Walking by a clear running stream this afternoon, we came on this beautiful carpet of star-shaped plants. No idea what it is, but it was really striking.

Quote of the Day

I had a lovely email from a friend about last Friday’s “Quote of the Day” (cricket commentator Brian Johnson’s immortal remark: “The bowler’s Holding, the batsman’s Willey”) It reminded him, he wrote,

of the story about Harry Caray, a legendary American baseball announcer. Caray was calling a Chicago Cubs game on TV in the mid 1980’s. Baseball is a slow game so the cameramen were often looking for something interesting going on in the crowd. At several times during the game, the broadcast showed a particular couple in the stands making out. Finally, towards the end of the game, Caray says, “Folks, I think I figured it out. He kisses her on the strikes and she kisses him on the balls!”

Many thanks to Hap for that knockout quote.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Alfred Brendel – Schubert, Klavierstücke D. 946 No. 2 in E Flat

Finally US politicians are taking the fight to the tech giants

This morning’s Observer column

On Tuesday evening, a large (449-page) pdf landed in my inbox. It’s the majority report of the US House of Representatives judiciary committee’s subcommittee on antitrust, commercial and administrative law and it makes ideal bedside reading material for only two classes of person: competition lawyers and newspaper columnists. But even if it’s unlikely to be a bestseller, its publication is still a landmark event because it marks the first concerted (and properly resourced) critical interrogation of a new group of unaccountable powers that is roaming loose in our democracies: tech companies. Its guiding spirit was something said by the great Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis many moons ago: “We must make our choice. We may have democracy or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we cannot have both.”

Only four tech companies were targeted – Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google. How Microsoft escaped scrutiny is a mystery (to me anyway); perhaps it’s because that company had its day in court long ago and survived to become the handmaiden of governments and organisations everywhere and is therefore part of the ruling establishment.

The inquiry that led to the report started in 2019 as an investigation into the state of competition online. It had three aims: “1) to document competition problems in digital markets; 2) examine whether dominant firms are engaging in anticompetitive conduct; and 3) assess whether existing antitrust laws, competition policies and current enforcement levels are adequate to address these issues.” Crudely summarised, its conclusions are…

Good news for Glassholes

Wearable tech has never been so fashionable. Meet Spectacles 3 from Snap Inc. Capture your world in 3D with two HD Cameras and four built-in mics, which store up to 100 3D videos or 1,200 3D photos. Photos and videos wirelessly sync to your phone, where you can edit and transform then with a new suite of 3D effects on Snapchat. Recharge Spectacles 3 on the go with the included charging case.

Think of it as DIY sousveillance.

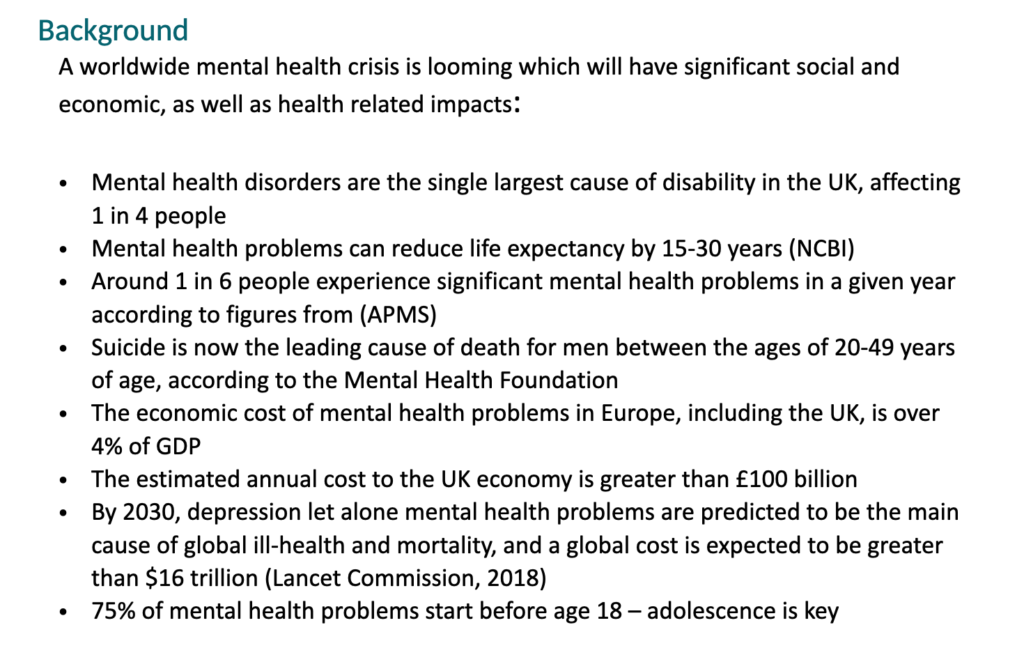

The looming mental health crisis

This is a slide from one of the most alarming presentations I’ve been to in a long time. It’s worth reading carefully. In particular, note the bullet points for life expectancy, male suicide rates, the estimated cost to the economy and the fact that three-quarters of mental health problems start before the age of 18.

Cambridge University is setting up an Institute for Mental Wellbeing, and the presentation was giving some background information on the new institute and the justifications for it.

Of course, like most people, I’ve been aware of a degree of public concern about mental health — concern which has been greatly amplified by the Coronavirus and associated lockdowns, job losses, precarity and other sources of stress. But since it’s not my field I’m ashamed to say that I had relegated discussions about it to the status of depressing background noise. I had absolutely no idea of the scale of the crisis until the meeting last Monday when the presentation was given.

Over the years some of my friends and family members have suffered from depression, anxiety and other psychological conditions, and I supported one of them through three terrible bouts, but until now I’d always thought of these as relatively rare misfortunes rather than as conditions that afflict millions of people.

How wrong can you be?

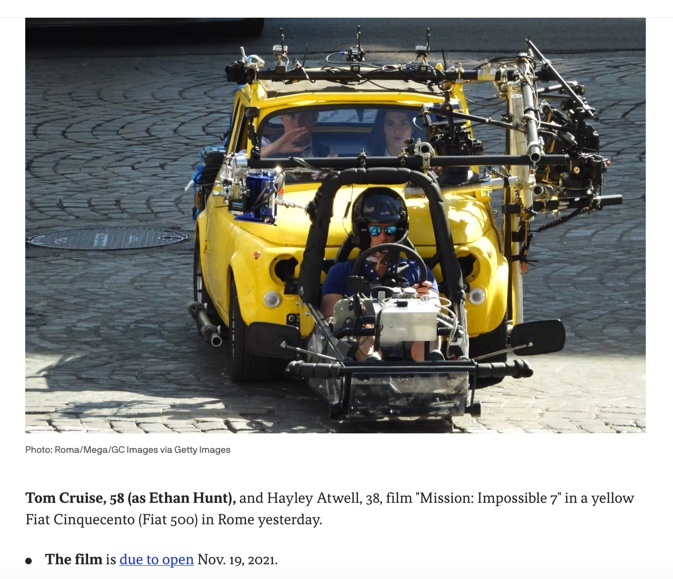

How to film a conversation in a yellow Fiat Quinquecento

From Axios

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!