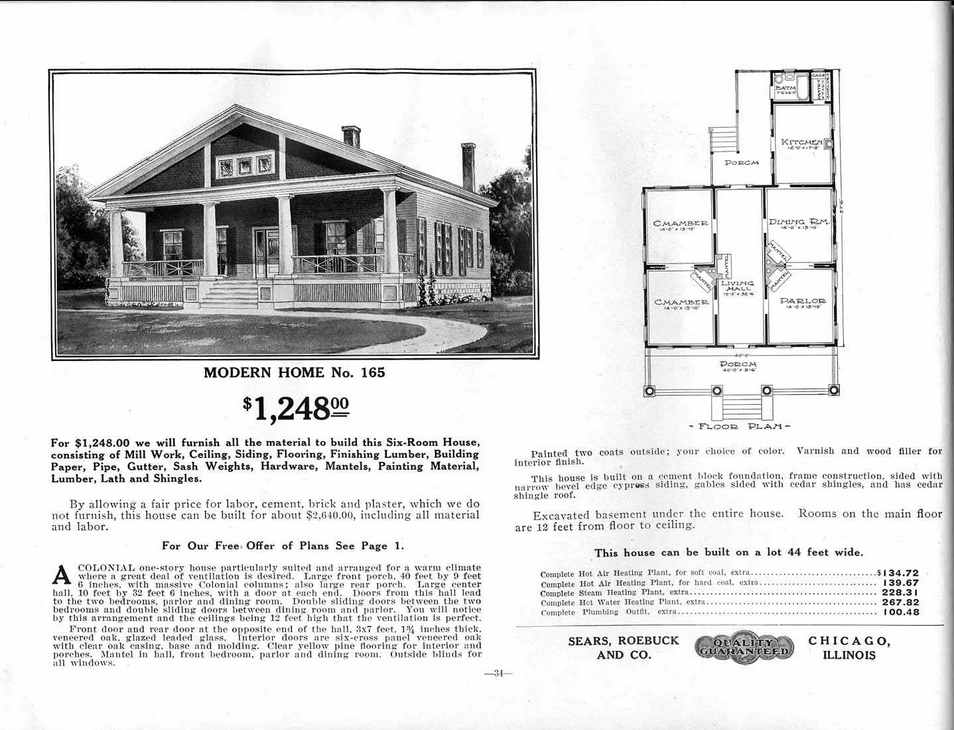

The New York Times today reports that Sears, which more than a century ago pioneered the strategy of selling everything to everyone, filed for bankruptcy protection early on Monday. In terms of ambition, its only rival is Amazon, but even Amazon hasn’t yet got round to selling houses in kit form, as Sears did as long ago as 1908. Here’s one from the catalogue: two bedrooms, two reception rooms, a kitchen and a splendid porch — yours for $1248.00. No mention of a bathroom, though.

Monthly Archives: October 2018

The cost of insecurity (not to mention of Windows XP)

From The Inquirer:

THE WANNACRY RANSOMWARE ATTACK cost the already cash-strapped NHS almost £100m, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) estimates.

Until now, the financial damage caused by the sweeping cyber attack – which it’s now been revealed affected 8 per cent of GP clinics and forced the NHS to cancel 19,000 appointments – has been unclear, but the DHSC estimates in a new report that the total figure cost in at £92m.

WannaCry cost approximately £19 in lost output, while a whopping £73m was racked up in IT costs in the aftermath of the attack, according to the report. Some £72m was spent on restoring systems and data in the weeks after the attack struck.

“We recognise that at the time of the attack the focus would have been on patient care rather than working out what WannaCry was costing the NHS,” the report says.

Following the attack, the NHS has pledged to upgrade all of its systems to Windows 10 after it was found that the service’s outdated, and unpatched Windows XP and Windows 7 systems were largely to blame.

Dinner-table capital

Well, well. This from the Sloan School at MIT:

A new study shows that, thanks to inequality, the U.S. has potentially missed out on millions of inventors during that time — what the researchers refer to as “lost Einsteins.” Kids born into the richest 1 percent of society are 10 times more likely to be inventors than those born into the bottom 50 percent — and “this is having a big effect on innovation,” MIT Sloan professor John Van Reenen said.

