“Algorithms do not have ethics, moral, values or ideologies, but people do. Questions about the ethics of AI are questions about the ethics of the people who make it and put it to use.”

Monthly Archives: May 2019

Sit here to think

So what took the establishment so long to get it?

From today’s Guardian:

Rising inequality in Britain risks putting the country on the same path as the US to become one of the most unequal nations on earth, according to a Nobel-prize winning economist.

Sir Angus Deaton is leading a landmark review of inequality in the UK amid fears that the country is at a tipping point due to a decade of stagnant pay growth for British workers. The Institute for Fiscal Studies thinktank, which is working with Deaton on the study, said the British-born economist would “point to the risk of the UK following the US” which has extreme inequality levels in pay, wealth and health.

Speaking to the Guardian at the launch of the study, he said: “There’s a real question about whether democratic capitalism is working, when it’s only working for part of the population.

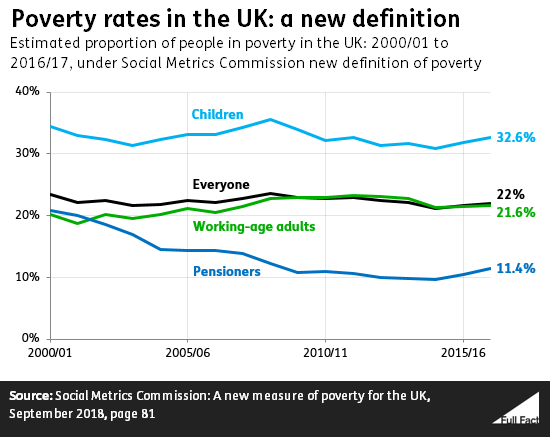

It’s only working for some people. This is a rich country, yet a significant proportion of its population (and, more importantly, their children) are living in poverty. (which, among other things, may help to explain the Brexit vote.)

Regulating the tech giants

This from Benedict Evan’s invaluable newsletter, written in response to Chris Hughes’s long NYT OpEd arguing that Facebook should be broken up…

I think there are two sets of issues to consider here. First, when we look at Google, Facebook, Amazon and perhaps Apple, there’s a tendency to conflate concerns about the absolute size and market power of these companies (all of which are of course debatable) with concerns about specific problems: privacy, radicalization and filter bubbles, spread of harmful content, law enforcement access to encrypted messages and so on, all the way down to very micro things like app store curation. Breaking up Facebook by splitting off Instagram and WhatsApp would reduce its market power, but would have no effect at all on rumors spreading on WhatsApp, school bullying on Instagram or abusive content in the newsfeed. In the same way, splitting Youtube apart from Google wouldn’t solve radicalization. So which problem are you trying to solve?

Second, anti-trust theory, on both the diagnosis side and the remedy side, seems to be flummoxed when faced by products that are free or as cheap as possible, and that do not rely on familiar kinds of restrictive practices (the tying of Standard Oil) for their market power. The US in particular has tended to focus exclusively on price, where the EU has looked much more at competition, but neither has a good account of what exactly is wrong with Amazon (if anything – and of course it is still less than half the size of Walmart in the USA), or indeed with Facebook. Neither is there a robust theory of what, specifically, to do about it. ‘Break them up’ seems to come more from familiarity than analysis: it’s not clear how much real effect splitting off IG and WA would have on the market power of the core newsfeed, and Amazon’s retail business doesn’t have anything to split off (and no, AWS isn’t subsidizing it). We saw the same thing in Elizabeth Warren’s idea that platform owners can’t be on their own platform – which would actually mean that Google would be banned from making Google Maps for Android. So, we’ve got to the point that a lot of people want to do something, but not really, much further.

This is a good summary of why the regulation issue is so perplexing. Our difficulties include the fact that we don’t have an analytical framework yet for (i) analysing the kinds of power wielded by the platforms; (ii) categorising the societal harms which the tech giants might be inflicting; or (iii) understanding how our traditional toolset for dealing with corporate power (competition law, antitrust, etc.) needs to be updated for the contemporary challenges posed by the companies.

