Terrific cinematic critique of the Sorkin/Fincher film by Jim Emerson. Sample:

Since it came out last fall, I’d almost forgotten what an exhilarating information-overload experience David Fincher’s ‘The Social Network’is. Cut and composed and performed with breathless, jittery speed, it’s a movie that consists of virtually nothing but conversations in rooms (the attempted, missed, short-circuited, coded connections that struck me when I first saw it). It’s action-packed — enough to give you whiplash, watching all the elements interacting within the 2.40:1 widescreen frame — even though there are no ‘action sequences’ (car chases, shootouts, fist fights, acrobatic stunts, etc.); the filmmaking is charged with energy without falling back on today’s routinely frenetic, handheld run-and-gun/snatch-and-grab camerawork (the camera is generally mounted on a tripod; when it moves, it’s on a crane or a dolly — often for establishing shots or a shift in perspective that brings a new element into the frame). Smart, quick, efficient.

Because I’m not a film buff, I’d never come across this kind of criticism before. But I know this particular film well, and suddenly began to see it in a new light.

Here, for example, is Emerson’s analysis of the opening sequence:

The crunchy guitar riff starts over the Columbia Pictures logo and then the crowd noise comes up, the music drops down, and before the logo fades to black and the first image appears, we hear Mark (Jesse Eisenberg) speaking the movie’s opening line — a question that’s also a challenge: “Did you know there are more people with genius IQs living in China than there are people of any kind living in the United States?” What follows is a blisteringly fast-paced screwball comedy exchange (“His Girl Friday” through a 64-bit dual-core processor) between Mark and his girlfriend (not for very much longer ) Erica in which nearly every line is a misunderstanding (intentional or unintentional), a sarcastic jab, a leap of logic, a block, an interruption, a feint, an abrupt shift in the angle of attack, a diversion, a retreat, a refinement, a recapitulation (I’m sure there are many fencing terms that apply to the various conversational strategies employed here)…

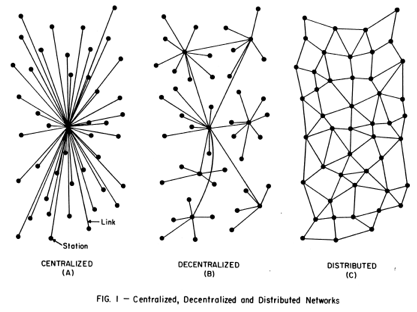

The scene offers just a few variations on some simple camera set-ups, deployed at high speed. Erica (Rooney Mara) is always on the left, Mark on the right (even in their individual close-ups they’re slightly shifted to those positions in the frame). The cutting is as quick and nervous and aggressive as the dialog, ricocheting from volley to return (and reaction shot to reaction shot). Most edits are right at the end of each character’s lines — there are hardly any pauses between them — so that the effect is like watching an intense two-camera tennis match, cutting from one side of the net to the other.

Only once after the opening shot does Fincher offer a balanced two-shot, as Erica presents an opportunity to disarm the conversation/confrontation and take it in a neutral direction: “Should we get something to eat?” Superficially, Mark makes a similar counter-offer, but it’s really another challenge: “Would you like to talk about something else?” And then we’re back to the over-the-shoulder shots (moving into close-ups) as Erica dives back in: “No, it’s just since the beginning of the conversation about finals club I think I may have missed a birthday.” By the time Mark tries to circle back to this juncture — “Do you want to get some food?” — it’s too late to recover that balance.

It would be fun to do a line-by-line, shot-by-shot accounting of the dynamics of this scene (or this whole movie), but let’s get to the point: The style here is a modern variation on some pretty straightforward, classical Hollywood filmmaking principles, distinguished two things: the velocity at which the scene is performed and cut; and the amount of information packed into the widescreen picture. (The idea of cutting a CinemaScope picture like this — especially for a simple, two-person dialog scene — would have been unthinkable until recently. Audiences for early anamorphic pictures in the 1950s and 1960s probably would have thrown up.)

Great stuff.