Perhaps he’s been reading Richard Susskind’s book?

Quote of the day

“I would rather have questions that can’t be answered than answers that can’t be questioned”

Richard Feynman

Facebook, ethics and us, its hapless (and hypocritical?) users

This morning’s Observer column about the Facebook ’emotional contagion’ experiment.

The arguments about whether the experiment was unethical reveal the extent to which big data is changing our regulatory landscape. Many of the activities that large-scale data analytics now make possible are undoubtedly “legal” simply because our laws are so far behind the curve. Our data-protection regimes protect specific types of personal information, but data analytics enables corporations and governments to build up very revealing information “mosaics” about individuals by assembling large numbers of the digital traces that we all leave in cyberspace. And none of those traces has legal protection at the moment.

Besides, the idea that corporations might behave ethically is as absurd as the proposition that cats should respect the rights of small mammals. Cats do what cats do: kill other creatures. Corporations do what corporations do: maximise revenues and shareholder value and stay within the law. Facebook may be on the extreme end of corporate sociopathy, but really it’s just the exception that proves the rule.

danah boyd has a typically insightful blog post about this.

She points out that there are all kinds of undiscussed contradictions in this stuff. Most if not all of the media business (off- and online) involves trying to influence people’s emotions, but we rarely talk about this. But when an online company does it, and explains why, then there’s a row.

Facebook actively alters the content you see. Most people focus on the practice of marketing, but most of what Facebook’s algorithms do involve curating content to provide you with what they think you want to see. Facebook algorithmically determines which of your friends’ posts you see. They don’t do this for marketing reasons. They do this because they want you to want to come back to the site day after day. They want you to be happy. They don’t want you to be overwhelmed. Their everyday algorithms are meant to manipulate your emotions. What factors go into this? We don’t know.

But…

Facebook is not alone in algorithmically predicting what content you wish to see. Any recommendation system or curatorial system is prioritizing some content over others. But let’s compare what we glean from this study with standard practice. Most sites, from major news media to social media, have some algorithm that shows you the content that people click on the most. This is what drives media entities to produce listicals, flashy headlines, and car crash news stories. What do you think garners more traffic – a detailed analysis of what’s happening in Syria or 29 pictures of the cutest members of the animal kingdom? Part of what media learned long ago is that fear and salacious gossip sell papers. 4chan taught us that grotesque imagery and cute kittens work too. What this means online is that stories about child abductions, dangerous islands filled with snakes, and celebrity sex tape scandals are often the most clicked on, retweeted, favorited, etc. So an entire industry has emerged to produce crappy click bait content under the banner of “news.”

Guess what? When people are surrounded by fear-mongering news media, they get anxious. They fear the wrong things. Moral panics emerge. And yet, we as a society believe that it’s totally acceptable for news media – and its click bait brethren – to manipulate people’s emotions through the headlines they produce and the content they cover. And we generally accept that algorithmic curators are perfectly well within their right to prioritize that heavily clicked content over others, regardless of the psychological toll on individuals or the society. What makes their practice different? (Other than the fact that the media wouldn’t hold itself accountable for its own manipulative practices…)

Somehow, shrugging our shoulders and saying that we promoted content because it was popular is acceptable because those actors don’t voice that their intention is to manipulate your emotions so that you keep viewing their reporting and advertisements. And it’s also acceptable to manipulate people for advertising because that’s just business. But when researchers admit that they’re trying to learn if they can manipulate people’s emotions, they’re shunned. What this suggests is that the practice is acceptable, but admitting the intention and being transparent about the process is not.

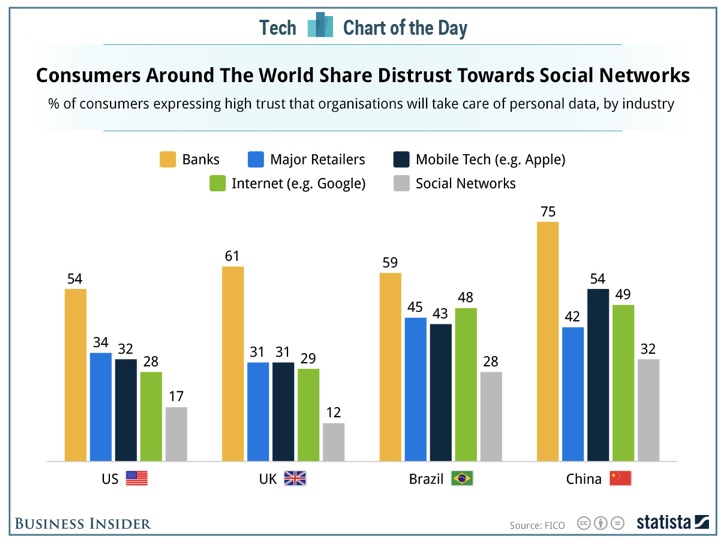

Who do you trust?