The research also shows that innovation in the U.S. could quadruple if women, minorities, and children from low-income families became inventors at the same rate as men from high-income families. Making that happen is the hard part, though. It means exposing more children to innovation when they are young — and the younger they are, the better.

The researchers wanted to see what part childhood wealth plays on future innovation. And guess what? “The most striking thing was how sharp the relationship was between the wealth of your parents and whether you grew up to be an inventor or not” reported one of the researchers.

By linking patent records with de-identified IRS data and school district records for more than one million inventors, the researchers found that, while ability does play some part in a child’s chance of becoming an inventor in the future, it is far from the biggest factor.

Instead, wealth played a much larger role. Among children who excelled in math in third grade, those whose families’ incomes fell into the highest fifth of the population were more than five times as likely to be inventors than those whose families’ incomes were in the lowest fifth.

This disparity is amplified among children whose parents were in the top 1 percent of earners — they were 10 times more likely to be inventors than those in the bottom 50 percent.

Oh – and white children were three times as likely as black children to be inventors. And only 18 percent of inventors were women.

Why digital tech might not be the key to development for poor countries

Interesting essay by Dani Rodrik:

Any optimism about the scale of GVCs’ contribution must be tempered by three sobering facts. First, the expansion of GVCs seems to have ground to a halt in recent years. Second, developing-country participation in GVCs – and indeed in world trade in general – has remained quite limited, with the notable exception of certain Asian countries. Third, and perhaps most worrisome, the domestic employment consequences of recent trade and technological trends have been disappointing.

Upon closer inspection, GVCs and new technologies exhibit features that limit the upside to – and may even undermine – developing countries’ economic performance. One such feature is an overall bias in favor of skills and other capabilities. This bias reduces developing countries’ comparative advantage in traditionally labor-intensive manufacturing (and other) activities, and decreases their gains from trade.

Second, GVCs make it harder for low-income countries to use their labor-cost advantage to offset their technological disadvantage, by reducing their ability to substitute unskilled labor for other production inputs. These two features reinforce and compound each other. The evidence to date, on the employment and trade fronts, is that the disadvantages may have more than offset the advantages.

The usual response to these concerns is to stress the importance of building up complementary skills and capabilities. Developing countries must upgrade their educational systems and technical training, improve their business environment, and enhance their logistics and transport networks in order to make fuller use of new technologies, goes the oft-heard refrain.

And here’s the punchline:

But pointing out that developing countries need to advance on all those dimensions is neither news nor helpful development advice. It is akin to saying that development requires development. Trade and technology present an opportunity when they are able to leverage existing capabilities, and thereby provide a more direct and reliable path to development. When they demand complementary and costly investments, they are no longer a shortcut around manufacturing-led development.

Great essay.

Facebook: another routine scandal

From today’a New York Times:

SAN FRANCISCO — On the same day Facebook announced that it had carried out its biggest purge yet of American accounts peddling disinformation, the company quietly made another revelation: It had removed 66 accounts, pages and apps linked to Russian firms that build facial recognition software for the Russian government.

Facebook said Thursday that it had removed any accounts associated with SocialDataHub and its sister firm, Fubutech, because the companies violated its policies by scraping data from the social network.

“Facebook has reason to believe your work for the government has included matching photos from individuals’ personal social media accounts in order to identify them,” the company said in a cease-and-desist letter to SocialDataHub that was dated Tuesday and viewed by The New York Times.

Piketty: our politics is now about Brahmin vs Merchant elites

Fascinating paper by Thomas Piketty. He constructs a long-run data series from post-election to document a striking long-run evolution in the multi-dimensional structure of political cleavages in the US, UK and France.

The nub of it is this:

In the 1950s-1960s, the vote for “left-wing” (socialist-labour-democratic) parties was associated with lower education and lower income voters. This corresponds to what one might label a “class-based” party system: lower class voters from the different dimensions (lower education voters, lower income voters, etc.) tend to vote for the same party or coalition, while upper and middle class voters from the different dimensions tend to vote for the other party or coalition.

