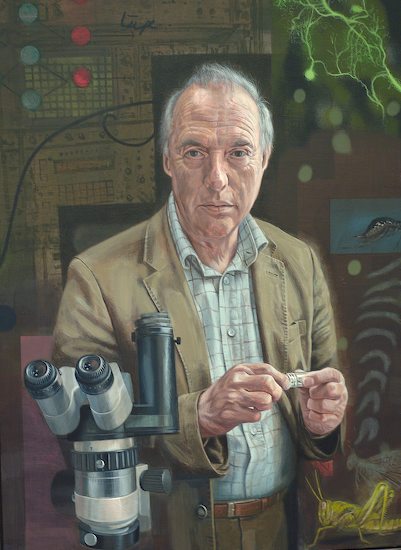

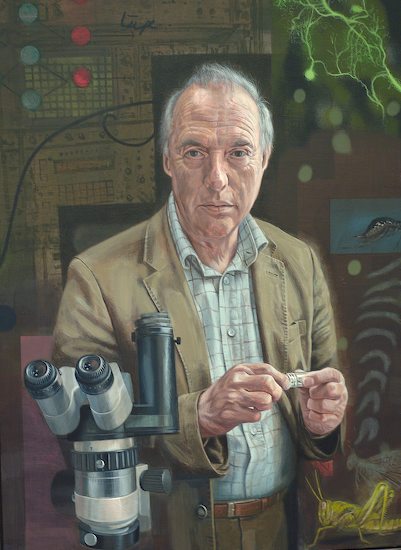

My friend and Wolfson colleague Malcolm Burrows is retiring from his position as Head of the Department of Zoology in Cambridge, and his colleagues put on a whole day of talks to mark the occasion. Even the Vice Chancellor showed up — to explain how, shortly after her arrival in Cambridge, Malcolm had managed to persuade her to do something she hadn’t wanted to do “without ever raising his voice”. (The visit that resulted from that conversation, incidentally, led to an endowed Chair in his Department.) At the end of her speech, she unveiled the portrait by Tom Wood (who did the National Portrait Gallery’s portrait of David Hockney) which has been commissioned to honour him.

Malcolm is one of the cleverest, nicest and sanest people I know. Unlike many high-profile academics, he doesn’t do histrionics. Yet during his tenure, the Cambridge department became the best Zoology department in the country, and one of the best in the world. Unusually for such a large, high-octane outfit it also seems remarkably friendly. Certainly there was a lovely, affectionate tone to the day’s proceedings.

Malcolm’s speciality is neurophysiology — more specifically the neuronal mechanisms by which a nervous system generates and controls natural movements (top right in the portrait). His chosen animals are insects, including some (locusts) that you wouldn’t want to meet on a dark night (bottom right in the portrait). One of his colleagues captured his character neatly when he said that he combined a childlike delight in insects with a very grown-up style of administration. During his tenure, for example, the University’s central authority (the General Board) agreed to write off a huge ancient debt which had for decades “squatted like a huge black toad” on the Department’s back. And, believe me, the General Board didn’t get where it is today by writing off departmental ‘debts’.

It was a really nice occasion which reminded one firstly, of how important people are, even in prestigious institutions, and secondly, what a difference good leadership makes. Most of all, it was reassuring to know that, tomorrow, Malcolm will be back in his lab. He may be technically ‘retired’, but most people wouldn’t guess that.

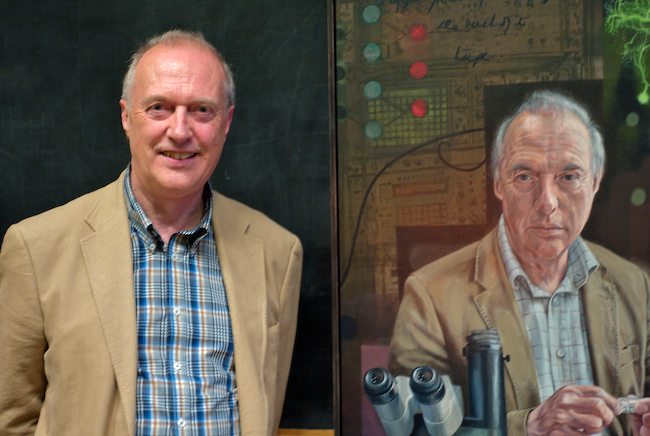

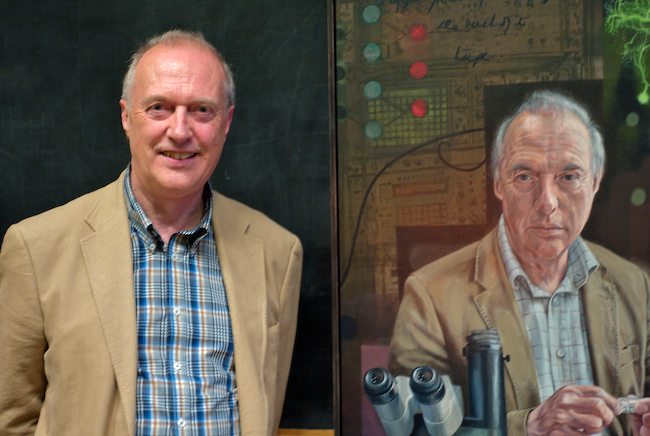

Before I left, I asked him to pose with his portrait. Here’s the result.