It might come to that yet. Some of the largest producers of wheat and rice, namely Kazakhstan and Vietnam, have suspended exports. This suggests that they may be anticipating severe disruption to their domestic supplies. The UK imports 50% of some of the foodstuffs we consume.

Sure, the lockdown saves lives that might otherwise be lost to Covid-19. But what about the avoidable deaths it might also be causing?

Fraser Nelson, the Editor of The Spectator has a startling article in today’s Daily Telegraph about the other side of social distancing and self-isolation. Here’s the core bit that struck me:

Matt Hancock, the Health Secretary, had been working with the Prime Minister on the next step: how to stop the end of lockdown being seen as a question of “lives vs money”. As a former economic adviser, Hancock is certainly mindful of the money: a £200 billion deficit could mean another decade of austerity. But other figures – infections, mortality rates and deaths – are rightly holding the national attention. Phasing out the lockdown needs to be spoken about in terms of lives vs lives. Or, crudely, whether lockdown might end up costing more lives than the virus.

Chris Whitty, the chief medical officer, has worried about this from the offset. In meetings he often stresses that a pandemic kills people directly, and indirectly. A smaller economy means a poorer society and less money for the NHS – eventually. But right now, he says, there will be parents avoiding the NHS, not vaccinating their children – so old diseases return. People who feel a lump now may not get it checked out. Cancer treatment is curtailed. Therapy is abandoned.

Work is being done to add it all up and produce a figure for “avoidable deaths” that could, in the long-term, be caused by lockdown. I’m told the early attempts have produced a figure of 150,000, far greater than those expected to die of Covid.

Nelson is pretty well-connected, so there might be something in this. And, as he points out, all of these numbers come from modelling studies, so should be treated cautiously. But, he says, estimates of lockdown victims are being shared among those in government who worry about the social damage now underway: the domestic violence, the depression, even suicides accompanying the mass bankruptcies. But since these are deaths that may, or may not, show up in national figures in a year’s time, it’s hard to weigh them up against a virus whose victims are being counted every day.

What all of this says to me is that the only reasonable way forward is gradual easing accompanied by dramatic increases in the production of N95 masks.

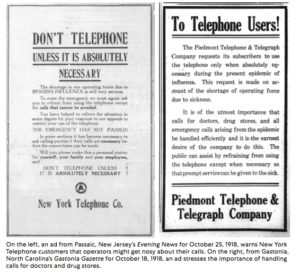

“War” is the wrong framing for this crisis

I’m as remiss as everyone else in thinking about the current crisis as a ‘war’ against the virus. So one resolution I’ve made today is to avoid using the metaphor in future.

Of course some of the measures now in force in the UK and elsewhere are reminiscent of ‘real’ wartime (e.g. 1939-1946). The burgeoning political talk about an “exit strategy” is likewise misleading, because it implies that, one day, victory over the virus will be achieved. In that sense it’s a bit like the so-called ‘war on terror’, which is really a war on an idea — and therefore never-ending.

There is no end to this, because the virus is a product of nature, and nature will be around long after humans have disappeared from the earth.

Besides, if the virus is an adversary, then it seems to hold most of the cards. It has reduced us to huddling in our caves, for example, while it does its own thing regardless. The human delusion of ‘taming’ nature was always hubris. Now we’re coming to terms with the inevitable nemesis.

And of course this is a tea-party compared to climate change.

Quarantine reading: Emily Wilson

The TLS has a nice compendium of what its various writers and reviewers are reading under lockdown. I was struck by this passage from Emily Wilson’s notes:

In my minimal work time, I am engaged in my translation of the Iliad. I’m now in the throes of Book 5, in which Diomedes confronts the gods on the battlefield. The idea of theomachy – in which a mortal human being grapples with immortal, unkillable, superhuman forces – takes on a new resonance now that far-shooting Apollo, god of plague, has afflicted our world with Covid-19. I began working on this translation at a time when the theme of sudden premature violent death, afflicting vast numbers of the population and bringing down prosperous cities and cultures, seemed relatively distant from my lived reality. Now, I feel haunted in new ways by the poem’s awareness that people can die far from home, far from their loved ones; that wealthy, beautiful, successful cities can be totally destroyed; that the squabbles of a privileged few can cost numberless people their lives, as well as their culture’s prosperity. It isn’t escapism, but there is a kind of comfort in the sense of being in an imaginary poetic landscape that feels so heartbreaking, so human and so truthful.

ps: Her translation of the Odyssey is terrific.

Why learning from other people’s mistakes is a useful skill

Lovely post by Alex Tabarrok.

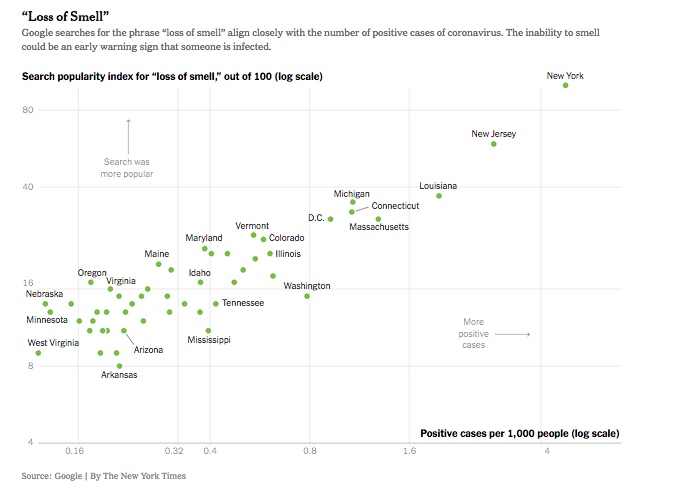

People get good at something when they have repeated attempts and rapid feedback. People can get pretty good at putting a basketball through a hoop. But for other decisions we only get one shot. One reason South Korea, Hong Kong and Taiwan have been much better at handling coronavirus is that within recent memory they had the SARS and H1N1 flu pandemics to build experience. The US and Europe were less hit by these earlier pandemics and responded less well. We don’t get many attempts to respond to once-in-a-lifetime events.

Even as coronavirus swept through China and Italy, many people dismissed the threat by thinking that we were somehow different. We weren’t. Even within the United States some people think that New York is different. It’s not. Most people learn, if they learn at all, from their own experiences, not from the experiences of others–even others like them. Learning from your own mistakes and experiences is a good skill. Many people make the same mistakes over and over again. But learning from other people’s mistakes or experiences is a great skill of immense power. It’s rare. Cultivate it.

The Zoombot arrives

It’s possible to have too much of a good thing. Already people working from home have discovered that they have too many Zoom meetings. The bad habits of organizations — especially their addiction to meetings — is being replicated online. I know people who have been online all week and have decided to have nothing to do with screens over this holiday weekend.

But help is at hand. Popular Mechanics reports that Matt Reed, a technologist at redpepper, a marketing design firm in Nashville, has created an AI-powered “Zoombot” that can sit in on video calls for you.

It all began when he noticed someone on Twitter (jokingly) complaining they don’t have time to go outside anymore because they’re always on Zoom calls.

“I was thinking, ‘How can I get someone out of this? What if you need to take a bathroom break, or you want to take a walk during a one-hour conference call? I wanted to find a funny take. We try not to take ourselves too seriously [at redpepper] but we still like to show what’s possible.”

For now, the project is tongue-in-cheek; Reed’s doppelgänger is a little slow to respond, doesn’t really blink, and uses a robotic voice similar to voice assistants like Siri or Alexa. But the code’s up on Github, so it’ll get smarter quickly. Stay tuned.

It’s the kind of thing that restores one’s faith in humanity.