Get your t-shirt now!

From some genius on Twitter.

Quote of the Day

Social media has given new meaning to “the last post”. Many victims of Covid-19 live on through their final public words, the the Detroit bus driver Jason Hargrove, who died 11 days after recording a Facebook video scolding a woman for coughing on his bus without covering her mouth.”

- Simon Kuper, Financial Times, May 23/24, 2020.

How the ‘Plandemic’ conspiracy theory took hold

This morning’s Observer column:

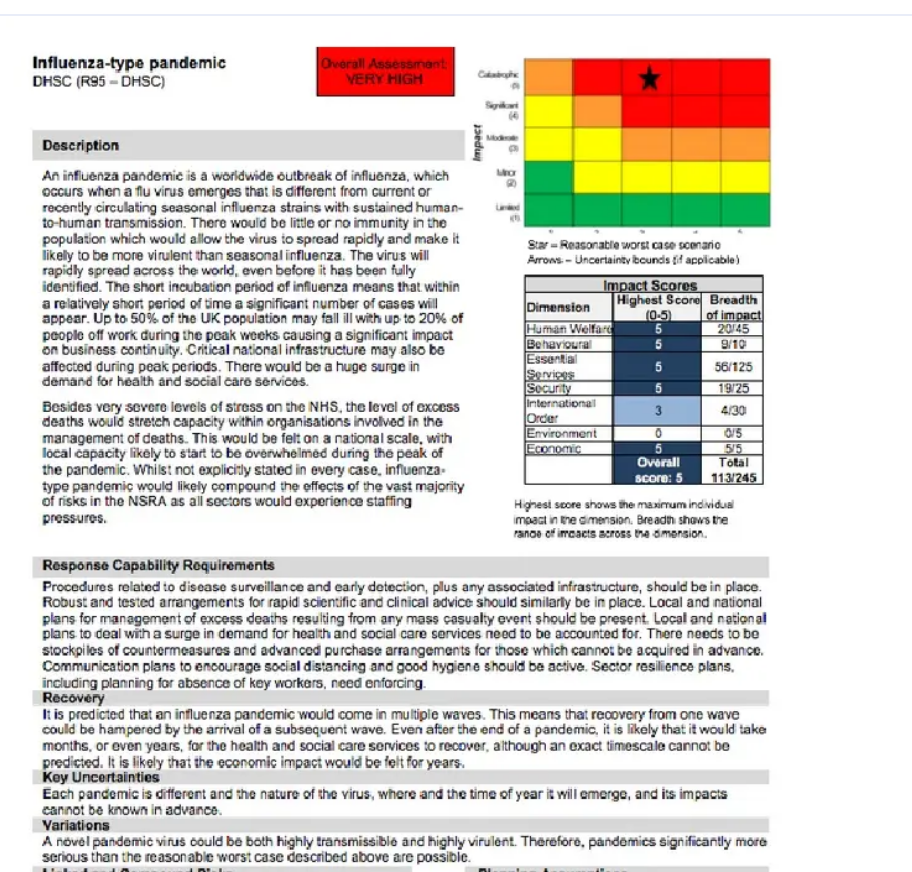

To have one viral sensation, Oscar Wilde might have said, is unfortunate. But to have two smacks of carelessness. And that’s what we have. The first is Covid-19, about which much printer’s ink has already been spilled. The second is Plandemic, a 26-minute “documentary” video featuring Dr Judy Mikovits, a former research scientist and inveterate conspiracy theorist who blames the coronavirus outbreak on big pharma, Bill Gates and the World Health Organization. She also claims that the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (which is headed by Dr Anthony Fauci) buried her research showing vaccines weaken people’s immune systems and made them more vulnerable to Covid-19. Just to round off the accusations, Mikovits claims that wearing masks is dangerous because it “literally activates your own virus”. And, if proof were needed that the pharma-Gates-scientific-elite cabal were out to get her, the leading journal Science in 2011 retracted a paper by her on a supposed link between a retrovirus and chronic fatigue syndrome that it had accepted in 2009.

