Quote of the Day

“They would like to have the people come off. I’d rather have the people stay [on the ship]. … I would rather because I like the numbers being where they are. I don’t need to have the numbers double because of one ship that was not our fault.”

- Donald J. Trump, Acting President of the United States, March 4, while on a visit to the Centers for Disease Control, answering a question about whether passengers on the Grand Princess cruise ship should be allowed to disembark.

5G ‘protection’ in Glastonbury

Glastonbury is possibly the wackiest town in the UK. Maybe it’s something in the water supply. There’s a lovely post on the Quackometer blog about it.

The council published a report that called for an ending of 5G rollout. Several members of the working group that looked into the safety of 5G complained that the group had been taken over “by anti-5G activists and “spiritual healers”.

This is not surprising to anyone who has ever visited the town of Glastonbury. There is not a shop, pub, business or chip shop that has not been taken over by “spiritual healers” of one sort or another. You cannot walk down the High Street without being smothered in a fog of incense and patchouli. It is far easier to buy a dozen black candles and a pewter dragon than it is a pint of milk.

Science has no sanctuary in Glastonbury. Homeopaths, healers, hedge-witches and hippies all descend on the town to be at one with the Goddess.

There may be no science there, but there’s a lot of ‘technology’ — as the BBC Technology correspondent Rory Cellan-Jones discovered on a visit — after which he tweeted this:

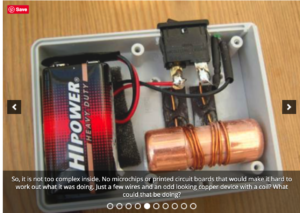

Further down, there’s a delicious analysis of an electronic device to ‘neutralise radiation’. Taking it apart reveals its innards:

This sophisticated device consists of a switch, a 9-volt battery, a length of standard copper pipe with two endpieces, and an LED bulb.

Not clear how much it sells for, but my guess is £50.

I’m in the wrong business.

Farewell to Beyond the Beyond

This is the title of what is, IMHO, the best essay on blogging ever written. If that seems an extravagant claim, stay tuned. But first, some context.

Bruce Sterling is one of the founders of the cyberpunk movement in science fiction, along with William Gibson, Rudy Rucker, John Shirley, Lewis Shiner, and Pat Cadigan. In addition, he is one of the subgenre’s chief ideological promulgators. But for me he’s always been the consummate blogger. His Beyond the Beyond blog has been running on Wired since 2003, but now — after 17 glorious years — he’s just written a final post.

So, the blog is formally ending this month, May MMXX.

My weblog is a collateral victim of Covid19, which has become a great worldwide excuse to stop whatever you were doing.

You see, this is a WIRED blog — in fact, it is the first ever WIRED blog — and WIRED and other Conde’ Nast publications are facing a planetary crisis. Basically, they’ve got no revenue stream, since the business model for glossy mags is advertisements for events and consumer goods.

If there are no big events due to pandemic, and nobody’s shopping much, either, then it’s mighty hard to keep a magazine empire afloat in midair. Instead, you’ve gotta fire staffers, shut down software, hunt new business models, re-organize and remove loose ends. There is probably no looser-end in the entire WIRED domain than this weblog.

So, in this extensive and self-indulgent conclusion, I’d like to summarize what I think I’ve learned by messing with this weblog for seventeen years.

I’ve been a passionate blogger since the late-1990s. It seemed to me that blogs were the first sign that the Internet was a technology that could finally enable the realisation of Jurgen Habermas’s concept of the ‘public sphere’. It met the three criteria for such a sphere:

- universal access — anybody could have access to the space;

- rational discussion on any subject; and

- disregard of rank or social status.

Initially, my blog was private. It was basically a simple website that I had created, with a very primitive layout. I regarded it as a kind of lab notebook — a place for jotting down ideas where I wouldn’t lose them. As it grew, I discovered that it became even more useful if I put a search engine on it. And then when Dave Winer came up with a blogging platform — Frontier — I switched to that and Memex 1.1 went public. It was named after Vannevar Bush’s concept of the ‘Memex’– a system for associative linking — which he first articulated in a paper in 1939 and eventually published in 1945, and which eventually led, via an indirect route, to Tim Berners-Lee’s concept of the World Wide Web. If you’re interested, the full story is told in my history of the Net.

And since then Memex 1.1 has been up and running.

I suppose one of the reasons why I like Bruce’s swansong is that his views on blogging resonate with mine — except that he articulates them much more clearly that I ever have. Over the years I’ve encountered puzzlement, suspicion, scepticism and occasionally ridicule for the dogged way I’ve persisted in an activity that many of my friends and colleagues consistently regarded as weird. My journalistic colleagues, in particular, were always bemused by Memex: but that was possibly because (at least until recently) journalists regarded anybody who wrote for no pay as clinically insane. In that, they were at one with Dr Johnson, who famously observed that “No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money”.

Still, there we are.

Bruce’s post is worth reading in its entirety, but here are a few gems:

…on its origins…

When I first started the “Beyond the Beyond” blog, I was a monthly WIRED columnist and a contributing editor. Wired magazine wanted to explore the newfangled medium of weblogs, and asked me to give that a try. I was doing plenty of Internet research to support my monthly Wired column, so I was nothing loath. I figured I would simply stick my research notes online. How hard could that be?