Since the 1970s-1980s, “left-wing” vote has gradually become associated with higher education voters, giving rise to what I propose to label a “multiple-elite” party system in the 2000s-2010s: high- education elites now vote for the “left”, while high-income/high-wealth elites still vote for the “right” (though less and less so) — i.e. the “left” has become the party of the intellectual elite (Brahmin left), while the “right” can be viewed as the party of the business elite (Merchant right).

I show that the same transformation happened in France, the US and Britain, despite the many differences in party systems and political histories between these three countries.

This links to the observations of Daniel Rodgers summarised below.

Sometimes, it’s the data you’re missing that’s the key to understanding something

Nice salutary tale for data fiends:

How Not to Be Wrong opens with an extremely interesting tale from World War II. As air warfare gained prominence, the challenge for the military was figuring out where and in what amount to apply protective armor to fighter planes and bombers. Apply too much armor and the planes become slower, less maneuverable and use more fuel. Too little armor, or if it’s in the “wrong” places, and the planes run a higher risk of being brought down by enemy fire.

To make these determinations, military leaders examined the amount and placement of bullet holes on damaged planes that returned to base following their missions. The data showed almost twice as much damage to the fuselage of the planes compared to other areas, most specifically the engine compartments, which generally had little damage. This data led the military leaders to conclude that more armor needed to be placed on the fuselage.

But mathematician Abraham Wald examined the data and came to the opposite conclusion. The armor, Wald said, doesn’t go where the bullet holes are; instead, it should go where the bullet holes aren’t, specifically, on the engines. The key insight came when Wald looked at the damaged planes that returned to the base and asked where all the “missing” bullet holes to the engines were. The answer was the “missing” bullet holes were on the missing planes, i.e. the ones that didn’t make it back safely to base. Planes that got hit in the engines didn’t come back, but those that sustained damage to the fuselage generally could make it safely back. The military then put Wald’s recommendations into effect and they stayed in place for decades.

The great Chinese hardware hack: true or false?

This morning’s Observer column:

On 4 October, Bloomberg Businessweek published a major story under the headline “The Big Hack: How China Used a Tiny Chip to Infiltrate US Companies”. It claimed that Chinese spies had inserted a covert electronic backdoor into the hardware of computer servers used by 30 US companies, including Amazon and Apple (and possibly also servers used by national security agencies), by compromising America’s technology supply chain.

According to the Bloomberg story, the technology had been compromised during the manufacturing process in China. Undercover operatives from a unit of the People’s Liberation Army had inserted tiny chips – about the size of a grain of rice – into motherboards during the manufacturing process.

The affected hardware then made its way into high-end video-compression servers assembled by a San Jose company called Supermicro and deployed by major US companies and government agencies…

The task facing liberals now

This from a very perceptive essay by Daniel Rodgers:

More realistically, liberals must find ways to win back some of those who swung to Donald Trump’s camp. Populists, the press routinely calls them. But aside from their distrust of distant experts and cosmopolitan elites, Trump’s core voters have little in common politically with the People’s Party of the American 1890s. The 1890s Populists, like today’s Trump supporters, sometimes fell for terribly oversimplified answers. But the Populists hurled their political fury at the forces of organized money: the bankers, the monopolists, the railroad magnates, and the politicians who wrote the back-room deals of the money-men into law. The conviction that powers Trump voters’ imaginations is just the reverse. Theirs is a world in which not capitalist institutions but the political establishment hogs the seats of power. In their minds, government rigs the game for its own advantages, tying up the potential expansive force of business with rules that only serve to keep the regulators in jobs and the poor as their clients. Only through this story is it possible to redirect anger at plant closings from the corporations who order them to the liberal establishment that is said to be covertly responsible.

Amazon’s minimum wage

Interesting commentary by Alex Tabarrok:

Amazon’s widely touted increase in its minimum wage was accompanied by an ending of their monthly bonus plan, which often added 8% to a worker’s salary (16% during holiday season), and its stock share program which recently gave workers shares worth $3,725 at two years of employment. I’m reasonably confident that most workers will still benefit on net, simply because the labor market is tight, but it’s clear that the increase in the minimum wage was not as generous as it first appeared…

Worth reading in full.