The video went online on 4 May when its maker, Mikki Willis, a hitherto little-known film producer, posted it to Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo and a separate website set up to share the video…

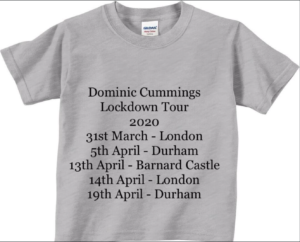

A song for Dominic Cummings

This is so clever and witty. As accomplished in its way as anything Noel Coward ever wrote.

Dr Doom explains

Nouriel Roubini is not everybody’s cup of tea, but he saw the 2008 banking crisis coming and he doesn’t see many good outcomes for the aftermath of Covid-19.

New York magazine has an interesting interview with him. Here’s the bit that really interested me:

Q: Some Trumpian nationalists and labor-aligned progressives might see an upside in your prediction that America is going to bring manufacturing back “onshore.” But you insist that ordinary Americans will suffer from the downsides of reshoring (higher consumer prices) without enjoying the ostensible benefits (more job opportunities and higher wages). In your telling, onshoring won’t actually bring back jobs, only accelerate automation. And then, again with automation, you insist that Americans will suffer from the downside (unemployment, lower wages from competition with robots) but enjoy none of the upside from the productivity gains that robotization will ostensibly produce. So, what do you say to someone who looks at your forecast and decides that you are indeed “Dr. Doom” — not a realist, as you claim to be, but a pessimist, who ignores the bright side of every subject?

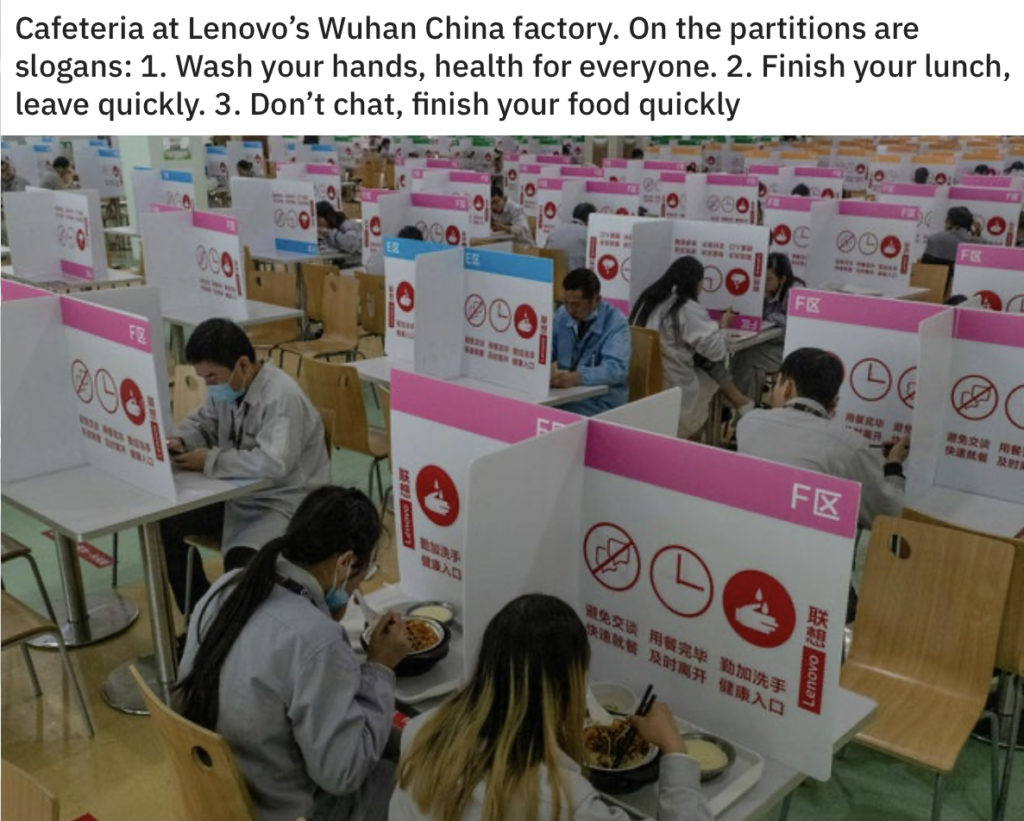

Roubini: When you reshore, you are moving production from regions of the world like China, and other parts of Asia, that have low labor costs, to parts of the world like the U.S. and Europe that have higher labor costs. That is a fact. How is the corporate sector going respond to that? It’s going to respond by replacing labor with robots, automation, and AI.

