This morning’s Observer column:

In a modest way, Kosinski, Stillwell and Graepel are the contemporary equivalents of [Leo] Szilard and the theoretical physicists of the 1930s who were trying to understand subatomic behaviour. But whereas the physicists’ ideas revealed a way to blow up the planet, the Cambridge researchers had inadvertently discovered a way to blow up democracy.

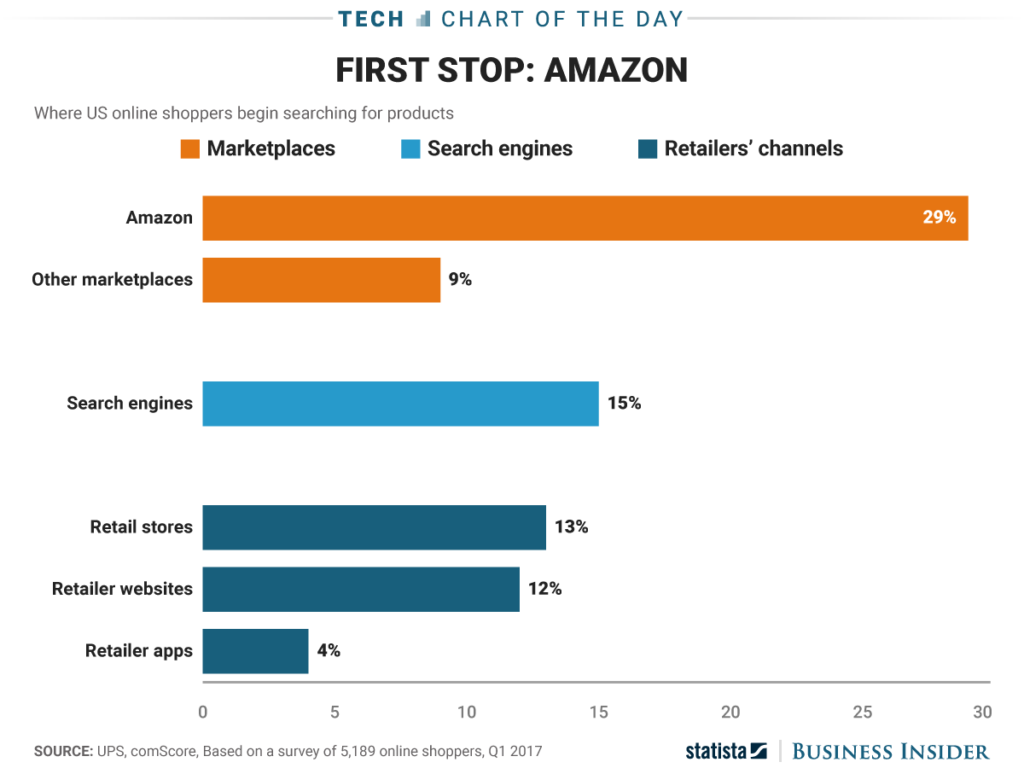

Which makes one wonder about the programmers – or software engineers, to give them their posh title – who write the manipulative algorithms that determine what Facebook users see in their news feeds, or the “autocomplete” suggestions that Google searchers see as they begin to type, not to mention the extremist videos that are “recommended” after you’ve watched something on YouTube. At least the engineers who built the first atomic bombs were racing against the terrible possibility that Hitler would get there before them. But for what are the software wizards at Facebook or Google working 70-hour weeks? Do they genuinely believe they are making the world a better place? And does the hypocrisy of the business model of their employers bother them at all?

These thoughts were sparked by reading a remarkable essay by Yonatan Zunger in the Boston Globe, arguing that the Cambridge Analytica scandal suggests that computer science now faces an ethical reckoning analogous to those that other academic fields have had to confront…