“At some point soon it will almost be more embarrassing for a retailer if you haven’t been hacked than if you have”.

Krugman on Amazon’s abuse of market power

Paul Krugman had an interesting column about Amazon the other day. He dives straight in:

Amazon.com, the giant online retailer, has too much power, and it uses that power in ways that hurt America.

O.K., I know that was kind of abrupt. But I wanted to get the central point out there right away, because discussions of Amazon tend, all too often, to get lost in side issues.

Among those ‘side issues’ are the fact that Amazon is good for book buyers and good at customer service (which it is). Krugman is a Prime subscriber, as am I. “The desirability of new technology”, he writes,

“or even Amazon’s effective use of that technology, is not the issue. After all, John D. Rockefeller and his associates were pretty good at the oil business too — but Standard Oil nonetheless had too much power, and public action to curb that power was essential”.

Krugman sees Amazon’s tactics in its dispute with the publisher Hachette as an exact analogy to Standard Oil’s treatment of rail companies that refused to grant the company special discounts for shipping its oil. Amazon is delaying and impeding the sale of Hachette titles on its webssite, because Hachette won’t agree to give discounts to Amazon on the same scale as other publishers apparently do.

In economic jargon, Amazon is not acting like a monopolist (i.e. gouging customers) — not yet anyway. Instead it’s behaving like a monopsonist — i.e. a dominant buyer with the power to push down suppliers’ prices.

Way back in the 1920s, it was that kind of behaviour that triggered state action. “The robber baron era ended”, Krugman writes, “when we as a nation decided that some business tactics were out of line.” The question is whether analogous state action is now likely.

You only have to ask the question to know the answer. The neoliberal ideology has so entered our rulers’ souls that the concept of taking on Amazon is not only verboten, but unthinkable.

Two degrees

Q: What’s the difference between a rise in global temperature of 2 degrees C and 4 degrees?

A: Human civilisation.

Who says? John Schellnhuber, one of the world’s most influential climate scientists, quoted in Paul Kingsnorth’s LRB Review of George Marshall’s new book, Don’t Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change.

According to Kingsnorth’s summary of Marshall’s thinking, four degrees of warming is likely

“to bring heatwaves of magnitudes never experienced before, and temperatures not seen on Earth in the last five million years. Forty per cent of plant and animal species would be at risk of extinction, a third of Asian rainforests would be under threat and most of the Amazon would be at high risk of burning down. Crop yields would collapse, possibly by a third in Africa. US production of corn, soy beans and cotton would fall by up to 82 per cent. Four degrees guarantees the total melting of the Greenland ice sheet and probably the Western Antarctic ice sheet, which would raise sea levels by more than thirty feet. Two thirds of the world’s major cities would wind up underwater. And we aren’t looking at a multigenerational time-scale: we may see a four degree rise over the next sixty years.”

After Snowden, what?

This morning’s Observer column.

Many moons ago, shortly after Edward Snowden’s revelations about the NSA first appeared, I wrote a column which began, “Repeat after me: Edward Snowden is not the story”. I was infuriated by the way the mainstream media was focusing not on the import of what he had revealed, but on the trivia: Snowden’s personality, facial hair (or absence thereof), whereabouts, family background, girlfriend, etc. The usual crap, in other words. It was like having a chap tell us that the government was poisoning the water supply and concentrating instead on whom he had friended on Facebook.

Mercifully, we have moved on a bit since then. The important thing now, it seems to me, is to consider a new question: given what we now know, what should we do about it? What could we realistically do? Will we, in fact, do anything? And if the latter, where are we heading as democracies?

I tried to put some of these questions to Snowden at the Observer Ideas festival last Sunday via a Skype link that proved comically dysfunctional. The comedy in using a technology to which the NSA has a backdoor was not lost on the (large) audience — or on Snowden, who coped gracefully with it. But it was a bit like trying to have a philosophical discussion using smoke signals. So let’s have another go.

First, what could we do to curb comprehensive surveillance of the net?

Value for money in the surveillance business

Has anyone in government done a cost-benefit analysis on bulk surveillance? I mean to say, we’re spending fortunes on this stuff (in the US something like $100B a year ). Does anyone have any idea of whether it’s really worth it? Could we be spending all that dosh more wisely and getting better anti-terrorist results?

Which is why I found this exchange between a questioner and William Binney, the former Technical Director of the NSA fascinating.

Question: Other than making money off of like these NSA contracts, what capabilities do these companies [i.e. defence contractors like Booz Allen Hamilton — Snowden’s employers] *have, what other value are they generating for themselves?

