon boss’s smartphone was hacked, presumably by someone working for the Saudi Crown Prince.

_____________________________________________

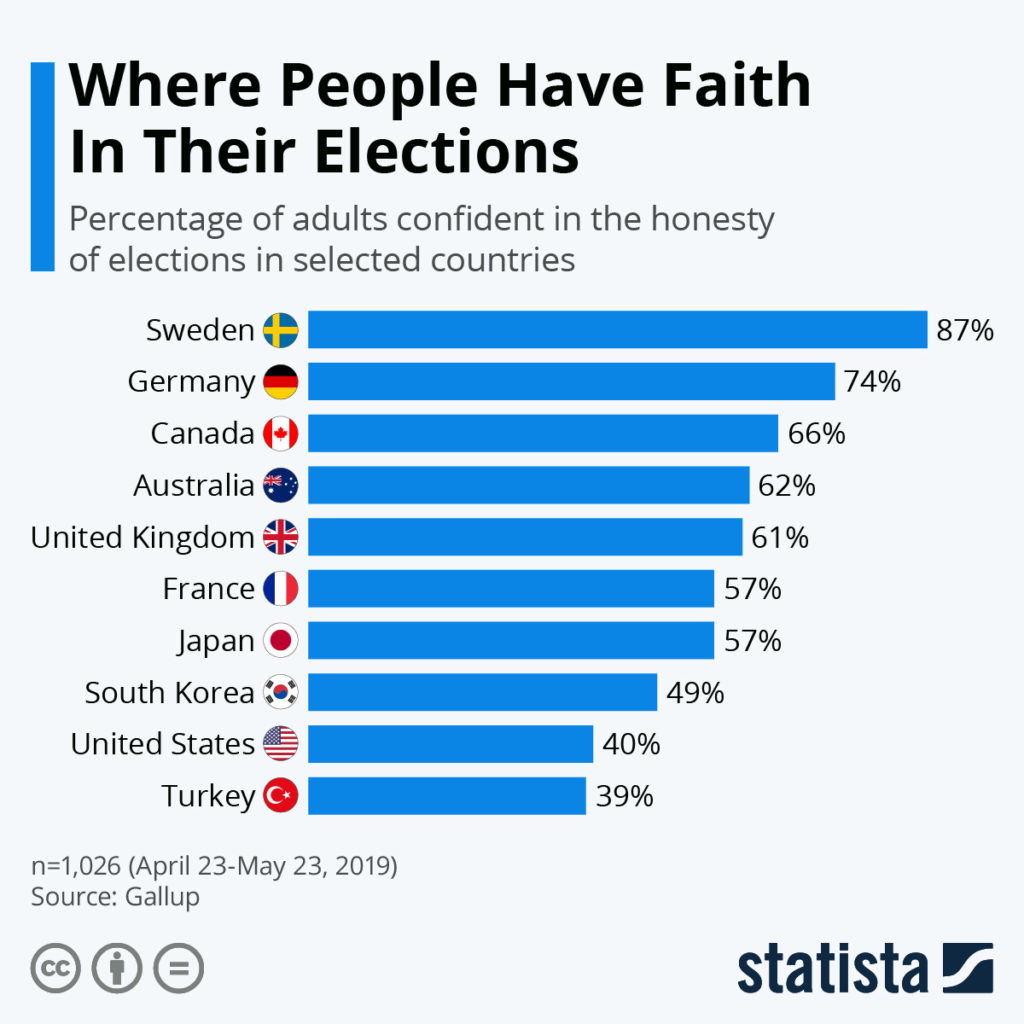

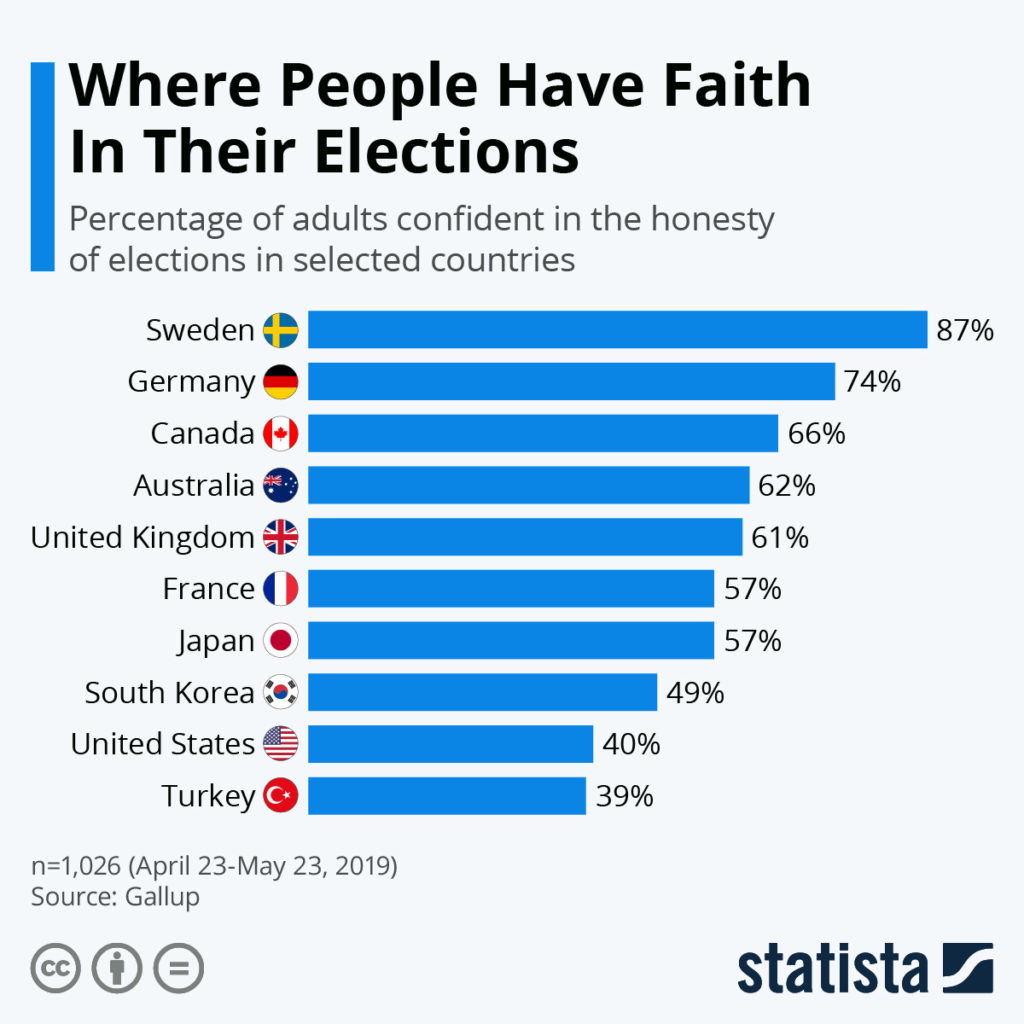

Where people have faith in their elections

The U.S. public’s confidence in elections is one of the worst of any wealthy democracy, according to a recently published Gallup poll. It found that a mere 40 percent of Americans have confidence in the honesty of their elections. As low as that figure is, distrust of elections is nothing new for the U.S. public.

The research found that a majority of Americans have had no confidence in the honesty of elections every year since 2012 with the share trusting the process at the ballot box sinking as low as 30 percent during the 2016 presidential campaign. Gallup stated that its 2019 data came at a time when eight U.S. intelligence agencies confirmed allegations of foreign interference in the 2016 presidential election and identified attempts to engage in similar activities during the midterms in 2018.

This chart shows how the U.S. compares to other developed OECD nations with the highest confidence scores recorded across Northern Europe and Finland, Norway and Sweden best-ranked.

Source

_________________________________________

David Spiegelhalter: Should We Trust Algorithms?

As the philosopher Onora O’Neill has said (O’Neill, 2013), organizations should not try to be trusted; rather they should aim to demonstrate trustworthiness, which requires honesty, competence, and reliability. This simple but powerful idea has been very influential: the revised Code of Practice for official statistics in the United Kingdom puts Trustworthiness as its first “pillar” (UK Statistics Authority, 2018).

It seems reasonable that, when confronted by an algorithm, we should expect trustworthy claims both:

-

about the system — what the developers say it can do, and how it has been evaluated, and

-

by the system — what it says about a specific case.

Terrific article