Soho, London.

Quote of the Day

“A family with the wrong members in control — that, perhaps, is as near as one can come to describing England in a phrase.”

- George Orwell, 1941, in The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Bach | Toccata and Fugue, BWV 565 | Edson Lopes

Thanks to Ross Anderson for suggesting it.

Gatekeepers redux?

Ben Smith (who writes about media for the New York Times) has an interesting piece about how Trump’s associates tried to plant a phoney scandal story about Joe Biden on the Wall Street Journal, and how the Journal didn’t take the bait. It’s an interesting story in itself, but it’s also about a larger shift in the American media ecosystem which suggests that maybe the editorial gatekeepers of the pre-Internet ecosystem still have some clout.

It has been a disorienting couple of decades, after all. It all began when The Drudge Report, Gawker and the blogs started telling you what stodgy old newspapers and television networks wouldn’t. Then social media brought floods of content pouring over the old barricades.

By 2015, the old gatekeepers had entered a kind of crisis of confidence, believing they couldn’t control the online news cycle any better than King Canute could control the tides. Television networks all but let Donald Trump take over as executive producer that summer and fall. In October 2016, Julian Assange and James Comey seemed to drive the news cycle more than the major news organizations. Many figures in old media and new bought into the idea that in the new world, readers would find the information they wanted to read — and therefore, decisions by editors and producers, about whether to cover something and how much attention to give it, didn’t mean much.

But the last two weeks have proved the opposite: that the old gatekeepers, like The Journal, can still control the agenda. It turns out there is a big difference between WikiLeaks and establishment media coverage of WikiLeaks, a difference between a Trump tweet and an article about it, even between an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal suggesting Joe Biden had done bad things, and a news article that didn’t reach that conclusion.

Interesting throughout.

College Application Essay Prompts For the 2020-2021 Cycle

By Eric Shan in McSweeney’s.

1 Write about a personal challenge you have recently faced and how it has shaped who you are today. While we would prefer you write about something other than the pandemic, we are resigned to the fact that you will probably write about the pandemic. Please just avoid using the word “unprecedented.”

2 Why do you want to attend our university? This is the only year we would actually believe you if you wrote, “I like your rural environment, secluded from the rest of humanity.”

and then all the way down to…

8 Which opportunities would you take advantage of while on campus (i.e., in your childhood bedroom)? Please visit our redesigned student website to browse extracurricular activities like tutoring local students but on Zoom, performing a capella but on Zoom, and playing intramural frisbee but on Zoom.

9 Who inspires you? Is it our university president, who instituted mass layoffs and a hiring freeze before increasing his own salary by 35%?

10 At the end of the day, what’s really the point of doing any of this anyway?

The App Store Debate: A Story of Ecosystems

Steven Sinofsky was at one time a very senior Microsoft executive — responsible for the development and marketing of Windows, Internet Explorer, and online services such as Outlook.com and SkyDrive. He left Microsoft in 2012 and is now a board partner at Andreessen Horowitz, the prominent venture capital firm. He writes a fascinating blog in which he occasionally picks up a topic that interests him and in the process reveals an astonishing depth of knowledge about the tech industry. (He also seems to have an encyclopedic knowledge of the Japanese camera industry.)