Just after I’d read the newsletter, the next item in my inbox contained a link to a Pew survey which revealed the colossal numbers of smartphone users across the world who think they are accessing the Internet when they’re actually just using Facebook or WhatsApp. Interestingly, it’s mostly those who have some experience of hooking up to the Internet via a desktop PC who know that there’s actually a real Internet out there. But if your first experience of Internet connectivity is via a smartphone running the Facebook app (which means that your data may be free), then as far as you are concerned, Facebook is the Internet.

So Facebook has, effectively, blotted out the open Internet for a large segment of humanity. That’s also a new kind of power for which we don’t have — at the moment — a category. Just as the so-called Right to be Forgotten* recognises that Google has the power to render someone invisible. After all, in a networked world, if the dominant search engine doesn’t find you, then effectively you have ceased to exist.

- It’s not a right to be forgotten, merely a right not to be found by Google’s search engine. The complained-of information remains on the website where it was originally published.

How Microsoft reinvented itself

This morning’s Observer column:

It may have escaped your attention, but Microsoft recently became the third company in history to reach a valuation of one trillion dollars. To which the standard reaction, I have discovered, is: “Eh? Microsoft!!!” Wasn’t that the boring old monolith fixated on desktop products and operating systems that missed out on the smartphone revolution? The company that Bill Gates used to run before he decided to devote himself full-time to giving his money away? The company whose Exchange Server is the bane of every office-worker’s daily grind? The ruthless monopolist who missed the world wide web and then set out to exterminate the one company – Netscape – that hadn’t?

Yes, that Microsoft. Given the company’s history, this is surely the greatest comeback since Lazarus. But with one difference: where Lazarus’s resurrection was (according to the New Testament) instantaneous, Microsoft’s took longer. How this happened is a story that will keep MBA students occupied for decades, but with the benefit of hindsight, we can now see that it has three main strands…