That wouldn’t cost me much more effort than the duty of writing my column — or so I imagined. Maybe readers would derive some benefit from seeing some odd, tangential stuff that couldn’t fit within a magazine’s paper limits. The stuff that was — you know — less mainstream acceptable, more sci-fi-ish, more far-out and beyond-ish — more Sterlingian.

… on its general remit …

Unlike most WIRED blogs, my blog never had any “beat” — it didn’t cover any subject matter in particular. It wasn’t even “journalism,” but more of a novelist’s “commonplace book,” sometimes almost a designer mood board.

… on its lack of a business model…

It was extremely Sterlingesque in sensibility, but it wasn’t a “Bruce Sterling” celebrity blog, because there was scarcely any Bruce Sterling material in it. I didn’t sell my books on the blog, cultivate the fan-base, plug my literary cronies; no, none of that standard authorly stuff

… on why he blogged…

I keep a lot of paper notebooks in my writerly practice. I’m not a diarist, but I’ve been known to write long screeds for an audience of one, meaning myself. That unpaid, unseen writing work has been some critically important writing for me — although I commonly destroy it. You don’t have creative power over words unless you can delete them.

It’s the writerly act of organizing and assembling inchoate thought that seems to helps me. That’s what I did with this blog; if I blogged something for “Beyond the Beyond,” then I had tightened it, I had brightened it. I had summarized it in some medium outside my own head. Posting on the blog was a form of psychic relief, a stream of consciousness that had moved from my eyes to my fingertips; by blogging, I removed things from the fog of vague interest and I oriented them toward possible creative use.

… on not having an ideal reader…

Also, the ideal “Beyond the Beyond” reader was never any fan of mine, or even a steady reader of the blog itself. I envisioned him or her as some nameless, unlikely character who darted in orthogonally, saw a link to some odd phenomenon unheard-of to him or her, and then careened off at a new angle, having made that novelty part of his life. They didn’t have to read the byline, or admire the writer’s literary skill, or pony up any money for enlightenment or entertainment. Maybe they would discover some small yet glimmering birthday-candle to set their life alight.

Blogging is akin to stand-up comedy — it’s not coherent drama, it’s a stream of wisecracks. It’s also like street art — just sort of there, stuck in the by-way, begging attention, then crumbling rapidly.

Lovely stuff. Worth celebrating.

Moral Crumple Zones

Pathbreaking academic paper by Madeleine Clare Elish which addresses the problem of how to assign culpability and responsibility when AI systems cause harm. Example: when a ‘self-driving’ car hits and hills a pedestrian, is the ‘safety driver’ (the human supervisor sitting in the car but not at the controls at the time of the accident) the agent who gets prosecuted for manslaughter? (This is a real case, btw.).

Although published ages ago (2016) this is still a pathbreaking paper. In it Elish comes up with a striking new concept.

I articulate the concept of a moral crumple zone to describe how responsibility for an action may be misattributed to a human actor who had limited control over the behavior of an automated or autonomous system.1Just as the crumple zone in a car is designed to absorb the force of impact in a crash, the human in a highly complex and automated system may become simply a component—accidentally or intentionally—that bears the brunt of the moral and legal responsibilities when the overall system malfunctions.

While the crumple zone in a car is meant to protect the human driver, the moral crumple zone protects the integrity of the technological system, at the expense of the nearest human operator. What is unique about the concept of a moral crumple zone is that it highlights how structural features of a system and the media’s portrayal of accidents may inadvertently take advantage of human operators (and their tendency to become “liability sponges”) to fill the gaps in accountability that may arise in the context of new and complex systems.

It’s interesting how the invention of a pithy phrase can help to focus attention, attention and understanding.

Writing the other day in Wired, Tom Simonite picked up on Elish’s insight:

People may find it even harder to clearly see the functions and failings of more sophisticated AI systems that continually adapt to their surroundings and experiences. “What does it mean to understand what a system does if it is dynamic and learning and we can’t count on our previous knowledge?” Elish asks. As we interact with more AI systems, perhaps our own remarkable capacity for learning will help us develop a theory of machine mind, to intuit their motivations and behavior. Or perhaps the solution lies in the machines, not us. Engineers of future AI systems might need to spend as much time testing how well they play with humans as on adding to their electronic IQs.

Robotic Process Automation

Sounds boring, right? Actually for the average web user or business, it’s way more important than machine learning. RPA refers basically to software tools for automating the “long tail” of mundane tasks that are boring, repetitive, and prone to human error. Every office — indeed everyone who uses a computer for work — has tasks like this.

Mac users have lots of these tools available. I use Textexpander, for example, to create a small three-character code which, when activated, can type a signature at the foot of an email, or the top of a letterhead or, for that matter, an entire page of stored boilerplate text. For other tasks there are tools like IFTTT, Apple’s Shortcuts and other automation tools that are built into the OS X operating system.

Windows users, however, were not so lucky, which I guess is why the WinAutomation tools provided by a British company Softmotive were so popular. And guess what? Softmotive has just been bought by Microsoft. Smart move by Redmond.

Quarantine diary — Day 61

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if your decide that your inbox is full enough already!