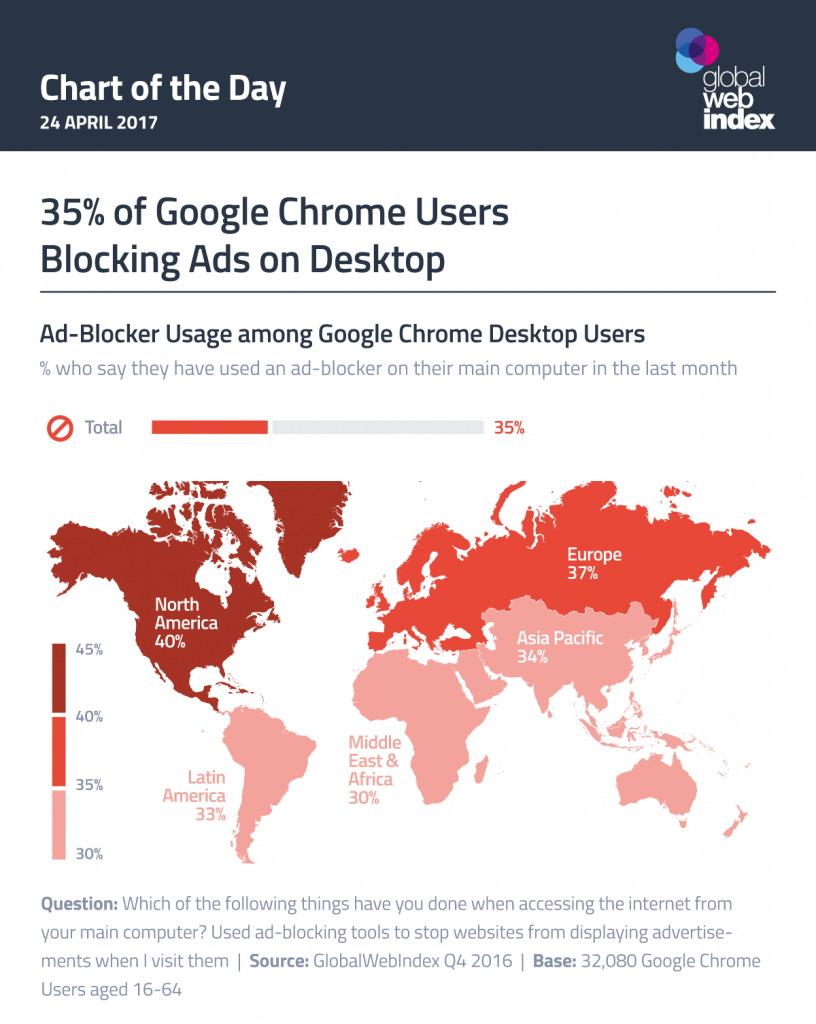

Google’s Chrome browser is popular world wide. And it turns out that many of its users don’t like ads — which is very naughty of them in an ad-based universe. But now there are rumours that Google plans to incorporate some kind of blocking of “unacceptable” ads in its browser. Which of course might be welcome to many users. But it would also make Google the arbiter of what is “unacceptable”.

Category Archives: Google

Digital realities

From an interesting NYT piece on how Google is coining money by allowing firms to put product information in the space immediately below the search bar.

Product ads that appeal to shoppers are also strategically important because consumers are starting their online shopping at Amazon.com. Last year, a survey of 2,000 American shoppers found that 55 percent turn to Amazon first when searching for a product, while only 28 percent start with a web search.

AI now plays pretty good poker. Whatever next?

This morning’s Observer column:

Ten years ago, [Sergey] Brin was running Google’s X lab, the place where they work on projects that have, at best, a 100-1 chance of success. One little project there was called Google Brain, which focused on AI. “To be perfectly honest,” Brin said, “I didn’t pay any attention to it at all.” Brain was headed by a computer scientist named Jeff Dean who, Brin recalled, “would periodically come up to me and say, ‘Look – the computer made a picture of a cat!’ and I would say, ‘OK, that’s very nice, Jeff – go do your thing, whatever.’ Fast-forward a few years and now Brain probably touches every single one of our main projects – ranging from search to photos to ads… everything we do. This revolution in deep nets has been very profound and definitely surprised me – even though I was right in there. I could, you know, throw paper clips at Jeff.”

Fast-forward a week from that interview and cut to Pittsburgh, where four leading professional poker players are pitting their wits against an AI program created by two Carnegie Mellon university researchers. They’re playing a particular kind of high-stakes poker called heads-up no-limit Texas hold’em. The program is called Libratus, which is Latin for “balanced”. There is, however, nothing balanced about its performance…

Google’s insatiable appetite

‘Transparency’: like motherhood and apple pie

This morning’s Observer column:

On 25 October, the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, wandered into unfamiliar territory – at least for a major politician. Addressing a media conference in Munich, she called on major internet companies to divulge the secrets of their algorithms on the grounds that their lack of transparency endangered public discourse. Her prime target appeared to be search engines such as Google and Bing, whose algorithms determine what you see when you type a search query into them. Given that, an internet user should have a right to know the logic behind the results presented to him or her.

“I’m of the opinion,” declared the chancellor, “that algorithms must be made more transparent, so that one can inform oneself as an interested citizen about questions like, ‘What influences my behaviour on the internet and that of others?’ Algorithms, when they are not transparent, can lead to a distortion of our perception; they can shrink our expanse of information.”

All of which is unarguably true…

Digital Dominance: forget the ‘digital’ bit

Some reflections on the symposium on “Digital Dominance: Implications and Risks” held by the LSE Media Policy Project on July 8, 2016.