Cameron plays German roulette — and loses

If anyone needed proof of how shallow and inadequate a political leader David Cameron is, then the debacle over Jean-Claude Juncker’s appointment should be a wake-up call. We are confronted with the spectacle of a Prime Minister who has traded the economic future of his country simply in order to appease a small, fanatical minority in his own party.

You think I jest? Well, if the Tories were to win a majority in next year’s general election (and, God knows, Miliband & Co are doing their best to ensure that they do), then Cameron is committed to holding an in-out referendum on the basis of whatever deal he has managed to negotiate with the EC. The Juncker fiasco has now guaranteed that he won’t get a favourable deal from Germany et al. So he will go to the country with an unimpressive case expecting to get a “yes, we stay in” result. Guess what will happen?

This is how my colleague Andrew Rawnsley puts it in this morning’s Observer:

He has predicated the success of that enterprise almost entirely on his relationship with the German chancellor. He has piled up all his chips on Frau Merkel. He has assumed that she would help him package up a renegotiation with enough “concessions” to Britain to allow him to recommend a yes vote in a referendum.

Crucially, he has also assumed that she can deliver everyone else to a deal as well. Some of us have been warning for some time that he has staked too much on Mrs Merkel. Yes, she is a highly skilled politician. Yes, she is the most powerful woman in Europe. Yes, she would like Britain to remain within the EU. But she is subject to her own domestic pressures – she isn’t where she is without being ruthlessly protective of her interests and she will not make huge sacrifices of her own political capital just to help Britain.

There are many lessons from this debacle for the Tory leader. One is – and this he really should have guessed already – that Mrs Merkel cares more about her own political skin than she does about David Cameron’s hide. If he can’t block a poorly regarded former prime minister of a very small country who has a notorious weakness for fermented fruit in liquid form, how is David Cameron going to succeed in his self-defined and much more challenging ambition of keeping Britain in the European Union after a renegotiation of the terms of membership?

Of course there are reasons for supposing that, even in those circs, the British will shrink from pulling out, once the appalling consequences of being outside the EU sink in. Some people have pointed out that the demographics of the British electorate point in an optimistic direction, in that younger people are significantly more pro-European than older people and the anti-Europe vote is strongest among the over-60s. The only problem with that is that the old tend to be more assiduous voters than the young.

Leaving the EU would be an economic catastrophe for Britain, as well as a cultural one. Every significant British industrialist understands that. The City understands it. Every university vice-chancellor knows it. Most serious politicians know it. Every significant policy adviser in Whitehall knows it. But they are all afraid to speak out because they fear a populist backlash, fuelled by tabloid xenophobia. (Some CBI bigwigs are already nursing the wounds inflicted on them by Scot CyberNats for daring to express negative opinions about the wisdom of Scottish independence.)

The thing about Cameron is that, deep down, he’s shallow. Now we know just how shallow. Still, I guess his good friend Rebekah Brooks will have sent him a LOL message after learning of his triumph at Ypres.

Making algorithms responsible for what they do

This morning’s Observer column:

Just over a year ago, after Edward Snowden’s revelations first hit the headlines, I participated in a debate at the Frontline Club with Sir Malcolm Rifkind, the former foreign secretary who is now MP for Kensington and Chelsea and chairman of the intelligence and security committee. Rifkind is a Scottish lawyer straight out of central casting: urbane, witty, courteous and very smart. He’s good on his feet and a master of repartee. He’s the kind of guy you would be happy to have to dinner. His only drawback is that everything he knows about information technology could be written on the back of a postage stamp in 96-point Helvetica bold…

So phone hacking was just a scandal, not a crisis

Regular readers will know how useful I find David Runciman’s distinction between scandals and crises. (Scandals happen all the time, cause a lot of fuss and result in no fundamental change. Crises do trigger substantive change.) This piece by Michael Wolff, a Murdoch biographer and general-purpose media watcher, in which he reflects on the outcome of the London trial of some Murdoch lieutenants, confirms my gloomy conjecture: that the phone-hacking business was just a scandal.

The campaign’s most potent scare symbol was the disgraced Brooks, and a story line that had her using her paper and closeness to the Murdoch family to achieve vast influence in the British government. But Brooks now emerges from the nine-month trial as something more like a martyr, herself the victim of a merciless press, ever hounded by political enemies. (With special spite, her husband, who was also acquitted, was put on trial with her for hiding computers — containing, instead of evidence, his porn collection.)

