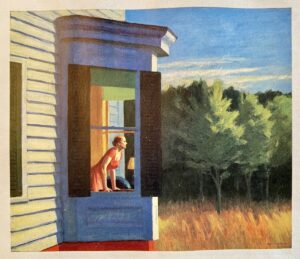

What holiday cottages should be like

From my favourite village in North Norfolk

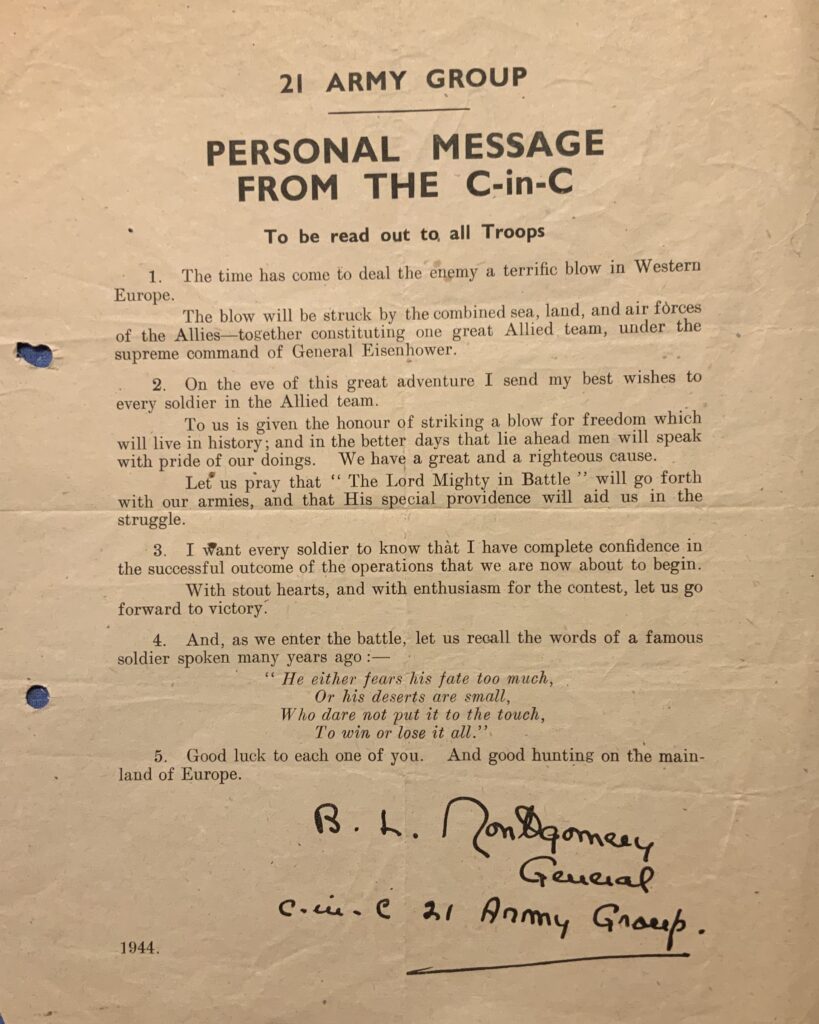

Quote of the Day

”Golf is a game that is played on a five-inch course — the distance between your ears”.

- Bobby (Robert Trent) Jones, the great American golfer.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

The Wailin’ Jennys | Bird Song Link

Microsoft Thinks You’ve Been Missing Your Commute in Lockdown

A forthcoming feature — ‘Virtual commutes’ — on Teams aims to rebuild the boundaries between work and home life, and signify Microsoft’s move into corporate well-being.

At first I thought this was a spoof. After all, if there’s one area where remote working scores it is in eliminating the daily commute. But,…

The daily commute may have caused its share of headaches, but it at least helped workers define a start and end to their workday while offering a set time to think away from the demands and distractions of the home and office. That positive side of the commute is what Microsoft hopes to re-create.

The Teams update next year will let users schedule virtual commutes at the beginning and end of each shift. Instead of reliving 8 a.m. or 6 p.m. packed subway rides or highway traffic jams in virtual reality, users will be prompted by the platform to set goals in the morning and reflect on the day in the evening.

The virtual commute feature represents Teams’ move into employee wellness, said Kamal Janardhan, general manager for workplace analytics and MyAnalytics at Microsoft 365, the parent division of Teams. The company historically has focused on employee connectivity and productivity.

“Enterprises across the world right now are coming to us and saying, ‘I don’t think we will have organizational resilience if we don’t make well-being a priority,’” Ms. Janardhan said. “I think we at Microsoft have a role, almost a responsibility, to give enterprises the capabilities to create these better daily structures and help people be their best.”