In thinking about the dominance of the digital giants1 we are ‘skating to where the puck has been’ rather than to where it is headed. It’s understandable that scholars who are primarily interested in questions like media power, censorship and freedom of expression should focus on the impact that these companies are having on the public sphere (and therefore on democracy). And these questions are undoubtedly important. But this focus, in a way, reflects a kind of parochialism that the companies themselves do not share. For they are not really interested in our information ecosystem per se, nor in democracy either, if it comes to that. They have bigger fish to fry.

How come? Well, there are two reasons. The first is that although those of us who work in media and education may not like to admit it, our ‘industries’ are actually pretty small beer in industrial terms. They pale into insignificance compared with, say, healthcare, energy or transportation. Secondly, surveillance capitalism, the business model of the two ‘pure’ digital companies — Google and Facebook — is probably built on an unsustainable foundation, namely the mining, processing, analysis and sale of humanity’s digital exhaust. Their continued growth depends on a constant increase in the supply of this incredibly valuable (and free) feedstock. But if people, for one reason or another, were to decide that they would prefer to be doing something other than incessantly checking their phones, Googling or updating their social media statuses, then the evaporation of those companies’ stock market valuations would be a sight to behold. And while one can argue that such an outcome seems implausible, because of network effects and other factors, then a glance at the history of the IT industry might give you pause for thought.

The folks who run these companies understand this. For if there is one thing that characterizes the leaders of Google and Facebook it is their determination to take the long, strategic view. This is partly a matter of temperament, but it is powerfully boosted by the way their companies are structured: the founders hold the ‘golden shares’ which ensures their continued control, regardless of the opinions of Wall Street analysts or ordinary shareholders. So if you own Google or Facebook stock and you don’t like what Larry Page or Mark Zuckerberg are up to, then your only option is to dispose of your shares.

Being strategic thinkers, these corporate bosses are positioning their organizations to make the leap from the relatively small ICT industry into the much bigger worlds of healthcare, energy and transportation. That’s why Google, for example, has significant investments in each of these sectors. Underpinning these commitments is an understanding that their unique mastery of cloud computing, big data analytics, sensor technology, machine learning and artificial intelligence will enable them to disrupt established industries and ways of working in these sectors and thereby greatly widen their industrial bases. So in that sense mastery of the ‘digital’ is just a means to much bigger ends. This is where the puck is headed.

So, in a way, Martin Moore’s comparison2 of the digital giants of today with the great industrial trusts of the early 20th century is apt. But it underestimates the extent of the challenges we are about to face, for our contemporary versions of these behemoths are likely to become significantly more powerful, and therefore even more worrying for democracy.

So what was Google smoking when it bought Boston Dynamics?

This morning’s Observer column:

The question on everyone’s mind as Google hoovered up robotics companies was: what the hell was a search company doing getting involved in this business? Now we know: it didn’t have a clue.

Last week, Bloomberg revealed that Google was putting Boston Dynamics up for sale. The official reason for unloading it is that senior executives in Alphabet, Google’s holding company, had concluded (correctly) that Boston Dynamics was years away from producing a marketable product and so was deemed disposable. Two possible buyers have been named so far – Toyota and Amazon. Both make sense for the obvious reason that they are already heavy users of robots and it’s clear that Amazon in particular would dearly love to get rid of humans in its warehouses at the earliest possible opportunity…

Privacy is sooo… yesterday: Google’s Chief Economist

“One easy way to forecast the future is to predict that what rich people have now, middle class people will have in five years, and poor people will have in ten years. It worked for radio, TV, dishwashers, mobile phones, flat screen TV, and many other pieces of technology.

What do rich people have now? Chauffeurs? In a few more years, we’ll all have access to

driverless cars. Maids? We will soon be able to get housecleaning robots. Personal assistants? That’s Google Now. This area will be an intensely competitive environment: Apple already has Siri and Microsoft is hard at work at developing their own digital assistant. And don’t forget IBM’s Watson.Of course there will be challenges. But these digital assistants will be so useful that everyone will want one, and the scare stories you read today about privacy concerns will just seem quaint and oldfashioned.”

Hal Varian, “Beyond Big Data”, NABE Annual Meeting, September 10, 2013, San Francisco.

Facebook can’t be just a ‘platform’ if it’s distributing news

This morning’s Observer column:

Many years ago, the political theorist Steven Lukes published a seminal book – Power: A Radical View. In it, he argued that power essentially comes in three varieties: the ability to compel people to do what they don’t want to do; the capability to stop them doing what they want to do; and the power to shape the way they think. This last is the kind of power exercised by our mass media. They can shape the public (and therefore the political) agenda by choosing the news that people read, hear or watch; and they can shape the ways in which that news is presented. Lukes’s “third dimension” of power is what’s wielded in this country by outlets like Radio 4’s Today programme, the Sun and the Daily Mail. And this power is real: it’s why all British governments in recent years have been so frightened of the Mail.

But as our media ecosystem has changed under the impact of the internet, new power brokers have appeared….

Big data: the new gasoline

This morning’s Observer column:

“Data is the new oil,” declared Clive Humby, a mathematician who was the genius behind the Tesco Clubcard. This insight was later elaborated by Michael Palmer of the Association of National Advertisers. “Data is just like crude [oil],” said Palmer. “It’s valuable, but if unrefined it cannot really be used. It has to be changed into gas, plastic, chemicals, etc to create a valuable entity that drives profitable activity; so must data be broken down, analysed for it to have value.”

There was just one thing wrong with the metaphor. Oil is a natural resource; it has to be found, drilled for and pumped from the bowels of the Earth. Data, in contrast, is a highly unnatural resource. It has to be created before it can be extracted and refined. Which raises the question of who, exactly, creates this magical resource? Answer: you and me…