Here’s an interesting interview with Steven Levy, who has a new book about Google. Sigh: another one for the ‘must read’ pile.

Our apple tree

David Pogue on the axing of the Flip

David Pogue has an interesting take on Cisco’s decision to kill the Flip.

Gizmodo puts it, “Cisco just axed Flip, yeah, but the blame should be aimed squarely at the smartphone in your pocket.”

Which sounds logical—until you realize there is a far more satisfying explanation.

First, app phones like the iPhone represent only a few percent of cellphone sales. You know who buys app phones? Affluent, East Coast/West Coast, educated, New York Times-reading, Gizmodo-writing Americans.

But most of the world doesn’t buy iPhones. Of the 1 billion cellphones sold annually, a few million are iPhones. The masses still have regular cellphones that don’t capture video, let alone hi-def video. They’re the people who buy Flip camcorders. It’s wayyyyyy too soon for app phones to have killed off the camcorder.

Second, it isn’t true at all that nobody’s buying Flip camcorders. So far, 7 million people have bought them. Only a month ago, I was briefed by a Flip product manager on the newest model, which was to hit the market yesterday. He showed me a graph of the Flip’s sales; Flips now represent an astonishing 35 percent of the camcorder market. They’re the No. 1 bestselling camcorder on Amazon. They’re still selling fast.

Look at it this way: There are plenty of Flip copycats, from Kodak and other companies. They have only a fraction of the Flip’s popularity, but you don’t see them shutting down.

So why did Cisco kill off the flip?

I’ve spoken to a bunch of people in the industry, trying, in my human way, to figure out the logic here. It seems clear that Cisco, whose primary focus is making networking equipment for businesses, was all excited about getting into the consumer electronics game; that’s why it spent $590 million on Flip. But then, as John Chambers, Cisco’s chief executive, put it, the company decided to make “key, targeted moves as we align operations in support of our network-centric platform strategy.”

Which, in English, means, “We had no clue what we were doing.”

All right, fine. Cisco bit of more than it could chew. But why is it killing the Flip and not selling it?

The most plausible reason is that Cisco wants the technology in the Flip more than it wants the business. Cisco is, after all, in the videoconferencing business, and the Flip’s video quality—for its size and price—was amazing. Maybe, in fact, that was Cisco’s plan all along. Buy the beloved Flip for its technology, then shut it down and fire 550 people.

And here’s something we didn’t know:

But there’s a second part of the tragedy, too, something that nobody knows. That new Flip that the product manager showed me was astonishing. It was called FlipLive, and it added one powerful new feature to the standard Flip: live broadcasting to the Internet.

That is, when you’re in a Wi-Fi hot spot, the entire world can see what you’re filming. You can post a link to Twitter or Facebook, or send an e-mail link to friends. Anyone who clicks the link can see what you’re seeing, in real time—thousands of people at once.

Think how amazing that would be. The world could tune in, live, to join you in watching concerts. Shuttle launches. The plane in the Hudson. College lectures. Apple keynote speeches.

Or your relative could join you for smaller, more personal events: weddings. Birthday parties. Graduations. First steps.

And the FlipLive was supposed to ship yesterday. April 13. The day after Cisco killed the Flip.

The pollen collector

Have you ever wondered how bees collect pollen? I did–until the other day.

The Digital Public Library of America Project

From the The Harvard Crimson.

Harvard is solidifying plans to lead one of the largest national efforts to create a digitized public library.

The proposed Digital Public Library of America will serve as an open online collection of digitized books and texts that project leaders hope could one day incorporate every volume ever published.

Guided by a Steering Committee at the Harvard Law School’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society, the project remains in its initial planning phase. But in the wake of a New York District Court’s ruling last month against the Google Books Library Project, citing concerns of monopoly power, the spotlight has fallen on the DPLA, which will allow free access to the volumes.

There is a “need to pivot very quickly from the discussion phase to the implementation phase,” said Harvard Law Professor John G. Palfrey ’94, a co-director of the Berkman Center and a leader in the DPLA project.

The DPLA will be the product of a collaboration between the largest library systems in the nation, already including Harvard, the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and the Smithsonian Institution.

“The promise of the idea is attracting a lot of people at least to be involved even if they are skeptical of our ability to pull it off,” he said. “We have many of the biggest players at the table.”

If implemented successfully, the project will “make the cultural and scientific heritage of humanity available, free of charge, to all,” according to its online concept note.

Well, at least it gives the Crimson something to write about other than who’s suing Mark Zuckerberg at the moment.

From hero to zero in the blink of an eye: Cisco Shuts Down Flip

From today’s NYTimes.com.

It was one of the great tech start-up success stories of the last decade.

The Flip video camera, conceived by a few entrepreneurs in an office above Gump’s department store in San Francisco, went on sale in 2007, and quickly dominated the camcorder market.

