Le Quatorze Juillet!

In pre-pandemic times, we’d be there today. Sigh.

Notes from the new battleground

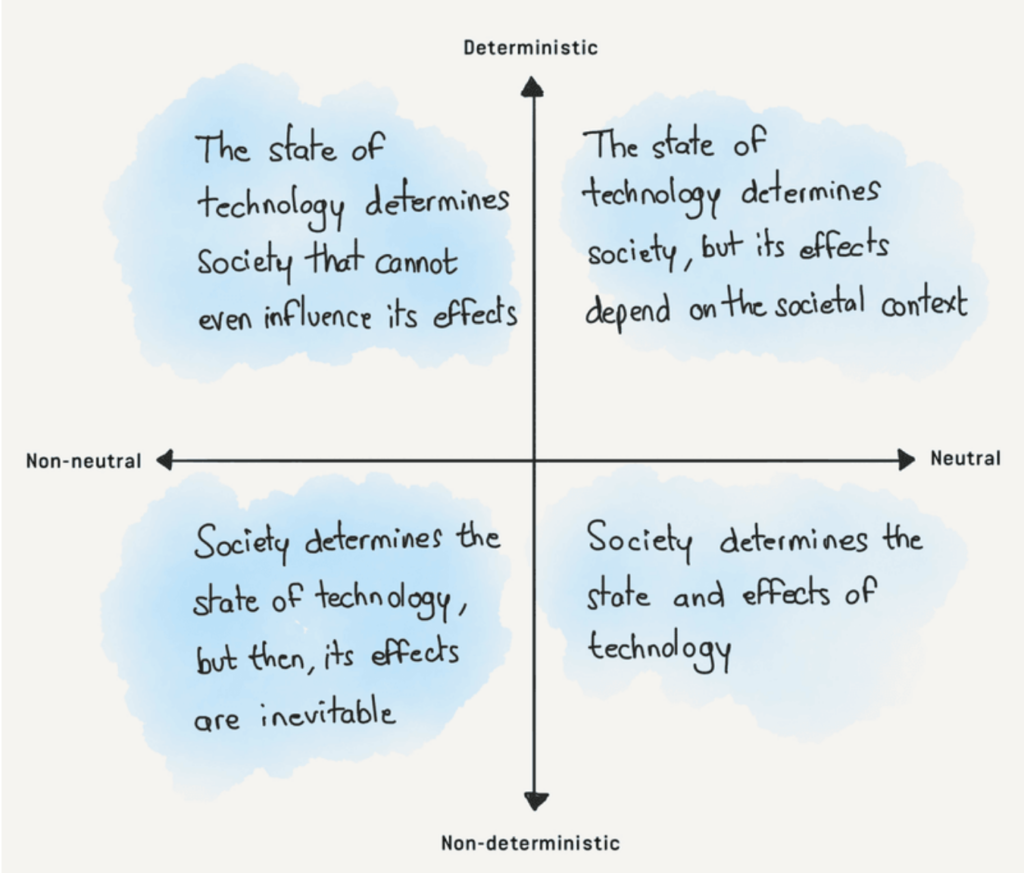

Cyberspace viewed through a military lens.

1/ The Internet is now the dominant communications medium of our world. And we’re still only at the beginning of that transformation.

2/ The network is now a battlefield, indispensable to militaries and their governments.

3/ This changes how conflicts are being — and will be — fought.

- It’s now impossible to keep secrets

- Power becomes the ability to command people’s attention

- Conflicts become “contests of psychological and algorithmic manipulation.”

4/ The nature of ‘war’ is changing. It used to be “the continuation of politics by other means”. But now war and politics have begun to fuse together. However the laws of this new battlefield are not formulated by democratic or military authorities but by a handful of American tech companies.

5/ And we’re all caught up in this new warfare, as combatants, spectators or collateral damage. Our attention has become a piece of contested territory “being fought over in conflicts that you may or may not realise are unfolding around you. Your online attention and actions are thus both targets and ammunition in an unending series of skirmishes. Whether you have an interest in the conflicts of ‘Likewar’ or not, they have an interest in you”.

