David Cameron and Xi Jinping go to the pub

It’s called appeasement — famously defined by (I think) Winston Churchill as “being nice to the crocodile in the hope that he will eat you last”.

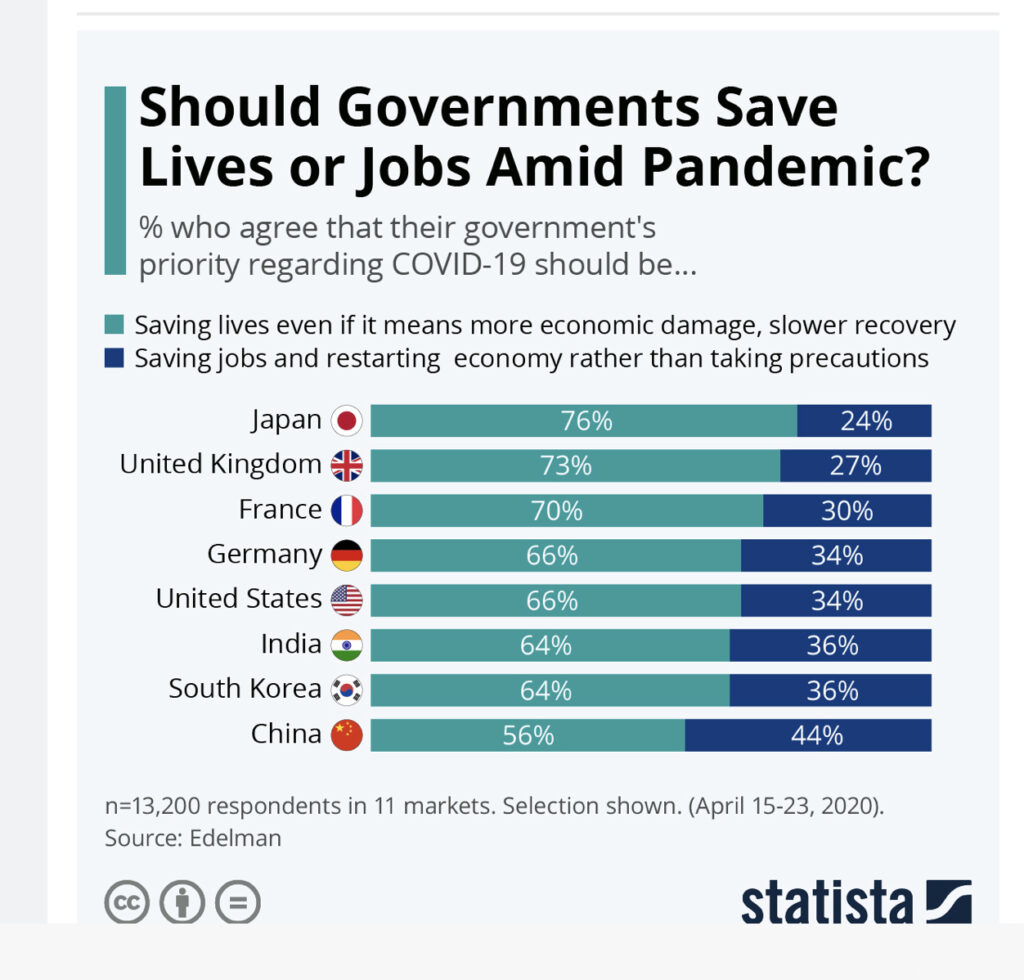

Citizens’ views about easing lockdowns

Suggests to me that expecting customers to flock back to stores etc. might be unduly optimistic. People are more cautious than their governments. And the UK’s subjects (they’re not citizens) are second in the list. Boris Johnson may be in for a surprise.