I was recently in South Korea. I met the head of Hyundai, the third-largest automaker in the world. He told me that tomorrow, they could convert their factories to run with all robots and no workers. Why don’t they do it? Because they have unions that are powerful. In Korea, you cannot fire these workers, they have lifetime employment.

But suppose you take production from a labor-intensive factory in China — in any industry — and move it into a brand-new factory in the United States. You don’t have any legacy workers, any entrenched union. You are States. You don’t have any legacy workers, any entrenched union. You are going to design that factory to use as few workers as you can. Any new factory in the U.S. is going to be capital-intensive and labor-saving. It’s been happening for the last ten years and it’s going to happen more when we reshore. So reshoring means increasing production in the United States but not increasing employment. Yes, there will be productivity increases. And the profits of those firms that relocate production may be slightly higher than they were in China (though that isn’t certain since automation requires a lot of expensive capital investment).

But you’re not going to get many jobs. The factory of the future is going to be one person manning 1,000 robots and a second person cleaning the floor. And eventually the guy cleaning the floor is going to be replaced by a Roomba because a Roomba doesn’t ask for benefits or bathroom breaks or get sick and can work 24-7.

The fundamental problem today is that people think there is a correlation between what’s good for Wall Street and what’s good for Main Street. That wasn’t even true during the global financial crisis when we were saying, “We’ve got to bail out Wall Street because if we don’t, Main Street is going to collapse.” How did Wall Street react to the crisis? They fired workers. And when they rehired them, they were all gig workers, contractors, freelancers, and so on. That’s what happened last time. This time is going to be more of the same. Thirty-five to 40 million people have already been fired. When they start slowly rehiring some of them (not all of them), those workers are going to get part-time jobs, without benefits, without high wages. That’s the only way for the corporates to survive. Because they’re so highly leveraged today, they’re going to need to cut costs, and the first cost you cut is labor. But of course, your labor cost is my consumption. So in an equilibrium where everyone’s slashing labor costs, households are going to have less income. And they’re going to save more to protect themselves from another coronavirus crisis. And so consumption is going to be weak. That’s why you get the U-shaped recovery.

There’s a conflict between workers and capital. For a decade, workers have been screwed. Now, they’re going to be screwed more. There’s a conflict between small business and large business.

