Facebook runs into a German wall

From the FT — probably paywalled.

Facebook suffered a setback in Germany on Tuesday after the country’s highest civil court ruled that it must comply with an order from the German antitrust watchdog and fundamentally change the way it handles users’ data.

The ruling by the federal court of justice in Karlsruhe takes aim at the way Facebook merges data from the group’s own services, such as WhatsApp and Instagram, with other data collected on third-party internet sites via its business tools.

In 2019, Germany’s cartel office blocked Facebook from pooling such data without user consent. Facebook later won a suspension of that decision from a court in Düsseldorf and wanted the pause to continue until a ruling on its appeal.

But on Tuesday the Karlsruhe court set aside the Düsseldorf ruling and backed the antitrust authorities, saying Facebook in future had to offer its users a choice when it collects and merges data from websites outside of its own ecosystem.

Interesting. Andreas Mundt, head of the German cartel office, is a determined and imaginative official. In a statement, he welcomed the decision. He said data was a decisive factor for economic power and for judging market power on the internet. “Today’s ruling gives us important clues as to how we should deal with the issues of data and competition,” he said, in comments quoted by DPA agency.

Progress, at last.

Mark Zuckerberg Believes Only in Mark Zuckerberg

Why is he abetting Trump while civil rights leaders and his own employees rebuke him? It’s about dominance.

At last, people are beginning to suss what it is about Zuckerberg that’s so weird. I’ve thought for years — on the basis of reading his public posts and watching his occasional (rare) public appearances — that he is fundamentally an autocratic sociopath. But because he’s so rich, the usual aphrodisiac effect of great wealth kicks in and journalists (and others) who should know better succumb to the idea that if he is so rich then he must be so smart. Well, he is smart. But he ain’t interested in other people, or capable of emphathising with them..

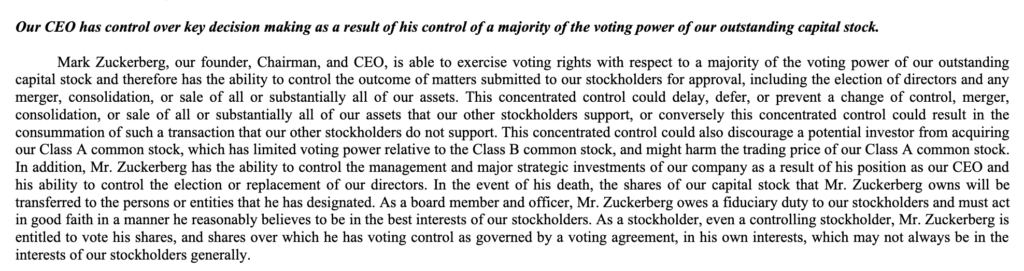

The autocratic bit is easy to document btw. You only have to look at the relevant paragraph in Facebook’s SEC filings.

Here it is (on page 25 of the filing

Siva Viadhyanathan has also been thinking about Zuckerberg for a long time and has now written an interesting essay on what he has finally concluded. He used to think of Zuckerberg, he says, as an idealist brought up in a bubble and so was puzzled by some of the things he allowed to happen (because, remember, he has absolute power over that company of his.) A key factor in Siva’s change of mind seems to have been Steven Levy’s book, Facebook: The Inside Story.

I expected that Zuckerberg was experiencing cognitive dissonance while watching his dear company be exploited to empower genocidal forces in Myanmar, religious terrorists in Sri Lanka, or vaccine deniers around the world.

I was wrong. I misjudged Zuckerberg. Another thing I learned from Levy’s book is that along with an idealistic and naive account of human communication, Zuckerberg seems to love power more than he loves money or the potential to do good in the world.

Having studied just enough Latin in prep school to get him in trouble, Zuckerberg was known to quote Cato, shouting “Carthago delenda est” (Carthage must be destroyed) when referring to Google. Emperor Augustus was a particular inspiration, Levy reports, and Zuckerberg named his child after Augustus, the adopted son of the tyrant Julius Caesar who ruled over the greatest and most peaceful span of the Roman Empire as its first emperor.

It was not Zuckerberg suffering from cognitive dissonance. I was. As I watched him cooly face questions from congressional representatives about the Cambridge Analytica debacle, he never seemed thoughtful, just disciplined.

That Facebook could serve people well—and it does—and that it could be abused to contribute to massive harm, pain, and death, didn’t seem to generate that one troublesome phenomenon that challenges the thoughtful: Contradiction.

Zuckerberg continued and continues to believe in the positive power of Facebook, but that’s because he believes in the raw power of Facebook. “Domination!,” he used to yell at staff meetings, indicating that everything is a game. Games can be won. He must win. If a few million bones get broken along the way, his game plan would still serve the greatest good for the greatest number.