But there was a conviction — one that quite nicely serves Murdoch’s purposes. Andy Coulson, former editor of Murdoch’s weekly scandal sheet, News of the World — which closed in the wake of the hacking revelations — was the one person convicted of phone hacking in the trial. Coulson had gone on to become Prime Minister David Cameron’s press secretary. Murdoch can now maintain what he has always maintained: It was disloyal midlevel lieutenants who hacked, not anyone close to him. What’s more, Coulson becomes Cameron’s problem for hiring a now-convicted felon. Murdoch has long felt it was a wishy-washy Cameron who let the hacking investigation grow and vowed his revenge. Now he has it.

The 83-year-old Murdoch’s difficulties in London aren’t quite finished. There are ongoing hearings at which he is scheduled to testify and continuing regulatory threats against his businesses. But now the `prima facie case is gone. In a sense, it is a reset. It’s back to lots of people hating Murdoch and lots of people eager to be in his favor and do his bidding.

Nothing changes. There will be no substantive change in the way the British tabloid media operate. So it was a scandal, not a crisis.

As Peter Wilby puts it in the New Statesman:

As for hoping that newspapers will repent of their sins and now accept the royal charter that followed the Leveson inquiry, forget it. “Great day for red tops”, proclaimed the Sun, celebrating Brooks’s acquittal and treating Coulson’s conviction as a mere sideshow (a “rogue editor”, perhaps). “The Guardian, the BBC and Independent will be in mourning today,” wrote its associate editor Trevor Kavanagh. “Sanctimonious actors like Hugh Grant and Steve Coogan will be deliciously Hacked Off. We have . . . taken a tentative step back towards a genuinely free press.” Murdoch’s Times judged that Brooks’s acquittal “shows that a rush to implement a draconian regime to curb a free press was a disaster”. The Daily Mail had a leader on “the futility of Leveson”.

As the press is well aware, public outrage over hacking has long passed its peak. People don’t like the tabloids and they don’t like politicians getting too close to them. They want – or say they want – stricter controls on newspapers. But in the pollsters’ jargon, the issue has “low salience”. To most, the subject just isn’t important enough to change either their vote or their buying and surfing habits in the news market. The press can continue on its merry way.

Yep. But it ought still to be a crisis for the Prime Minister, who cheerfully employed Coulson as his spinmeister despite being explicitly warned about his background. But my hunch is that Cameron is already in such deep trouble (much of it of his own making — see his fatuous campaign to prevent Jean-Claude Juncker becoming EC President) that the Coulson debacle comes relatively low down in the list.

Neoliberalism’s revolving door

Well, guess what? The former Head of the NSA has found a lucrative retirement deal.

As the four-star general in charge of U.S. digital defenses, Keith Alexander warned repeatedly that the financial industry was among the likely targets of a major attack. Now he’s selling the message directly to the banks.

Joining a crowded field of cyber-consultants, the former National Security Agency chief is pitching his services for as much as $1 million a month. The audience is receptive: Under pressure from regulators, lawmakers and their customers, financial firms are pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into barriers against digital assaults.

Alexander, who retired in March from his dual role as head of the NSA and the U.S. Cyber Command, has since met with the largest banking trade groups, stressing the threat from state-sponsored attacks bent on data destruction as well as hackers interested in stealing information or money.

“It would be devastating if one of our major banks was hit, because they’re so interconnected,” Alexander said in an interview.

Nice work if you can get it. First of all you use your position in the state bureaucracy to scare the shit out of banks. Then you pitch your services as the guy who can help them escape Nemesis.

Quote of the day

“In times of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.”

George Orwell

A borderless world?

One of my mantras is that for the first 20 years of its existence (up to 1993) cyberspace was effectively a parallel universe to what John Perry Barlow called ‘Meatspace’ (aka the real world). The two universes had very little to do with one another, and were radically different in all kinds of ways. But from 1993 (when Andreessen and Bina released Mosaic, the first big web browser) onwards, the two universes began to merge, which led to the world we have now — a blended universe which has the affordances of both cyberspace and Meatspace. This is why it no longer makes sense to distinguish (as politicians still do sometimes) between the Internet and the “real world”. And it’s also why we are having so much trouble dealing with a universe in which the perils of normal life are turbocharged by the affordances of digital technology.

This morning, I came on a really interesting illustration of this. It’s about how Google Maps deal with areas of the world where there are border disputes. Turns out that there are 32 countries in the world for which Google regards the border issue as problematic. And it has adopted a typical Google approach to the problem: the borders drawn on Google’s base map of a contested area will look different depending on where in the world you happen to be viewing them from.

An example: the borders of Arunachal Pradesh, an area administered by India but claimed as a part of Tibet by China. The region is shown as part of India when viewed from an Indian IP address, as part of China when viewed from China, and as distinct from both countries when viewed from the US.

There’s a nice animation in the piece. Worth checking out.