- Is Apple’s marketing division over-ruling engineering? Or: why are there so many problems with iOS 13 and Catalina?

- The Medieval Myth of Notre Dame

- Some things are improving: the German Synagogue Shooter’s Twitch Video Didn’t Go Viral.

- Ken Thompson’s ancient password has finally been cracked. (It was a chess move.)

- Jeffrey Epstein’s Old Science Blog. It’s as Weird as You Think.

Quote of the Day

“Politics, as a practice, has always been the systematic organization of hatreds.”

Henry Adams

Autumn

Sauce for the goose…

You have to hand it to Elizabeth Warren sometimes. Annoyed (as I am) about Facebook’s insistence on continuing to allow untruthful political ads to run on the platform, Warren placed an untruthful ad herself to see what happened (and, clearly, to annoy Mark Zuckerberg. Here’s the gist of the NYT report of the jape:

The Democratic presidential candidate bought a political ad on the social network this past week that purposefully includes false claims about Facebook’s chief executive, Mark Zuckerberg, and President Trump to goad the social network to remove misinformation in political ads ahead of the 2020 presidential election.

The ad, placed widely on Facebook beginning on Thursday, starts with Ms. Warren announcing “Breaking news.” The ad then goes on to say that Facebook and Mr. Zuckerberg are backing the re-election of Trump. Neither Mr. Zuckerberg nor the Silicon Valley company has announced their support of a candidate.

“You’re probably shocked, and you might be thinking, ‘how could this possibly be true?’ Well, it’s not,” Ms. Warren said in the ad.

In a series of tweets on Saturday, Ms. Warren, a senator from Massachusetts, said she had deliberately made an ad with lies because Facebook had previously allowed politicians to place ads with false claims. “We decided to see just how far it goes,” Ms. Warren wrote, calling Facebook a “disinformation-for-profit machine” and adding that Mr. Zuckerberg should be held accountable.

Lovely.

Time to stop kowtowing to China

My OpEd piece in today’s Observer:

What’s happening is that the delusions of decades of wishful western thinking about China are finally being exposed by the crisis in Hong Kong. These delusions took various forms over the years. First, there was the theory that since economic development required capitalism, then that would bring democracy. The Chinese said they would have one without the other, thank you very much. And they did.

Then there was the fantasy that adopting the internet would bring openness and therefore democracy. Same story. The most recent delusion is that China’s current turn towards totalitarianism is doomed because such societies stagnate and decay. Xi Jinping and his colleagues beg to differ: they believe that information technology can enable them to have total control without sclerosis. Given their track record, it’d be unwise to bet against them…

Why the blogosphere matters

This morning’s Observer column:

Last Monday was a significant anniversary in the evolution of the web. It was 25 years to the day since the first serious blog appeared. It was called Scripting News and the url was (and remains) at scripting.com. Its author is a software wizard named Dave Winer, who’s updated it every day since 1994. And despite its wide readership, it has never run ads. This may be partly because Dave doesn’t need the money (he sold his company to Symantec in 1987 for a substantial sum) but it’s mainly because he didn’t want to compete for the attention of his readers. “I see running ads on my blog,” he once wrote, “as picking up loose change that’s fallen out of peoples’ pockets. I want to hit a home run. I’m swinging for the fences. Not picking up litter.”

When some innovators cash out big, as Winer did, they more or less retire – play golf, buy a yacht and generally hang out in luxury. Not so Dave. He has a long string of innovations to his name, including outliner and blogging software, RSS syndication, the outline processor markup language OPML and podcasting, of which he was a pioneer.

And his daily blog at scripting.com continues to be a must-read for anyone interested in the intersection between technology and politics. Winer has a quirky, perceptive, liberal and sometimes contrarian take on just about anything that appears on his radar. He is the nearest thing the web has to an international treasure.

He’s also a reminder of the importance of blogging, a phenomenon that has been overshadowed as social media exploded and sucked much of the oxygen out of our information environment…

Never forget the punchline

At a seminar about “The Cost of Culture“ this afternoon Nicholas Hytner, the theatre director (and former Director of the National Theatre), quoted John O’Gaunt’s famous speech in Shakespeare’s Richard II — the one beloved of Brexit enthusiasts:

This royal throne of kings, this scepter’d isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall,

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands,

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England.

Then Hytner paused, before reminding the audience of how the speech ends:

That England, that was wont to conquer others,

Hath made a shameful conquest of itself.

Given that he was talking to an audience comprised (I’d guess) largely of Remainers— and that Brexit seems to be largely an expression of English nationalism — this went down rather well.

Another Dyson triumph!