The truth about Ansel Adams

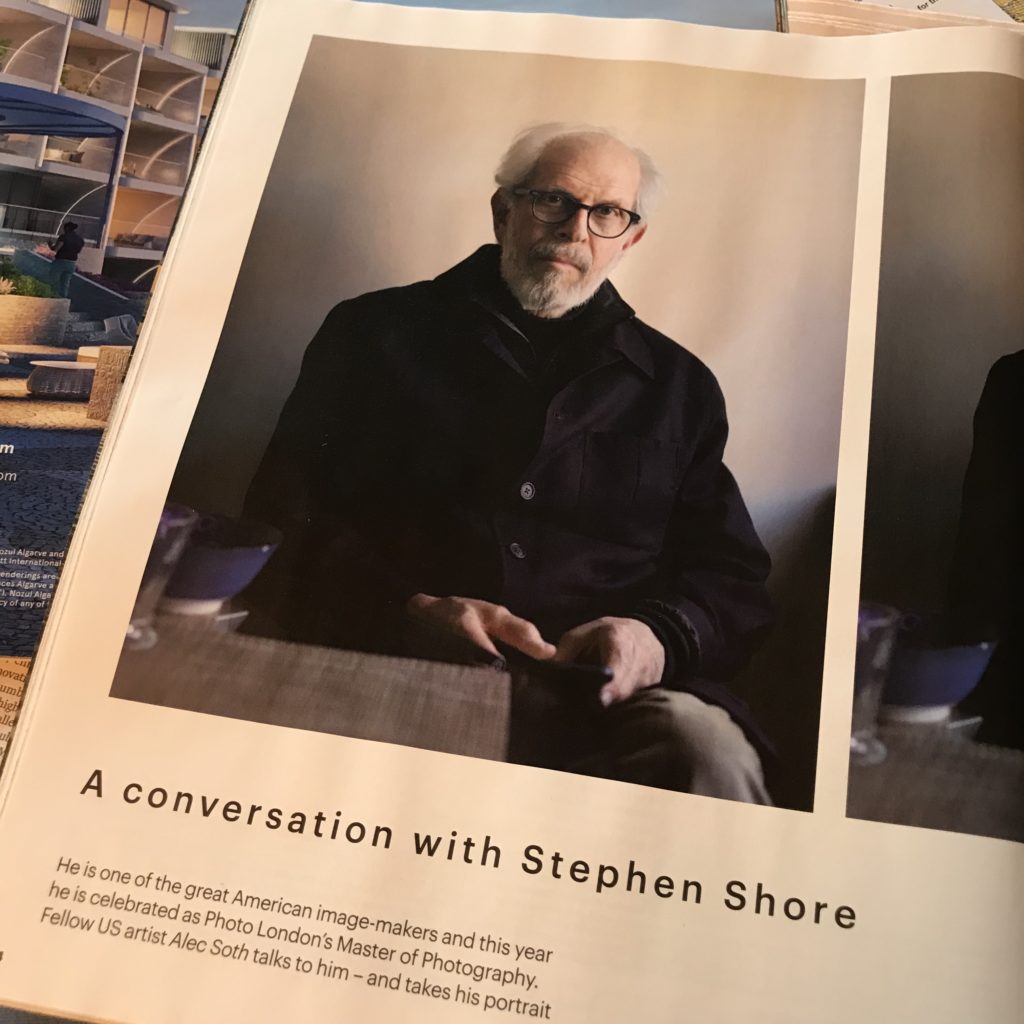

There’s an interesting interview of the photographer Stephen Shore by another photographer, Alec Soth, in today’s Financial Times. It contains an interesting story about Shore’s first encounter with Ansel Adams:

One of my closest friends at the time was a curator named Weston Naef, and he had a loft in SoHo. He invited me to dinner one night with Ansel Adams. This is in maybe the mid-1970s. Ansel had been, in fact, very helpful to me without my knowing it. Uncommon Places [Shore’s first book] came about because I had a show in ’76 at MoMa and he saw it and came back with his editor at New York Graphic Society, named Tim Hill, and suggested they do a book. That’s how Uncommon Places happened.

Ansel had been drinking before I got there, and while I was there he had six glasses of straight vodka — a prodigious amount of vodka — and at one point he said, “I had a creative hot streak in the ’40s, and since then I’ve been pot-boiling.” And I thought, when I’m 85 that’s not how I want to look back at my life.

Later in the conversation he asks Adams how he managed to do as much work as he had in the 1940s when he had five children. The reply: “I got separated”. I’m reminded of Cyril Connolly’s listing of “the pram in the hall” as one of his Enemies of Promise.

So there is a God, after all

One of the things that cheered me up no end this weekend was the way Uber’s IPO flopped — at least in comparison with the $120B fantasies of the punters who had invested in it on the assumption that it would be the winner-that-took-all in the market for mobility. The assumption of the company was that it wold be valued at $100B at the IPO, but in fact it wound up at $70B. Which means that a significant number of investors are probably left owning shares that are worth less than they paid for them in more recent funding rounds. Since the Saudi royals are among those investors, it couldn’t have happened to nastier people.

Sixty years on

Today is the 60th anniversary of CP Snow’s celebrated Rede Lecture on the Two Cultures, which started an argument that sometimes rages still. Tim Harford has a nice essay marking the anniversary. Sample:

Snow was on to something important. His message was garbled, in fact, because he was on to several important things at once. The first is the challenge of collaboration. If anything, The Two Cultures understates that. Yes, the classicists need to work with the scientists, but the physicists also need to work with the biologists, the economists must work with the psychologists, and everyone has to work with the statisticians. And the need for collaboration between technical experts has grown over time because, as science advances and problems grow more complex, we increasingly live in a world of specialists.