He believes in himself so completely, his vision of how the world works so completely, that he is immune to cognitive dissonance. He is immune to new evidence or argument. It turns out megalomaniacs don’t suffer from cognitive dissonance.

Like the notorious architect Philip Johnson, or Robert Moses, the tyrannical planner of New York, Zuckerberg, says Siva,

is a social engineer. He knows what’s best for us. And he believes that what’s best for Facebook is best for us. In the long run, he believes, Facebook’s domination will redeem him by making our lives better. We just have to surrender and let it all work out. Zuckerberg can entertain local magistrates like Trump because Zuckerberg remains emperor.

Nice, perceptive essay by a formidable scholar.

Are Universities Going the Way of CDs and Cable TV?

Although it probably seems inconceivable to those of us who work in universities, the shock of the pandemic will lead to radical changes in the way most of these institutions work. This essay is interesting because it’s by Michael Smith, who is Professor of Information Technology and Marketing at Carnegie Mellon and the co-author of Streaming, Sharing, Stealing: Big Data and the Future of Entertainment.

He starts with a question the Wall Street Journal asked in April:

Do students think their pricey degrees are worth the cost when delivered remotely? “One student responded with this zinger, Smith writes,

“Would you pay $75,000 for front-row seats to a Beyoncé concert and be satisfied with a livestream instead?” Another compared higher education to premium cable—an annoyingly expensive bundle with more options than most people need. “Give me the basic package,” he said.

“As a parent of a college-age child”, Smith continues, “I’m sympathetic to these concerns. But as a college professor, I find them terrifying. And invigorating”.

Why terrifying?

Because I study how new technologies cause power shifts in industries, and I fear that the changes in store for higher education are going to look a lot like the painful changes we’ve seen in retail, travel, news, and entertainment.

Consider the entertainment industry.

Throughout the 20th century, the industry remained remarkably stable, despite technological innovations that regularly altered the ways movies, television, music, and books were created, distributed, and consumed. That stability, however, bred overconfidence, overpricing, and an overreliance on business models tailored to a physical world.

Trouble arrived early in the 21st century, when upstart companies powered by new digital technologies began to challenge the status quo. Entertainment executives reflexively dismissed the threat. Netflix was “a channel, not an alternative.” Amazon Studios was “in way over their heads.” YouTube? No self-respecting artist would ever use a DIY platform to start a career. In 1997, after one music executive heard songs compressed into the MP3 format, he refused to believe anybody would give up the sound quality of CDs for the portability of MP3s. “No one is going to listen to that shit,” he insisted. In 2013, the COO of Fox expressed similar skepticism about the impact of technological change on his business. “People will give up food and a roof over their head,” he told investors, “before they give up TV.”

We all know how that worked out: From 1999 to 2009, the music industry lost 50 percent of its sales. From 2014 to 2019, roughly 16 million American households canceled their cable subscriptions.

I remember this in the broadcasting business. In the mid- to late-1990s I was a consultant to a firm in the radio business. I spent many fruitless hours trying to explain to them the significance of streaming media, but they couldn’t get it. Where would all those servers come from? And what about the absence of broadband connections? And so on. The iPlayer and Video on Demand — and podcasting — were unimaginable then, even though they were emerging in embryonic form. (Anyone remember RealAudio?)

Similar dynamics are at play in higher education today, says Smith. Universities have long been remarkably stable institutions. But,

That stability has again bred overconfidence, overpricing, and an overreliance on business models tailored to a physical world. Like those entertainment executives, many of us in higher education dismiss the threats that digital technologies pose to the way we work. We diminish online-learning and credentialing platforms such as Khan Academy, Kaggle, and edX as poor substitutes for the “real thing.” We can’t imagine that “our” students would ever want to take a DIY approach to their education instead of paying us for the privilege of learning in our hallowed halls. We can’t imagine “our” employers hiring someone who doesn’t have one of our respected degrees.

But we’re going to have to start thinking differently…

Good essay. Worth reading in full if you work in Higher Ed. And the funniest thing of all is that Eli Noam published his amazingly far-sighted essay, “Electronics and the Dim Future of the University” in 1995! But it seems that no Vice-Chancellors or university Presidents read it! I did, though, because I was then teaching at the Open University, and of course we got it — but I guess that was probably because the OU was emphatically NOT a traditional university. We had no stake in the old system.

Oh, and if you haven’t been keeping up with how MOOCs have evolved, here’s a good example from Princeton.

Quarantine diary — Day 95

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!