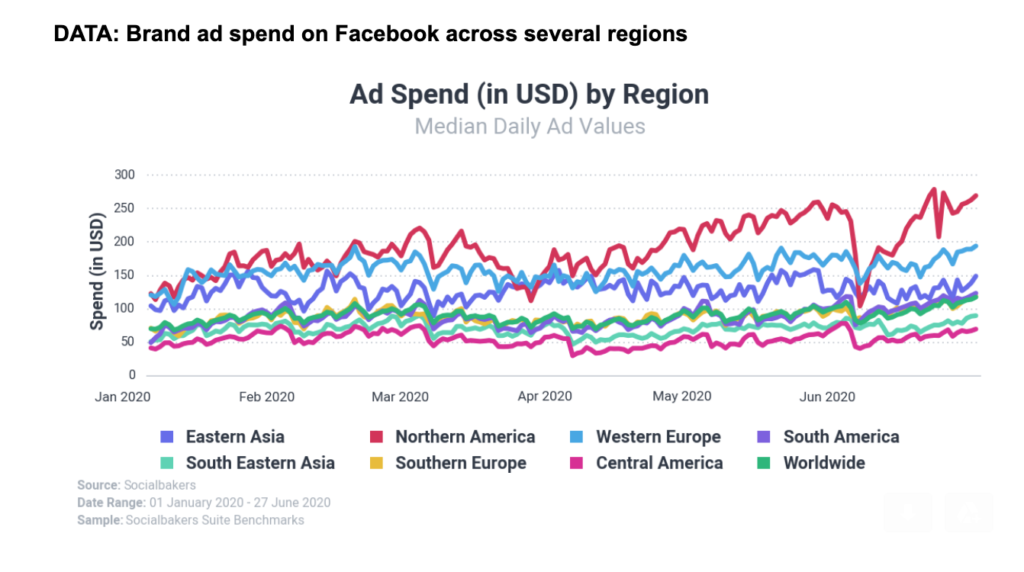

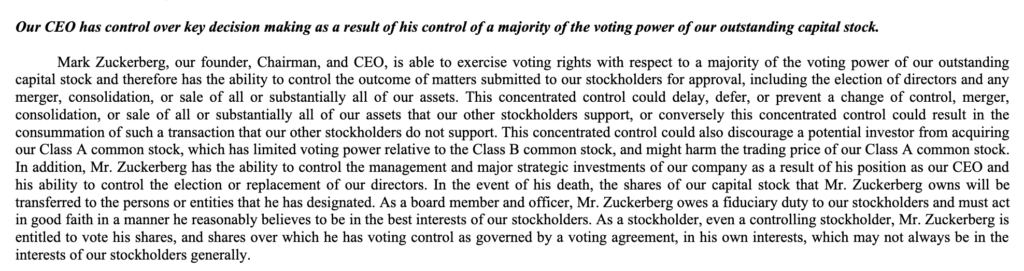

More naive illusions about Facebook

I don’t think the boycott will have anything other a marginal impact on the company.

Bossware: a real downside of working from home

Good investigation and an explainer from EFF — the Electronic Freedom Foundation.

Bossware typically lives on a computer or smartphone and has privileges to access data about everything that happens on that device. Most bossware collects, more or less, everything that the user does. The EFF looked at marketing materials, demos, and customer reviews to get a sense of how these tools work and produced a summary of the ways these products can surveil into general categories.

COVID-19 has pushed millions of people to work from home, and a flock of companies offering software for tracking workers has swooped in to pitch their products to employers across the country.

The services often sound relatively innocuous. Some vendors bill their tools as “automatic time tracking” or “workplace analytics” software. Others market to companies concerned about data breaches or intellectual property theft. We’ll call these tools, collectively, “bossware.” While aimed at helping employers, bossware puts workers’ privacy and security at risk by logging every click and keystroke, covertly gathering information for lawsuits, and using other spying features that go far beyond what is necessary and proportionate to manage a workforce.

This is not OK. When a home becomes an office, it remains a home. Workers should not be subject to nonconsensual surveillance or feel pressured to be scrutinized in their own homes to keep their jobs.

Great piece of work.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

What’s with the reluctance to wear masks?

