Breakfasting in style

The view from my window one morning in a posh German schloss outside Frankfurt where I was doing a gig.

Quote of the Day

”I saw his play under bad conditions. The curtain was up.”

George Kaufman, playwright and critic, writing of Alexander Woollcott.

Musical replacement for the morning’s radio news

Sleepwalk – Chet Atkins & Leo Kottke

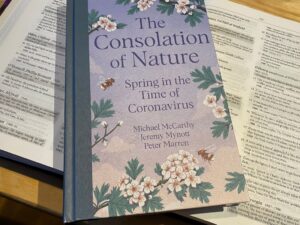

The Consolation of Nature

This is the title of a delightful new book that arrived in the post yesterday (the day of its publication in the UK). It’s a joint work by three friends who are distinguished writers on natural history and the environment — Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren. They live in different parts of the country and decided to record and exchange their reflections on the most extraordinary Spring that any of us have ever experienced. The result is an entrancing book, IMHO.

Here’s a fragment of the Introduction, read by me…

As someone who has also written a lockdown diary (coming soon) I’m deeply impressed by how insightful (and observant) the members of this trio have been as they lived through the same experience.

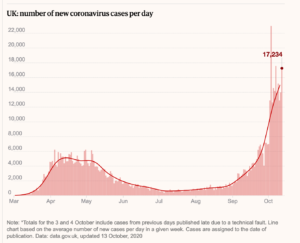

We’re in a syndemic, not a pandemic

I’ve been watching the latest UK government ‘briefing’ on the pandemic and brooding on how most Western states’ responses to Covid remain as predictable as they are inadequate. It’s eerie to watch whole societies unable to grasp the systemic nature of what’s happening.

Essentially the response is reductionist — tackle the virus, tackle the virus, tackle the virus. (Oh, and protect the economy.) But in fact we’re in a perfect storm in which the virus is just one actor. The legacies of 40 years of ideologically-driven government have generated huge inequalities which have exacerbated poverty, grotesque housing shortages and fostered massive increases in chronic diseases — obesity, diabetes, depression, anxiety, heart disease — all of which create the susceptibilities to the virus that are now becoming apparent.

We need a systems approach to this, because it’s a systemic problem that just happens to have become truly catastrophic because of the virus. What we have — as The Lancet has been arguing — is a ‘syndemic’, not a pandemic. The hallmark of a syndemic, it says,

is the presence of two or more disease states that adversely interact with each other, negatively affecting the mutual course of each disease trajectory, enhancing vulnerability, and which are made more deleterious by experienced inequities.

Focussing on the virus alone is understandable (i.e. obsessing only about treatments and vaccines) is a mistake . The FT had a quote from Richard Horton, Editor of The Lancet, making the point:

”The deadly impact of the pandemic is not caused by the virus acting alone but interacting with chronic disease like diabetes, obesity, heart disease and high blood pressure — all against a background of inequality of poverty. We can’t fully control the infection without addressing those factors”.

The trouble is that we no longer have a politics that can do systemic thinking. As an academic I’m beginning to think that we need a ‘theory of incompetent systems’, i.e. systems that can’t fix themselves. Climate change provides another demonstration of that need. And the US Constitution is yet another.

A student reference in the age of Zoom

Matt Cheung in McSweeney’s…

I am writing regarding Sara Tan’s application for the Covid Undergraduate Research Scholars Educational Development scholarship, which seeks to reward students exhibiting extraordinary academic skills, creativity, and leadership abilities during this time of uncertainty. I met Sara this fall semester as she was enrolled in my first-year composition class. In the time I have known her, she has proven to be a hard-working student worthy of your consideration.

You may wonder how I have come to know Sara so well when our college has been virtually shut down save for essential staff, such as our finance department, the volunteers that feed the feral cats on campus, and the occasional faculty member who wanders onto the grounds looking for a sense of a connection to the past he once had in order to fight feeling completely untethered during this pandemic. I’m not saying that person is me, but I digress. This is about Sara. Sara has been very active in our Zoom classes. She never turns her camera on, but it is always a delight to see her black box log in with its three dancing dots struggling to establish audio and find a connection, any connection – physical, spiritual, emotional – in the dark void that is the new college classroom. I’ve come to expect Sara’s disembodied voice, floating through my speakers, to offer pithy observations about the day’s text. Her contributions in the chat are equally insightful, always complete sentences or at least a clause with a subject and a verb, far more than her classmates’ single-word utterings.

It’s hard to establish relationships with students you only see virtually, but I have gotten to know Sara’s personality and creative side through her use of GIFs…

Wonderful. Wish I could write references like that!

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!