The economist Benjamin Jones has been studying this issue by examining databases of patents and scientific papers. His data show that successful research now requires larger teams filled with more specialised researchers. Scientific and material progress demands complex collaboration.

Snow appreciated — in a way that many of us still do not — how profound that progress was. The scientist and writer Stephen Jay Gould once mocked Snow’s prediction that “once the trick of getting rich is known, as it now is, the world can’t survive half rich and half poor” and that division would not last to the year 2000. “One of the worst predictions ever printed,” scoffed Gould in a book published posthumously in 2003.

Had Gould checked the numbers, he would have seen that between 1960 and 2000, the proportion of people living in extreme poverty had roughly halved, and it has continued to fall sharply since then. Snow’s 40-year forecast was more accurate than Gould’s 40 years of hindsight. Even when we fancy ourselves broadly educated, as Gould did, we may not know what we don’t know. That was one of Snow’s points.

But the deepest point of all — buried a little too deep, perhaps — is a practical problem that remains as pressing today as it was in 1959: how to reconcile technical expertise with the demands of policy and politics. In short — have we really had enough of experts?

The historian Lisa Jardine highlights this sentence in Snow’s argument: “It is the traditional culture, to an extent remarkably little diminished by the emergence of the scientific one, which manages the western world.” We didn’t decide we’d had enough of experts in 2016; we made that decision long ago.

Cambridge University Press published a nice anniversary edition of the lectures a while back, with a wonderful introductory essay by Stefan Collini.

In some ways, Snow was a sad — and sometimes a ponderous — figure. I met him once. I was writing a profile of Solly Zuckerman at the time and went to see him in his office in London (he was an official in Harold Wilson’s administration). I found him to be helpful and generous with his time.

The technical is political. Now what?

Bruce Schneier has been valiantly going on about this for a while. Once upon a time, digital technology didn’t have many social, political or democratic ramifications. Those days are over. Universities, companies, software engineers and governments need to think about this — and tool up for it. Here’s an excerpt from one of Bruce’s recent posts on the subject:

Technology now permeates society in a way it didn’t just a couple of decades ago, and governments move too slowly to take this into account. That means technologists now are relevant to all sorts of areas that they had no traditional connection to: climate change, food safety, future of work, public health, bioengineering.

More generally, technologists need to understand the policy ramifications of their work. There’s a pervasive myth in Silicon Valley that technology is politically neutral. It’s not, and I hope most people reading this today knows that. We built a world where programmers felt they had an inherent right to code the world as they saw fit. We were allowed to do this because, until recently, it didn’t matter. Now, too many issues are being decided in an unregulated capitalist environment where significant social costs are too often not taken into account.

This is where the core issues of society lie. The defining political question of the 20th century was: “What should be governed by the state, and what should be governed by the market?” This defined the difference between East and West, and the difference between political parties within countries. The defining political question of the first half of the 21st century is: “How much of our lives should be governed by technology, and under what terms?” In the last century, economists drove public policy. In this century, it will be technologists.

The future is coming faster than our current set of policy tools can deal with. The only way to fix this is to develop a new set of policy tools with the help of technologists. We need to be in all aspects of public-interest work, from informing policy to creating tools all building the future. The world needs all of our help.

Yep.

What Trump doesn’t know

From Kara Swisher:

I’m sorry to be the one to have to tell the president, but someone has to: Social media is not the public square, not even a virtual one.

Not Facebook. Not Reddit. Not YouTube. And definitely not Twitter, where a few days after Facebook announced it was barring some extremist voices like Alex Jones, President Trump furiously tapped out: “I am continuing to monitor the censorship of AMERICAN CITIZENS on social media platforms. This is the United States of America — and we have what’s known as FREEDOM OF SPEECH! We are monitoring and watching, closely!!”

He can monitor (yes, that’s definitely a creepy word) and watch all he wants, but it will not matter one bit. Because the First Amendment requires only that the government not make laws that restrict freedom of speech for its citizens…