If you need cheering up, how about this?

One of the great comedians of his generation. I love his epitaph: “I told you I was ill”.

Politico’s daily summary

One of the joys (well, sometimes) of my early morning is finding Politico’s daily London Playbook (i.e. newsletter) by Jack Blanchard in my inbox. This is how it opens today:

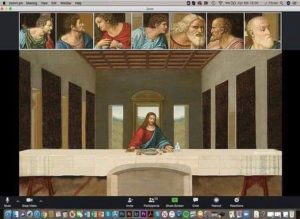

THEY’RE BACK! Parliament returns today from its extended Easter recess to lead a country utterly changed from just one month before. When the House rose on March 25, Britain had been in lockdown for less than 48 hours, and fewer than 500 U.K. citizens had died from COVID-19. Boris Johnson was still running the country and a picture of jovial health; Jeremy Corbyn was leader of the opposition and taking part in his final PMQs. The Premier League was due to resume from its brief hiatus on April 30, and most people thought “Zoom” was an ice lolly from 1986.

Fast-forward 4 weeks … and Zoom has become such a crucial part of our lives that MPs will be using it to hold debates in the Commons chamber as of tomorrow. More than 16,500 Britons have died from the illness; a fierce debate is underway about when to lift a lockdown now destroying the U.K. economy; Johnson is recuperating at Chequers after almost losing his life to COVID-19, and Keir Starmer is leading a Labour Party already plunged into fresh civil war. Dominic Raab has the nuclear codes in his pocket; Liverpool’s title charge has been suspended indefinitely, and NHS nurses have been dressing in bin bags after supplies of protective kit ran out. So MPs shouldn’t be short of things to talk about when proceedings get underway.

If you’re a politics junkie you can subscribe here

Zoom’s security woes were no secret to business partners like Dropbox

Well, well. On the day that the UK House of Commons ‘returns’ using Zoom (the House of Lords is apparently going to use a Microsoft system), the New York Times reports that Dropbox became so concerned about Zoom’s security holes that the company commissioned a number of hackers to find the holes, which they then reported to Zoom.

Zoom’s defenders, including big-name Silicon Valley venture capitalists, say the onslaught of criticism is unfair. They argue that Zoom, originally designed for businesses, could not have anticipated a pandemic that would send legions of consumers flocking to its service in the span of a few weeks and using it for purposes — like elementary school classes and family celebrations — for which it was never intended.

“I don’t think a lot of these things were predictable,” said Alex Stamos, a former chief security officer at Facebook who recently signed on as a security adviser to Zoom. “It’s like everyone decided to drive their cars on water.”

Motherboard is reporting that there are currently two Zoom zero-day exploits, one for Windows and one for MacOS, on the market.

And there’s a report that over 500,000 Zoom accounts are being sold on the dark web and hacker forums for less than a penny each, and in some cases, given away for free.

But still…amphibious cars — now there’s a good idea!

Another previously-profitable business is suddenly defunct

The big in-person conferencing event is suddenly passé. As someone who has always loathed conferences, this troubles me not at all. But to those who are addicted to them, it’s obviously depressing news. Here’s one gloomy take on it all:

At the same time, it’s becoming increasingly clear that conferences won’t be returning to normal anytime soon. Mark Zuckerberg said Thursday that Facebook won’t host any events with 50 people or more until June 2021; Microsoft announced that it won’t be having in-person conferences until at least July 2021. California Gov. Gavin Newsom said this week that large gatherings in the state are “unlikely” until the availability of a coronavirus vaccine, and Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti suggested that his city won’t see large-scale events until 2021. Some in the tech industry are already predicting that CES in January will be canceled, as well.

Brightcove’s Larsen acknowledged that she wouldn’t send her own team members to in-person events right now, adding: “Until there is a vaccine that works, it is going to be really hard to get 10,000 people together in a space.”

The trouble is that while Zoom and streaming technology can replace some of what people get from in-person gatherings, there are still things that will be missing. As Ben Evans says in his current newsletter:

Conferences are a bundle: the content (which works as video, mostly), but also the chance meetings & networking, and the meetings you book because everyone’s in town, and sometimes also a trade fair, and none of those work as video, far less a random text chat room. And if you do switch the in-person meeting in a hotel room in that particular city to a video call from across the world, why do you need to do it on that particular date? There’s a second wave of products to be created here, I suspect.

America’s ‘underlying conditions’

Terrific, long essay by George Packer, whose book [The Unwinding: Thirty Years of American decline] (https://amzn.to/3eF7fc6) set the scene for what the country is now experiencing. This is how the essay begins:

When the virus came here, it found a country with serious underlying conditions, and it exploited them ruthlessly. Chronic ills—a corrupt political class, a sclerotic bureaucracy, a heartless economy, a divided and distracted public—had gone untreated for years. We had learned to live, uncomfortably, with the symptoms. It took the scale and intimacy of a pandemic to expose their severity—to shock Americans with the recognition that we are in the high-risk category.

The crisis demanded a response that was swift, rational, and collective. The United States reacted instead like Pakistan or Belarus—like a country with shoddy infrastructure and a dysfunctional government whose leaders were too corrupt or stupid to head off mass suffering. The administration squandered two irretrievable months to prepare. From the president came willful blindness, scapegoating, boasts, and lies. From his mouthpieces, conspiracy theories and miracle cures. A few senators and corporate executives acted quickly—not to prevent the coming disaster, but to profit from it. When a government doctor tried to warn the public of the danger, the White House took the mic and politicized the message.

Every morning in the endless month of March, Americans woke up to find themselves citizens of a failed state. With no national plan—no coherent instructions at all—families, schools, and offices were left to decide on their own whether to shut down and take shelter. When test kits, masks, gowns, and ventilators were found to be in desperately short supply, governors pleaded for them from the White House, which stalled, then called on private enterprise, which couldn’t deliver. States and cities were forced into bidding wars that left them prey to price gouging and corporate profiteering. Civilians took out their sewing machines to try to keep ill-equipped hospital workers healthy and their patients alive. Russia, Taiwan, and the United Nations sent humanitarian aid to the world’s richest power—a beggar nation in utter chaos.

If you read nothing else today, read this.

Quarantine diary — Day 31

This blog is now also available as a once-a-day email. If you think this might work better for you why not subscribe here? (It’s free and there’s a 1-click unsubscribe if you subsequently decide you need to prune your inbox!) One email a day, in your inbox at 07:00 every morning.