Interesting that idea that the daily commute enables people to “set goals in the morning and reflect on the day in the evening”. I’ve occasionally had to do a daily commute to London when working on a particular consultancy gig, and the thing I hated most about it was the evening return in a train packed with exhausted workers staring dully at their phones. Somehow, I don’t think they were reflecting on their days in a calm meditative mood. They were simply knackered.

Political Economy After Neoliberalism

Long read of the day from the Boston Review. It’s a thoughtful essay by Neil Fligstein and Steven Vogel on “Political Economy after Neoliberalism”. Fligstein is a Professor of Sociology at Berkeley, and the author of The Architecture of Markets. Vogel is a Professor of Political Science at Berkeley and the author of Marketcraft: How Governments Make Markets Work, so they’re heavy-duty thinkers.

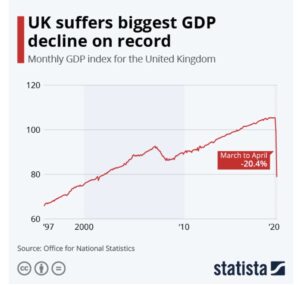

Starting from the fact that Western democracies have for forty or more years been governed by political elites who have drunk the Kool Aid of neoliberalist ideas about the primacy of markets and the inadequacy of the state, Fligstein and Vogel argue that if anything demonstrates the inadequacy of markets and the centrality of government it’s our experience since February. “The pandemic has exposed the fallacies of the neoliberal paradigm,” they write. “The market could not keep businesses running or people working.”

As if to highlight that fact, as economies have struggled desperately to contain the economic consequences of the plague, the stock market has been roaring ahead.

Flkigstein and Vogel propose three ‘core principles’ of an alternative political economy. They then illustrate these principles by discussing the dynamics of the American political economy, focusing particularly on the rise of “shareholder capitalism” in the 1980s. Finally, they apply the principles to the ongoing national policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, comparing the United States to Germany.

What are their ‘core principles’?

The first is that governments and markets are co-constituted. Government regulation is not an intrusion into the market but rather a prerequisite for a functioning market economy. Without government, the rule of law, the infrastructure of public order and so on, markets will run wild. Societies need markets; but markets also need society.

The second principle is that “real-world political economy hinges on power, both political and market power. Specific forms of market governance … do not arise naturally or innocently. They are the product of power struggles between firms, industries, workers, and governments within particular markets and in the political arena.”

The third principle is that there is more than one way to organize society to achieve economic growth, equity, and access to valued goods and services.

The balance of power between government, workers, and firms differs greatly across countries and time. And the different power balances in different countries shape distinctive national trajectories of policies. We can expect that the governing institutions will reinforce the status-quo balance of power, particularly in a crisis. It is rare for any one set of actors to have total control in a society, a condition that would lead to extreme rent-seeking behavior. Instead we see constant contestation between different sets of organized actors but a general balance of power that reflects the dominance of one side or another.

The essay goes on to argue that abandoning the neoliberal lens of government versus market and the “one best way” perspective opens up the possibility of a profound rethinking of economic policy that seeks to learn from the great variety of capitalisms that actually exist.

It’s a great essay — one of the only ones I’ve seen that tries to grapple realistically with the challenge of envisaging a more sustainable economic system as societies emerge from the pandemic.

Trump’s death wish

Watching Trump in recent weeks has been a weird experience. It’s like being a spectator at a live show in which the performer is losing his mind. And as I was thinking this I came on something that Judith Butler wrote in the London Review of Book a year ago:

When commentators speak of Trump’s ‘death wish’, they are on to something, though maybe not quite what they imagine. The death drive, in Freud, is manifested in actions characterised by compulsive repetition and destructiveness, and though it may be attached to pleasure and excitement, it is not governed by the logic of wish fulfilment. Repetitive action unguided by a wish for pleasure takes distinctive forms: the deterioration of the human organism in its effort to return to a time before individuated life; the nightmarish repetition of traumatic material without resolution; the externalisation of destructiveness through potentially murderous behaviour. Both suicide and murder are extreme consequences of a death drive left unchecked. The death drive works in fugitive ways, and is fundamentally opportunistic: it can be identified only through the phenomena on which it seizes and surfs. It may operate in the midst of moments of radical desire, pleasure, an intense sense of life. But it also operates in moments of triumphalism, the bold demonstration of power or strength, or in states of extreme conviction. Only later, if ever, comes the jolt of realisation that what was supposed to be empowering and exciting was in fact serving a more destructive purpose.

I do wonder what will happen to him when he loses the election and loses his frantic campaign then to discredit the results and is eventually — by whatever means the American Republic can muster to save its Constitution — physically ejected from office. Narcissists don’t take failure and humiliation well.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!