Given that universal mask-wearing when in proximity to other people is the only way of having a reasonably normal life when the lockdowns ease, I’m baffled by (a) why there seems to be so much reluctance to wear masks (at least in Western countries), and (b) why they are not legally mandated in the UK. Sure, they don’t provide cast-iron guarantees of non-infection but they definitely reduce the risk.

One think that’s noticeable from the US is that some males in that benighted country (led by their Child-President) think there’s something girly about wearing masks. I don’t mind them dying as a result of this neurotic macho delusion. But I do mind the fact that, by not wearing masks, they continue to endanger others.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Back to the future on energy storage

One of the main objections to electricity generation by renewable sources is the hoary old question: what happens when the wind stops or there’s not enough light for solar panels to do the trick? After all, if an electricity grid can’t cope with demand, it has to shut down some parts of the grid until supply equals demand.

For years and years we’ve been listening to tech evangelists (no doubt led by Elon Musk) telling us that the only solution is massive battery-complexes. This is the usual tech-solutionist guff, and it conveniently overlooks the environmental and other costs of lithium-ion batteries, not to mention the fact that they’re no good for long-term storage.

So it was fascinating to hear Steven Chu, the Nobel laureate who was Obama’s Energy Secretary, explaining that there is a solution to the energy storage problem that’s been around for many decades. And no rocket science is required: just a familiarity with gravity. Here’s part of the Forbes report:

The most efficient energy storage technology may be as close as the nearest hill, according to former Energy Secretary Steven Chu, and almost as old.

“It turns out the most efficient energy storage is you take that electricity and you pump water up a hill,” Chu said Tuesday at the Stanford University Global Energy Forum.

When electricity is needed, you let the water flow down, spinning generators along the way. Pumped hydro can meet demand for seasonal storage instead of the four hours typical of lithium-ion batteries.

“There’s been a resurgence and a new look at pumped storage because it is the one thing we do have, and we know it works and lasts a long time,” Chu said, highlighting it first in a review of energy-storage technologies.

The way it works is that when demand on the grid is low, you use the surplus electricity to pump water uphill to a reservoir. Then if there’s a sudden surge in demand, you open the sluices and water rushes down and starts to spin generators. It’s just a variation on the hydro-power systems that some countries like Norway have relied upon for many decades.

What’s really quaint about this, for those with long memories, is that the UK was providing fast-response electric power since 1984 via the Donorwig pumped storage station in Wales. It was constructed in the abandoned Dinorwic slate quarry and to preserve the natural beauty of Snowdonia National Park, the power station itself is located deep inside the mountain Elidir Fawr, inside tunnels and caverns. The project – begun in 1974 and taking ten years to complete at a cost of £425 million – was the largest civil engineering contract ever awarded by the UK government at the time. And it paid for itself in two years.

En passant: in the Trump era doesn’t it seem weird that there was a time when the person in charge of the US Department of Energy who was not only a Nobel prize-winner, but understood that his job was to act in the public interest rather than as a shill for the coal industry.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

What it’s like trying to report on Facebook

Terrific piece in Columbia Journalism Review.. Here’s the gist, but it’s worth trading in full, especially if you work in media or tech journalism.

What Facebook has become is the press’s assignment editor, its distribution network, its great antagonist, devourer of its ad revenue, and, through corporate secrecy, a massive block to journalism’s core mission of democratic accountability. Whether journalists can survive these conditions to produce meaningful, critical work about Facebook depends as much on their own adaptability as it does on the backing of revenue-minded media owners who might not wish to antagonize one holder of the advertising duopoly during an unfolding economic calamity. Except for one or two premium-tier media properties, journalism needs Facebook more than Facebook needs journalism.

“I don’t think the adversarial relationship between Facebook and the press is going to change,” Biddle says. “It’s a question of whether Facebook is going to stop resenting it so obviously and realize that this is what comes with being an enormously powerful, enormously wealthy corporation.”

That’s why one of the themes of our our new research Centre in Cambridge is building journalistic capacity to interrogate the tech industry.

The blogchain: New potatoes

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!