Notes from reading Likewar: The Weaponization of Social Media by P.W. Singer and Emerson Brooking, Houghton Mifflin, 2018.

The dark underbelly of ‘efficiency’

Tim Bray, one of the most thoughtful geeks around, has an interesting essay on his blog about the downsides of the neoliberal obsession with ‘efficiency’.

On a Spring 2019 walk in Beijing I saw two street sweepers at a sunny corner. They were beat-up looking and grizzled but probably younger than me. They’d paused work to smoke and talk. One told a story; the other’s eyes widened and then he laughed so hard he had to bend over, leaning on his broom. I suspect their jobs and pay were lousy and their lives constrained in ways I can’t imagine. But they had time to smoke a cigarette and crack a joke. You know what that’s called? Waste, inefficiency, a suboptimal outcome. Some of the brightest minds in our economy are earnestly engaged in stamping it out. They’re winning, but everyone’s losing.

I’ve felt this for years, and there’s plenty of evidence:

Item: Every successful little store with a personality morphs into a chain because that’s more efficient. The personality becomes part of the brand and thus rote.

Item: I go to a deli fifteen minutes away to buy bacon, rashers cut from the slab while I wait, because they’re better. Except when I can’t, in which case I buy a waterlogged plastic-encased product at the supermarket; no standing or waiting! It’s obvious which is more efficient.

Item: I’ve learned, when I have a problem with a tech vendor, to seek out the online-chat help service; there’s annoying latency between question and answers as the service rep multiplexes me in with lots of other people’s problems, but at least the dialog starts without endless minutes on hold; a really super-efficient process. Item: Speaking of which, it seems that when you have a problem with a business, the process for solving it each year becomes more and more complex and opaque and irritating and (for the business) efficient.

Item, item, item; as the world grows more efficient it grows less flavorful and less human. Because the more efficient you are, the less humans you need.

To help develop his argument, Bray links to a terrific essay by Bruce Schneier, my favourite security guru:

For decades, we have prized efficiency in our economy. We strive for it. We reward it. In normal times, that’s a good thing. Running just at the margins is efficient. A single just-in-time global supply chain is efficient. Consolidation is efficient. And that’s all profitable. Inefficiency, on the other hand, is waste. Extra inventory is inefficient. Overcapacity is inefficient. Using many small suppliers is inefficient. Inefficiency is unprofitable.

But inefficiency is essential security, as the COVID-19 pandemic is teaching us. All of the overcapacity that has been squeezed out of our healthcare system; we now wish we had it. All of the redundancy in our food production that has been consolidated away; we want that, too. We need our old, local supply chains — not the single global ones that are so fragile in this crisis. And we want our local restaurants and businesses to survive, not just the national chains.

We have lost much inefficiency to the market in the past few decades. Investors have become very good at noticing any fat in every system and swooping down to monetize those redundant assets. The winner-take-all mentality that has permeated so many industries squeezes any inefficiencies out of the system.

This drive for efficiency leads to brittle systems that function properly when everything is normal but break under stress. And when they break, everyone suffers. The less fortunate suffer and die. The more fortunate are merely hurt, and perhaps lose their freedoms or their future. But even the extremely fortunate suffer — maybe not in the short term, but in the long term from the constriction of the rest of society.

Efficient systems have limited ability to deal with system-wide economic shocks. Those shocks are coming with increased frequency. They’re caused by global pandemics, yes, but also by climate change, by financial crises, by political crises. If we want to be secure against these crises and more, we need to add inefficiency back into our systems.

Yep.

Bray ends with a protest:

It’s hard to think of a position more radical than being “against efficiency”. And I’m not. Efficiency is a good, and like most good things, has to be bought somehow, and paid for. There is a point where the price is too high, and we’ve passed it.

