This morning’s Observer column:

When Edward Snowden first revealed the extent of government surveillance of our online lives, the then foreign secretary, William (now Lord) Hague, immediately trotted out the old chestnut: “If you have nothing to hide, then you have nothing to fear.” This prompted replies along the lines of: “Well then, foreign secretary, can we have that photograph of you shaving while naked?”, which made us laugh, perhaps, but rather diverted us from pondering the absurdity of Hague’s remark. Most people have nothing to hide, but that doesn’t give the state the right to see them as fair game for intrusive surveillance.

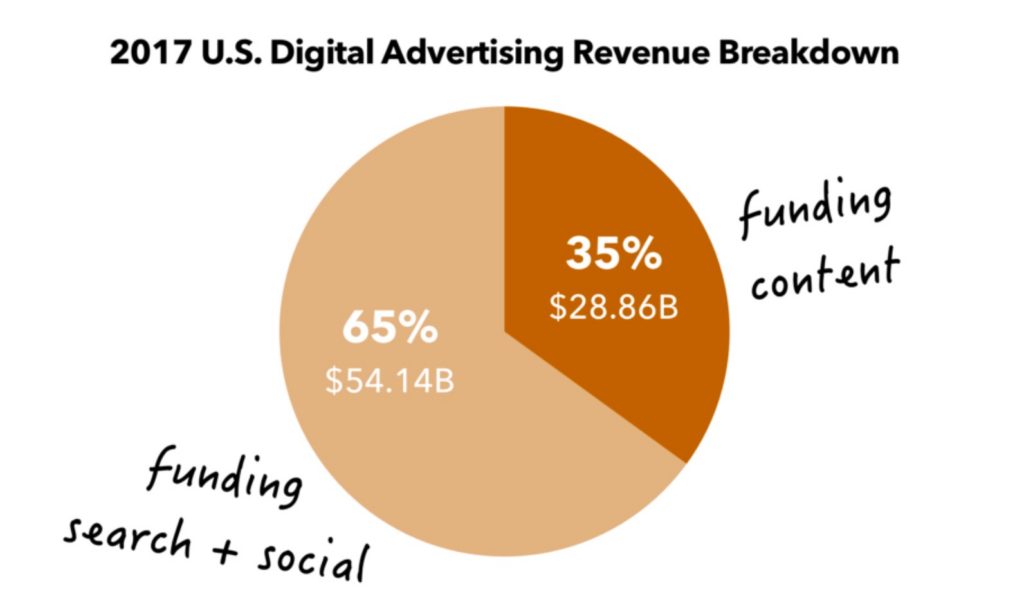

During the hoo-ha, one of the spooks with whom I discussed Snowden’s revelations waxed indignant about our coverage of the story. What bugged him (pardon the pun) was the unfairness of having state agencies pilloried, while firms such as Google and Facebook, which, in his opinion, conducted much more intensive surveillance than the NSA or GCHQ, got off scot free. His argument was that he and his colleagues were at least subject to some degree of democratic oversight, but the companies, whose business model is essentially “surveillance capitalism”, were entirely unregulated.

He was right…