The start-up sold two million of the pocket-size, easy-to-use cameras in the first two years. Then, in 2009, the founders cashed out and sold to Cisco Systems, the computer networking giant, for $590 million.

On Tuesday, Cisco announced it was shutting down its Flip video camera division.

Wow! I have a Flip. It’s a lovely gadget, and it came with quite elegant software. But I haven’t used it since I got an iPhone. Another illustration of the adage that the best camera is always the one you happen to have with you. It’s also a salutary lesson in how quickly this ecosystem can change.

Bet the guys who sold out to Cisco are laughing all the way to the bank.

James Gleick and the mystery of information

In today’s Observer there’s a conversation between me and James Gleick, whose book, The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood has just been published in the UK.

Here’s a paradox: we live in an “information age” and yet information is a maddeningly elusive concept. We habitually confuse it with data, on the one hand, and with knowledge on the other. And yet it’s neither. There’s an arcane mathematical discipline called “information theory” that underpins all digital communications nowadays and yet resolutely disdains to make any connection between information and meaning. It would take a brave author to pursue such an elusive quarry. Or a foolhardy one.

James Gleick is an accomplished stalker of mysterious ideas. His first book, Chaos (1987), provided a compelling introduction to a new science of disorder, unpredictability and complex systems. His new book, The Information, is in the same tradition. It’s a learned, discursive, sometimes wayward exploration of a very complicated subject…

I had a nice email this morning from Chris Stewart, a reader in Australia, who had just seen the piece. It reminded him, he said of a limerick that did the rounds in late 1960s Information Science circles. “I have”, he writes, “no idea who wrote it and after quoting it for more than 40 years no one has claimed it …”.

“Shannon and Weaver and I

Have found it instructive to try

To measure sagacity

And channel capacity

With sigma p i log p i”

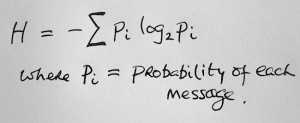

Which is a nice way of summarising Shannon’s formula for information as the measure of ‘unexpectedness’ of a message — H, as here:

“Weaver” refers to Warren Weaver who wrote a piece for Scientific American (“The Mathematics of Communication”, July 1949, p 11-15) explaining the significance of Shannon’s original paper, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” which had been published in two issues of the Bell Systems Technical Journal in 1948. The book, The Mathematical Theory of Communication by Shannon and Weaver, was published in 1949. It consisted of Shannon’s journal articles plus Weaver’s more accessible explanation.

Maddeningly, I can’t find a copy of Weaver’s SciAm article online, though I’m sure it’s around somewhere. And the SciAm search engine denies all knowledge of Warren Weaver.

Still, apropos the ditty forwarded by Chris Stewart, it’s good to know that Limerick, Ireland’s fourth city, is located on the Shannon, which is Ireland’s largest river.

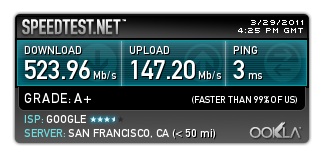

Amazon’s new Cloud Drive rains on everyone’s parade

This morning’s Observer column.

“Impetuosity and audacity,” wrote Machiavelli, “often achieve what ordinary means fail to achieve.” If you doubt that, may I propose a visit to the upper echelons of Apple, Google and Sony, where steam might be observed venting from every orifice of senior executives? If you do undertake such a visit, do not under any circumstances mention the word “Amazon”.

The proximate cause of all this corporate spleen is the launch last week of Amazon’s Cloud Drive service. At first sight, it seems straightforward: it looks like a digital locker in which one may for a fee securely store one’s digital assets in the internet ‘cloud’. “Anything digital, securely stored,” runs the blurb, “available anywhere.” The first 5GB of storage is free, with more available at an annual cost of a dollar per gigabyte. Upload files to your "cloud drive", where they are stored online and from where they can be accessed by any device that you own.

So far, so innocuous. It’s not the online storage business that has Apple, Google & Co spitting feathers, but the Amazon CloudPlayer which goes along with the digital locker…

The Master Switch

My review of Tim Wu’s new book.

At the heart of this fascinating book is one of the central questions of our age – rendered more urgent by recent events in the Arab world. The question is this: is the internet a revolutionary innovation, something that will overthrow the established order? Or will it turn out to have been just an unruly technology that the ancien regime will eventually capture and subdue?

Faced with the upheavals triggered by the network so far in economics, social life and politics, most people would probably say that the internet is indeed sui generis. But Professor Wu is not so sure, and therein lies the importance of his book. If the internet does indeed succeed in escaping the controlling embrace of corporations or governments, he argues, then it will be a historic first. For every other modern communications technology – telephone, radio, cinema and TV – has eventually succumbed to these forces…