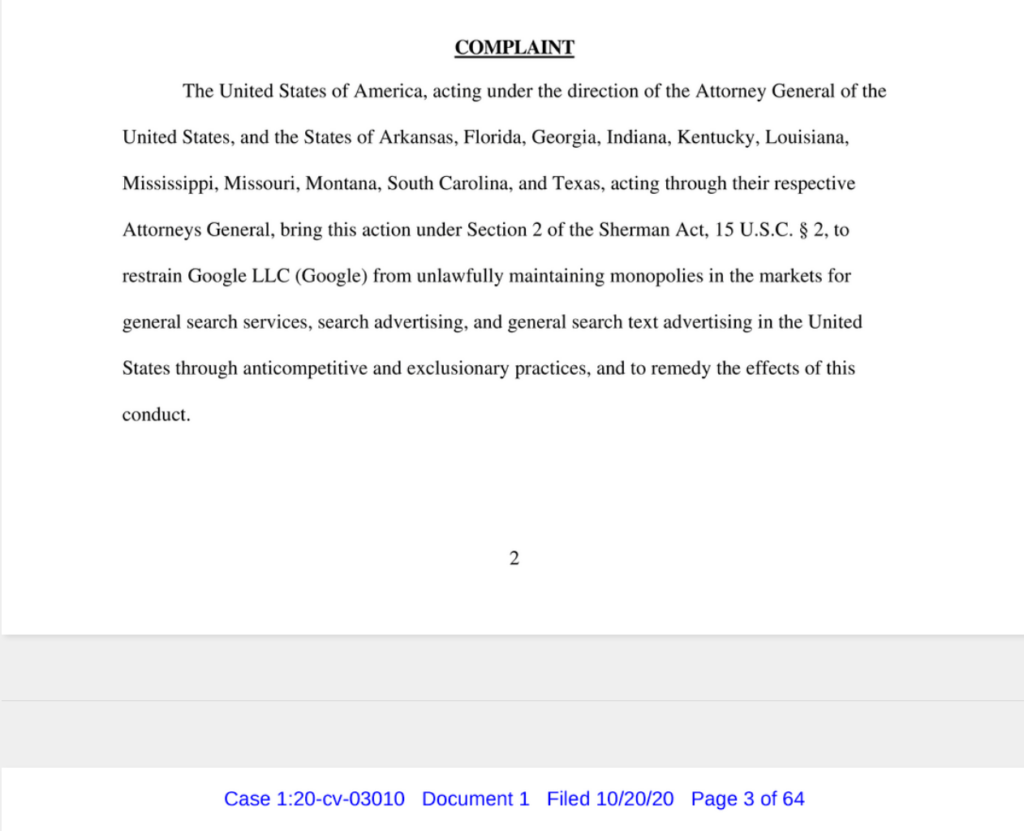

He’s just published the latest of his deep dives, triggered by the analogies being drawn between the current DoJ antitrust suit against Google and the 1998 DoJ prosecution of Microsoft, about which Sinofsky probably knows more than almost anyone. This is a VERY long read, and not for anyone who isn’t interested in the history of the PC industry, but it’s also a startling reminder of how complicated this stuff can get. If you never used MS-DOS or don’t remember Sony Vaio laptops, then this isn’t for you. If, on the other hand, you have experienced these products and that period in the tech industry’s evolution, it’s pure bliss.

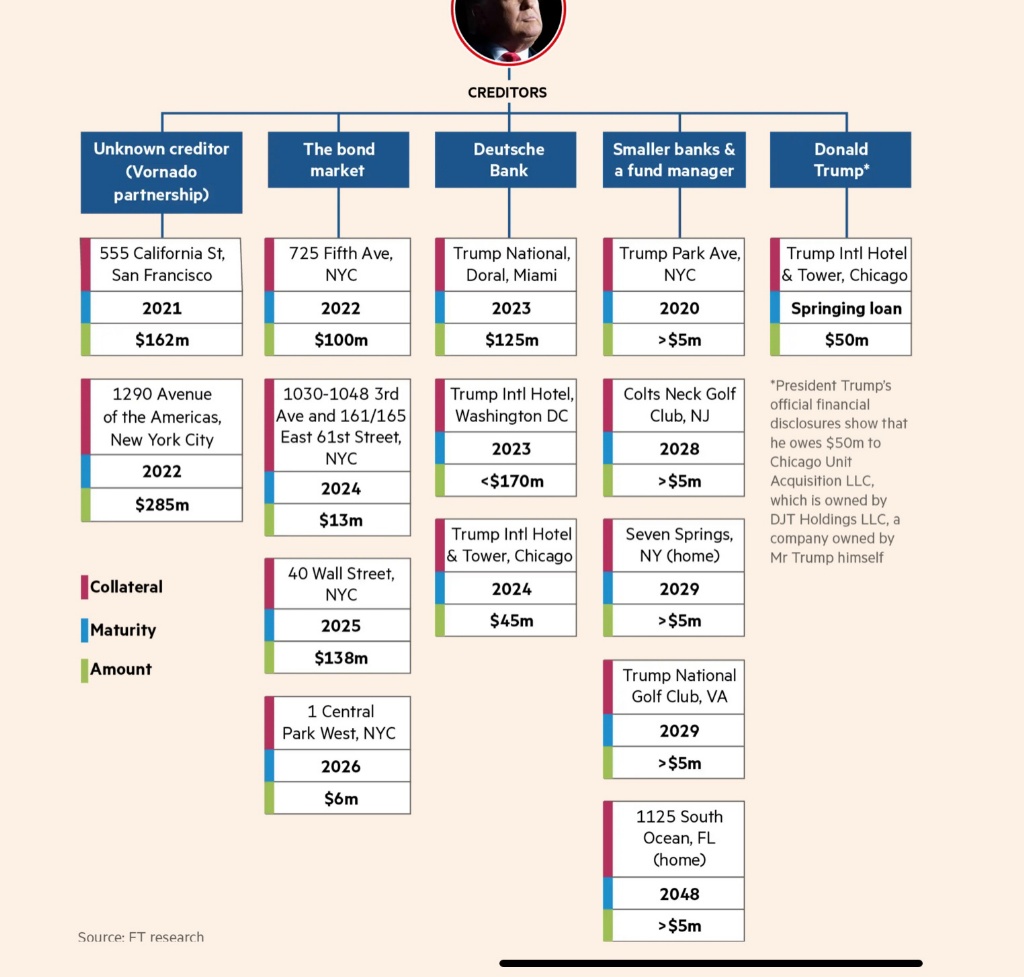

Trump’s debts

Source: Financial Times today.

Other, possibly interesting, links

-

470 West Vista Chino, Palm Springs, California. Yeah, but where do the humans live? Link

-

Canadian book makes shortlist for oddest book title of the year. A Dog Pissing at the Edge of a Path competes with 5 other contenders. You do wonder about people sometimes. Link

-

The longest-lived institutions in the world. From the Long Now Foundation, which tres to take the long view of everything. Link.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!