William Binney: Nobody does return on investment at NSA. They don’t.

I mean, if they did return on investment, they would throw away everything except TRAFFICTHIEF and maybe some graphing programs out of MAINWAY– they’d throw all of this away. They wouldn’t have built Bluffdale [Utah], that $2.3B or whatever it is– facility to store data. This is all the data from PINWALE and MARINA and all that stuff is going out there, being stored. So they wouldn’t have to buy that at all. They’d be more effective, because they wouldn’t be buried. So at any rate, that’s what they’re doing.

The exchange comes from an absolutely riveting report of a presentation that Binney gave in which he explained some of the Snowden material.

The New Yorker’s interview with Edward Snowden

Unmissable.

Carole Cadwalladr’s report of my conversation with him last Sunday is here.

Old cryptopanic in new iBottles

Repeat after me:

A ‘backdoor’ for law enforcement is a deliberately introduced security vulnerability, a form of architected breach.

Or, if you’d like the more sophisticated version

It requires a system to be designed to permit access to a user’s data against the user’s wishes, and such a system is necessarily less secure than one designed without such a feature. As computer scientist Matthew Green explains in a recent Slate column (and, with several eminent colleagues, in a longer 2013 paper) it is damn near impossible to create a security vulnerability that can only be exploited by “the good guys.” Activist Eva Galperin puts the point pithily: “Once you build a back door, you rarely get to decide who walks through it.” Even if your noble intention is only to make criminals more vulnerable to police, the unavoidable cost of doing so in practice is making the overwhelming majority of law-abiding users more vulnerable to criminals.

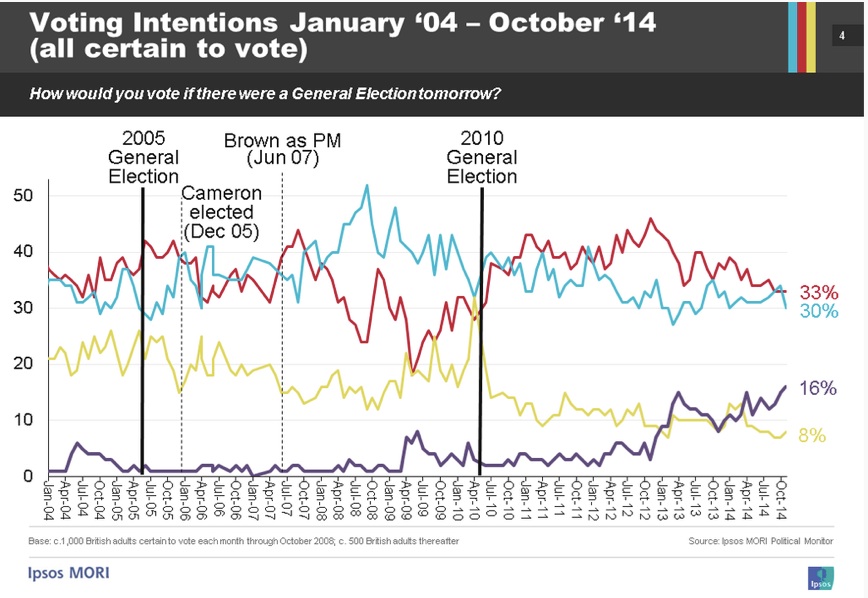

Why a month is a long time in (UK) politics

Bruce Schneier’s next book

Title: Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles to Collect Your Data and Control Your World

Publisher: WW Norton

Publication date: March 9, 2015

Table of Contents

Part 1: The World We’re Creating

Chapter 1: Data as a By-Product of Computing

Chapter 2: Data as Surveillance

Chapter 3: Analyzing our Data

Chapter 4: The Business of Surveillance

Chapter 5: Government Surveillance and Control

Chapter 6: Consolidation of Institutional Surveillance

Part 2: What’s at Stake

Chapter 7: Political Liberty and Justice

Chapter 8: Commercial Fairness and Equality

Chapter 9: Business Competitiveness

Chapter 10: Privacy

Chapter 11: Security

Part 3: What to Do About It

Chapter 12: Principles

Chapter 13: Solutions for Government

Chapter 14: Solutions for Corporations

Chapter 15: Solutions for the Rest of Us

Chapter 16: Social Norms and the Big Data Trade-Off

Something to be pre-ordered, methinks.

How some of us feel about our inboxes

A typically beautiful piece of letter-carving by the Cardozo-Kindersley Workshop.