Actually, there are times when efficiency is not good but positively bad. Take our criminal justice system. It’s woefully inefficient because we have this commitment to ‘due process’, the presumption of innocence until guilt is proven, legal representation and the rest. It would be much more ‘efficient’ to be able to lock people up on the say-so of the local chief of police. But we don’t do that because our liberal, democratic values abhor it. (Which is also why authoritarians love it.) Of course the criminal justice system should operate more efficiently — in the sense that courts should be run so that the dispensation of justice is quicker and with less pointless delay, lower legal costs, etc. But the central inefficiency of the system implied by the need for due process is the most precious thing about it.

Tim Bray’s essay led me to David Wooton’s book, Power, Pleasure, and Profit: Insatiable Appetites from Machiavelli to Madison, and thence to his 2017 Besterman Lecture at Oxford, which is based on Chapter 8 of the book.

Link

I Have Cancer. Now My Facebook Feed Is Full of ‘Alternative Care’ Ads

Here we go again. Most of the current hoo-hah about Facebook and moderation is about politics and extremism. But actually almost every area of life is affected by the Facebook targeting system. Here’s a great example of that from the personal experience of Anne Borden King — who, ironically, is an advocate working to prevent the spread of medical misinformation online. “Last week”, she writes,

I posted about my breast cancer diagnosis on Facebook. Since then, my Facebook feed has featured ads for “alternative cancer care.” The ads, which were new to my timeline, promote everything from cumin seeds to colloidal silver as cancer treatments. Some ads promise luxury clinics — or even “nontoxic cancer therapies” on a beach in Mexico.

When I saw the ads, I knew that Facebook had probably tagged me to receive them. Interestingly, I haven’t seen any legitimate cancer care ads in my newsfeed, just pseudoscience. This may be because pseudoscience companies rely on social media in a way that other forms of health care don’t. Pseudoscience companies leverage Facebook’s social and supportive environment to connect their products with identities and to build communities around their products. They use influencers and patient testimonials. Some companies also recruit members through Facebook “support groups” to sell their products in pyramid schemes.

Anyone who has experimented with using Facebook’s advertising system will not be surprised by her experience. What happened is that people flogging snake oil were using Facebook’s automated machine for helping them to build a “custom audience”, and one of the questions the system will have asked them is whether they would like to target people who have posted that they have had a cancer diagnosis. Click yes and it’s done.

Finally: the UK government is mandating the wearing of face masks

This is how Politico’s daily ‘London Playbook’ newsletter puts it.

Health and Social Care Secretary Matt Hancock will give a statement in the House of Commons this afternoon confirming the news on every front page this morning: face coverings will be compulsory in shops and supermarkets in England from Friday July 24, with those refusing to wear them facing fines of up to £100.

What took you so long? The British Medical Association last night called the announcement — which brings England in line with Scotland Germany, Spain, Italy and Greece and many other countries — “long overdue,” and called for the regulation to be extended to all settings where social distancing is not possible. BMA council Chair Dr Chaand Nagpaul also questioned why the government was waiting 10 days to implement the policy. “Each day that goes by adds to the risk of spread and endangers lives,” he said. Officials say the delay will give businesses and the public time to prepare. Retailers won’t be expected to enforce the new regulations, which will be a matter for police. Only children under 11 and those with certain disabilities will be exempt.

We’ve come a long way since … the received wisdom in the U.K. was that mass wearing of face masks did little or nothing to help. It’s just over 100 days, for instance, since England’s Deputy Chief Medical Officer Jonathan Van-Tam said at the Downing Street lectern on April 3: “There is no evidence that general wearing of the face masks by the public who are well affects the spread of the disease.”

We’ve not come very far at all since … Cabinet Office Minister Michael Gove, when asked by the the BBC’s Andrew Marr whether face masks should be mandatory in shops in England, said: “I don’t think mandatory, no.” It’s not yet been 48 hours.

Nothing changes. The UK government couldn’t run a bath.

(The Politico newsletter is indispensable IMHO. And it’s free. First thing I read every morning.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!