Well, well. ‘Sir’ James Dyson, the billionaire British inventor and enthusiastic advocate of Brexit (who prudently decamped to Singapore before that dream came to pass), has now revealed that his grand plan to produce a world-beating electric car has been abandoned. Apparently it was a terrific vehicle (no evidence available to date for that claim) but there was no way the company could make it commercially viable.

Still, its inventor can stay comfortably in Singapore — at least until his fellow-ideologues have succeeded in turning the UK into Singapore 2.0.

Why redistribution matters

From an interesting blog post by Noah Smith:

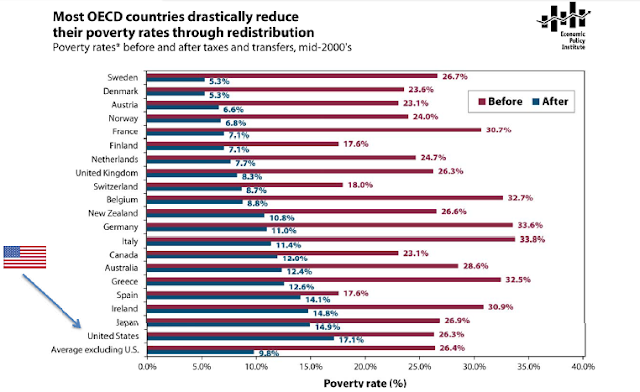

But since the time of Vilfredo Pareto it has been well-known that every country has a substantial amount of market poverty – that is, poverty before taxes and transfers. Here is a graph from the Economic Policy Institute of market poverty rates vs. post-transfer poverty rates:

In other words, no matter how you set up your system, you’re going to get a lot of people who will experience relative poverty without government transfers. Hence, the social safety net matters a lot.

Capitalism is not a bad thing. Capitalism, in some form, is an amazing engine of wealth creation. Capitalism of some sort, as far as we know, is absolutely necessary to maintaining high standards of living and eliminating absolute poverty.

But capitalism is not omnipotent. Drowning government in a bathtub and leaving individuals to sink or swim on their own in a free market economy will result in some people failing and being poor, no matter how well they behave. Thus, any capitalist system can be improved with a social safety net.

Yep.This is news to many ideologues in the UK and the US. But it’s central to Nicholas Colin’s argument in his book Hedge.

Know-towing to China, contd.

It goes on and on. For example, this report from the NYT:

SAN FRANCISCO — Apple removed an app late Wednesday that enabled protesters in Hong Kong to track the police, a day after facing intense criticism from Chinese state media for it, plunging the technology giant deeper into the complicated politics of a country that is fundamental to its business.

Apple said it was withdrawing the app, called HKmap.live, from its App Store just days after approving it because authorities in Hong Kong said protesters were using it to attack the police in the semiautonomous city.

A day earlier, People’s Daily, the flagship newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party, published an editorial that accused Apple of aiding “rioters” in Hong Kong. “Letting poisonous software have its way is a betrayal of the Chinese people’s feelings,” said the article, which was written under a pseudonym that translates into “Calming the Waves.”

In a statement on Wednesday, Apple said, “The app displays police locations and we have verified with the Hong Kong Cybersecurity and Technology Crime Bureau that the app has been used to target and ambush police, threaten public safety, and criminals have used it to victimize residents in areas where they know there is no law enforcement. This app violates our guidelines and local laws.”

And then this (about Apple again) from The Verge:

News organization Quartz tells The Verge that Apple has removed its mobile app from the Chinese version of its App Store after complaints from the Chinese government. According to Quartz, this is due to the publication’s ongoing coverage of the Hong Kong protests, and the company says its entire website has also been blocked from being accessed in mainland China.

The publication says it received a notice from Apple that the app “includes content that is illegal in China.”

In a statement, Quartz CEO Zach Seward, who assumed the role of chief executive just two days ago, tells The Verge that “We abhor this kind of government censorship of the internet, and have great coverage of how to get around such bans around the world.” The statement points to the publications’ coverage of VPNs, which can be used to bypass restrictions on accessing certain parts of the internet from mainland China. Quartz also links out to its coverage of the Hong Kong protests.

Apple capitulating to the Chinese government is nothing new. The company’s deep business interests in China, which include a majority of its consumer electronics supply chain, mean that in almost all cases, it abides by the country’s censorship policies and its sensitive reactions to any and all criticism of the Chinese government.

What’s so interesting about recent developments is that the magical thinking that most Western companies (and most governments, come to that) have indulged in about China has been exposed as fatuous wishful thinking. As de Gaulle famously observed decades ago, “Great nations do not have friends, only interests.” China is flexing its muscles.