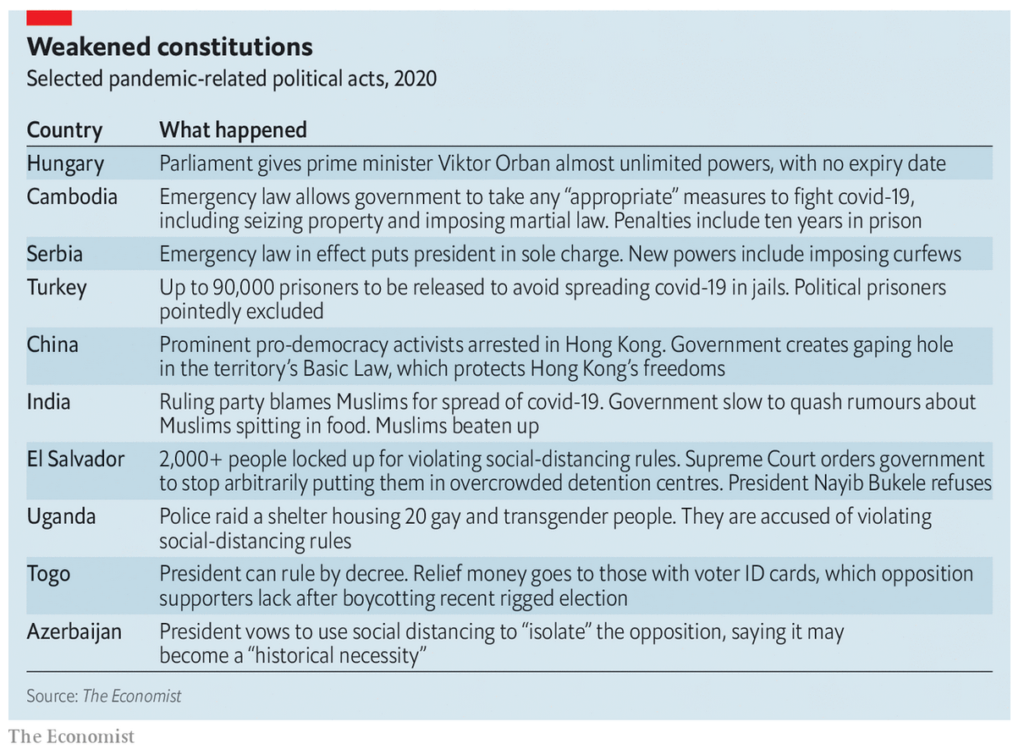

And I thought I was enraged by the current UK government…

Well, AL Kennedy is even more infuriated — see her piece in today’s Observer For example:

For a few weeks I had red eyes, a strangled cough, an invisible shovel repeatedly hitting my head and something I visualised as a tiny rabbit kicking about in my chest. But I’m not dead, thanks to austerity and all those thought experiments, that’s now a wonderful luxury, an unlooked-for plus in British life. I locked myself away, just to be sure I didn’t share the plague (sorry, Dom) and I’m OK now. I function. Or maybe I was never ill, because any prolonged reflection upon our national circumstances produces identical symptoms. I suffer from fury. I beg your pardon, The Fury. Or, indeed, THE FURY.

I mean, it’s not just anger any more, is it? It’s not any kind of emotion on a familiar human scale, not after all this. Not after the tens of thousands of avoidable deaths. Not after the nurses, teachers, doctors, bus drivers, carers, checkout staff, warehouse staff – the whole army of the useful now declared expendable. Not after people who know their jobs may kill them, may send them home infected, but they go to work anyway to keep everything running, to save us, and still they don’t get adequate pay, or equipment, or even respect. Not after our leaders always have time for racism and PR, but never for even the level of planning you’d put into a sandwich. Not after millions of us have lain awake, just hoping the people we love won’t die. Not after the drowning on dry land alone, after the mourning. Not after the Brexit cult’s insistence that no-deal Brexit must still be imposed, so hop into the wood-chipper, everyone still standing. Not after Stay Alert.

We’re quiet now – we’re trying to save each other, staying home, not forming crowds, thinking, planning. But un-isolated life will eventually recommence. We’ll remember our wounds. We’ll remember who helped and who harmed. And, pardon my language, but our government is fucking terrified of what happens then.

Yep.

That Larry Summers interview

Terrific interview with the former US Treasury Secretary and Harvard President. Long read, but mostly worth it.

Some highlights

On US-China relations…

we need to craft a relationship with China from the principles of mutual respect and strategic reassurance, with rather less of the feigned affection that there has been in the past. We are not partners. We are not really friends. We are entities that find ourselves on the same small lifeboat in turbulent waters a long way from shore. We need to be pulling in unison if things are to work for either of us. If we can respect each other’s roles, respect our very substantial differences, confine our spheres of negotiation to those areas that are most important for cooperation, and represent the most fundamental interests of our societies, we can have a more successful co-evolution that we have had in recent years.

On globalisation…

We have done too much management of globalization for the benefit of those in Davos, and too little for the benefit of those in Detroit or Dusseldorf. Over the last two decades, better intellectual property protection for Mickey Mouse and Hollywood movies has been an A level economic issue. Better global tax cooperation, so that tech companies’ profits do not locate themselves in cyberspace and entirely escape taxation, has been a B-level issue. Achieving better market access for derivatives dealers has been an A-level global economic issue, while assuring that bank secrecy does not permit large-scale money laundering has been a B-level economic cooperation issue. The protection of foreign investors’ property rights has been an A-level issue, and the maintenance of worker standards, or the avoidance of unfair competition through exchange rate depreciation, has been a B-level issue. And ultimately, that has all estranged the elite from those they aspire to lead.

Someone put it to me this way: First, we said that you are going to lose your job, but it was okay because when you got your new one, you were going to have higher wages thanks to lower prices because of international trade. Then we said that your company was going to move your job overseas, but it was really necessary because if we didn’t do that, then your company was going to be less competitive. Now we’re saying that we have to cut the taxes on those companies and cut the calculus class from your kid’s high school, because otherwise we won’t be able to attract companies to the United States, and you have to pay higher taxes and live with fewer services. At a certain point, people say, “This whole global thing doesn’t work for me,” and they have a point.

