This blog is now also available as a once-a-day email. If you think this might work better for you why not subscribe here? (It’s free and there’s a 1-click unsubscribe if you subsequently decide you need to prune your inbox!) One email a day, in your inbox at 07:00 every morning.

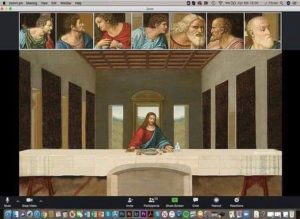

One of the Zoom memes circulating on social media.

How is the Cloud standing up to the Coronavirus stress-test?

Reasonably well — at least according to this report. Headlines: Microsoft’s Azure has had some minor problems. On the assumption that no news is good news, Amazon’s AWS seems fine. Which is just as well, because an astonishing proportion of the services we are relying on now runs partly or exclusively on AWS. We tend to think of Amazon as a retail or e-commerce monopoly. But actually its cloud computing service is probably more important: it’s become critical infrastructure for the world. A point to be borne in mind when we eventually get round to thinking about regulation.

Boredom? Nah

For most people, the novelty of self-isolation has worn off, and many will doubtless be thinking about how long we — as people, and as a society — can sustain this. For some, isolation is really hard to bear, and there’s a real cost — in terms of loneliness, domestic violence, marital breakdown, depression. mental illness and boredom, to name just a few of the downsides — to be paid for this strategy to slow the spread of the virus. As far as the last of those downsides, however, some people (including me) are temperamentally lucky in that they’ve never been bored. My friend Quentin Stafford-Fraser is the same, and he has a lovely blog post today about “Boredom, Toothbrushes and Terminals”.

One day, the UK might have a proper Opposition party again. In which case it needs to start thinking about the future rather than the past

Keir Starmer QC has been elected Leader of the Labour party by a landslide. So maybe the country will eventually have an Opposition that’s functioning as an opposition should in this two-party system. It will also need to start thinking about life after Corona. And when it does it will have to do better than Dominic Cumming’s half-assed idea of rebooting Britain by having an ARPA 2.0 modelled on the famous Pentagon agency which funded the Internet and a host of other interesting stuff in the US. (ARPA is one of Cummings’s obsessions. Another one is the Manhattan Project which built the first atomic bomb.)

Don’t get me wrong I’ve got nothing against ARPA. (In fact it figures significantly in my book on the origins of the Internet. And I was lucky enough to know Bob Taylor, the guy who funded the ARPANET, the precursor of the Internet we use today.) It’s an interesting idea to see if the post-Brexit UK could get a creative and technological boost from trying to replicate the idea here. (For an extended discussion of the idea, see this think-tank report). The problem is that even if it had the kinds of upsides that Cummings desires, it would do little to address the country’s most pressing need — which is, to use a Johnsonian phrase, “levelling up” — i.e. addressing the challenge of reinvigorating the vast swathes of the country which have been “left behind” by neoliberal economic policy, globalisation and economic change. The truth is that a successful ARPA 2.0 would merely create another mini-Silicon Valley in Britain (to complement the Cambridge cluster and the Shoreditch crowd). It might generate great wealth for small elites, but it would not provide much in the way of employment (except as low-skilled service workers) for those who have lost out over the last two decades. Just see how much of the fabulous wealth of Google et al has trickled down to the ordinary folks of San Jose, Mountain View, Cupertino or San Francisco.

So if this or the next UK government (which could conceivably be led by Starmer, if the Coronacrisis turns out to be catastrophic) is serious about levelling up, then what Britain needs is a concerted, government-led effort on the Manhattan project scale. This initiative, however, will not be about handing out welfare to distressed areas but about decarbonising the UK, and it will create work for an awful lot of people who don’t know anything about data analytics. It will involve retrofitting every house in the country to make it as energy-efficient as possible, replacing oil and gas boilers with air-and ground-source heating systems, fitting solar panels everywhere, reforming the construction industry so that every new building is energy-efficient, and a thousand other things — plus creating the education and training infrastructure to enable this to happen. It’s about rebooting the whole country, providing the self-esteem in depressed areas that comes from being able to earn a good living doing work that is patently useful, and acquiring relevant new skills and knowledge in the process. As Alan Kay used to say, the best way to predict the future is to invent it. And that doesn’t just apply to computers.

The Briefing Room

Terrific Radio 4 programme this morning on the Coronavirus.

It tackled three specific questions: 1. What testing does 2. The search for a vaccine 3. Whether any existing drug might be useful in suppressing COVID-19 and lightening the health service burden

No nonsense. Interviewed real experts. Was illuminating, interesting and very well-informed.

A model of what public service broadcasting is for.