On regulation…

So the case for regulation is not to be anti-business. Regulation needs to be supported because it enables the vast majority of businesses who want to do right by society to do so and still be able to compete. That’s how the case for regulation needs to be framed. We should not be waging jihad against business. We should be waging jihad against those who put profit ahead of every other value in the society.We should not be waging jihad against business. We should be waging jihad against those who put profit ahead of every other value in the society. And that’s where in the emphasis on profit, we have gone a bit awry.

On tax and taxation policy…

The single easiest answer is that we could raise well over a trillion dollars over the next decade by simply enforcing the tax law that we have against people with high incomes. Natasha Sarin and I made this case and generated a revenue estimate some time ago. If we just restored the IRS to its previous size, judged relatively to the economy; if we moved past the massive injustice represented by the fact that you’re more likely to get audited if you receive the earned income tax credit (EITC) than if you earn $300,000 a year or more; if we made plausible use of information technology and the IRS got to where the credit card companies were 20 years ago, in terms of information technology-matching; and if we required of those who make shelter investments the kind of regular reporting that we require of cleaning women, we would raise, by my estimate, over a trillion dollars. Former IRS Commissioner Charles Rossotti, who knows more about it than I do, thinks the figure is closer to $2 trillion. That’s where we should start.

Over time I think we are going to need a larger public sector in the United States to deal with the challenges of a more complex world: an aging society, more inequality that requires mitigation, and a huge change in the relative price of the things the public sector buys, like healthcare and education. We’re going to need more revenue, beyond the unsustainable borrowing that we’re engaged in now. But the first way to get it is enforcing the law we have, which will raise substantial revenue progressively and in ways that will actually promote economic efficiency.

On raising the minimum wage and Universal Basic Income (UBI)…

I do support raising the minimum wage. It’s a matter of balance. I don’t think the minimum wage was doing any significant damage in terms of causing unemployment when Ronald Reagan was president, and the federal minimum wage is now substantially lower, after adjusting for inflation, than it was at that time. I believe raising the minimum wage would help a lot of people who are in substantial need.

I’m not enthusiastic about a universal basic income because the fact that it is so poorly targeted, precisely because of its universality, mean that it will either be prohibitively expensively or will not provide adequate benefits to the poor. Imagine a universal basic income could pay $10,000 per person—that would require nearly a doubling in the federal budget, or more than a doubling in federal tax collection, in order to finance it. That doesn’t seem to me to be remotely tenable. If you make it inexpensive, then you’re not going to be doing very much to help poor people.

On where he disagrees with Keynes’s 1930 essay on “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren”…

There’s a lot of empirical evidence since Keynes wrote, and for every non-employed middle-aged man who’s learning to play the harp or to appreciate the Impressionists, there are a hundred who are drinking beer, playing video games, and watching 10 hours of TV a day.

Great stuff. The only thing the US now needs is a President who isn’t a toddler.

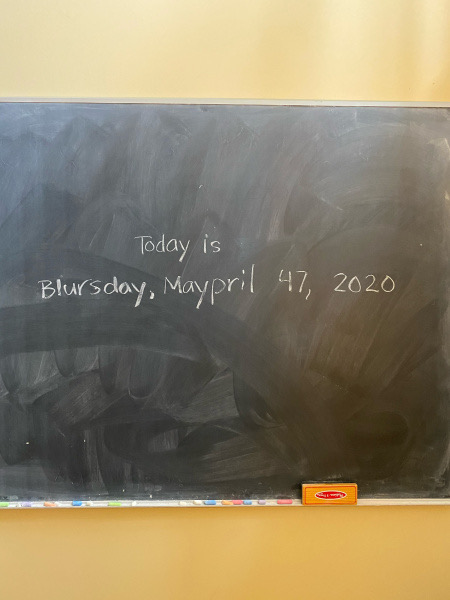

Quarantine diary — Day 64

Errata The author of Universal Man: the seven lives of John Maynard Keynes mentioned in yesterday’s Diary is Richard (not Rupert) Davenport-Hines. Many thanks to Gordon Johnson for alerting me to the error.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if your decide that your inbox is full enough already!