Quote of the Day

Novelist Roddy Doyle on being famous in Ireland:

“I was waiting at Tara Street Dart station for a friend, and there was a bunch of lads coming down the quays, all in their late teens, lads in tracksuits, and one of them broke away and came right up to my face and said, ‘Are you Roddy Doyle?’”

“And I said, ‘I am, yeah.’”

“He said, ‘So what?’”

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

J.S. Bach | Violin Concerto No.1 in A minor, BWV 1041 | 2. Andante

Link

Long Read of the Day

The End of Books by Justin E. H. Smith

Lovely essay on the difficulties faced by all those who (like this blogger) have a ’book problem’ (to use a euphemism for a chronic addiction).

Moving to Paris in 2013, I found a temporary solution to the problem of my personal library. I drove the vastly greater part of the books I had accumulated over the years to a very generous relative’s home in Upstate New York, somewhere between the Hudson River and the Finger Lakes, and stored them in her spacious attic.

Over the years many people have told me there are inexpensive ways to ship books across the ocean, that enterprising Poles have established their own trans-Atlantic routes serving the Polish diaspora but also accommodating American expatriates, or that the US Postal Service itself offers special book rates “by the crate”. When called upon kindly to show me how these services may be accessed, somehow the people so ready to offer this advice never follow through. So just trust me: however you pack them up, whichever service you use, Concorde or barge, it would cost a fortune to get all of my books across the Atlantic.

And so for years I let them bake up there, and then freeze, and then bake again, a significant portion of the greatest thoughts ever expressed by human beings, huddling together, not exactly thinking on their own, but perhaps waiting, with dim awareness of their true “end”, to incite thought again.

Do read the whole thing.

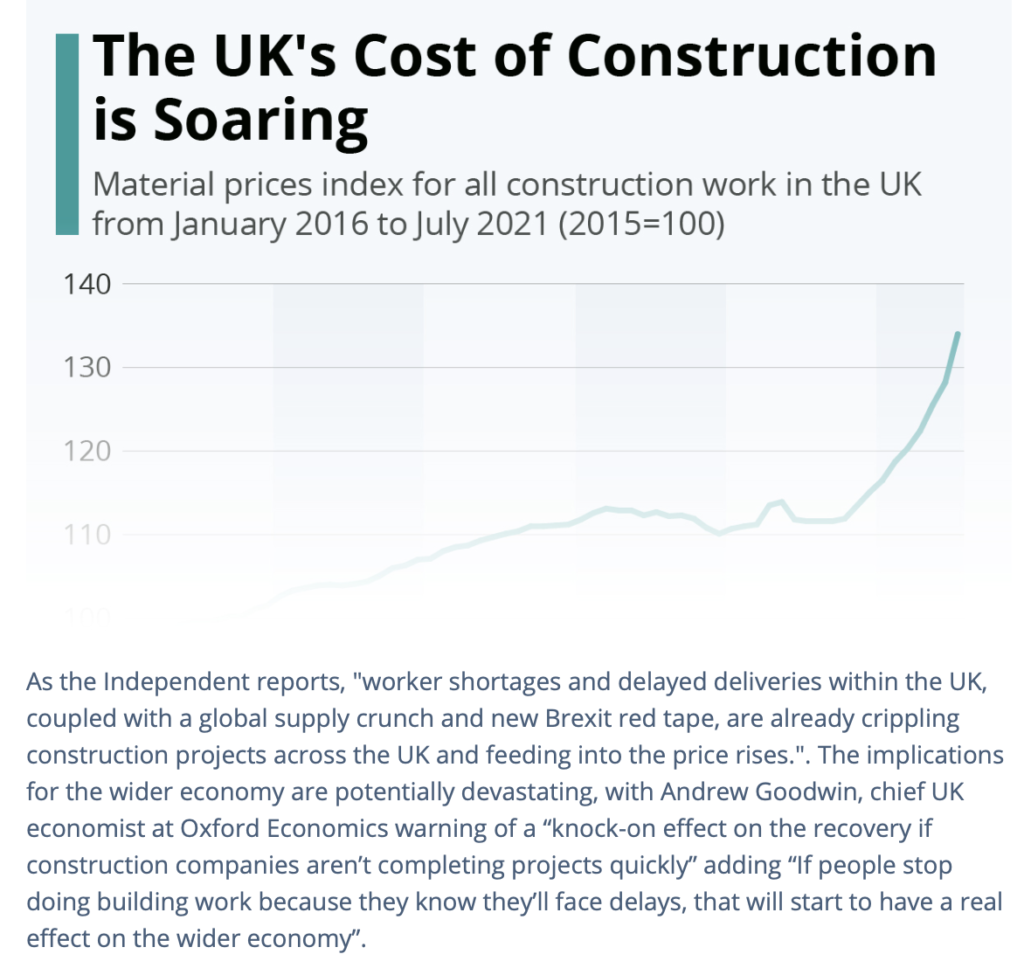

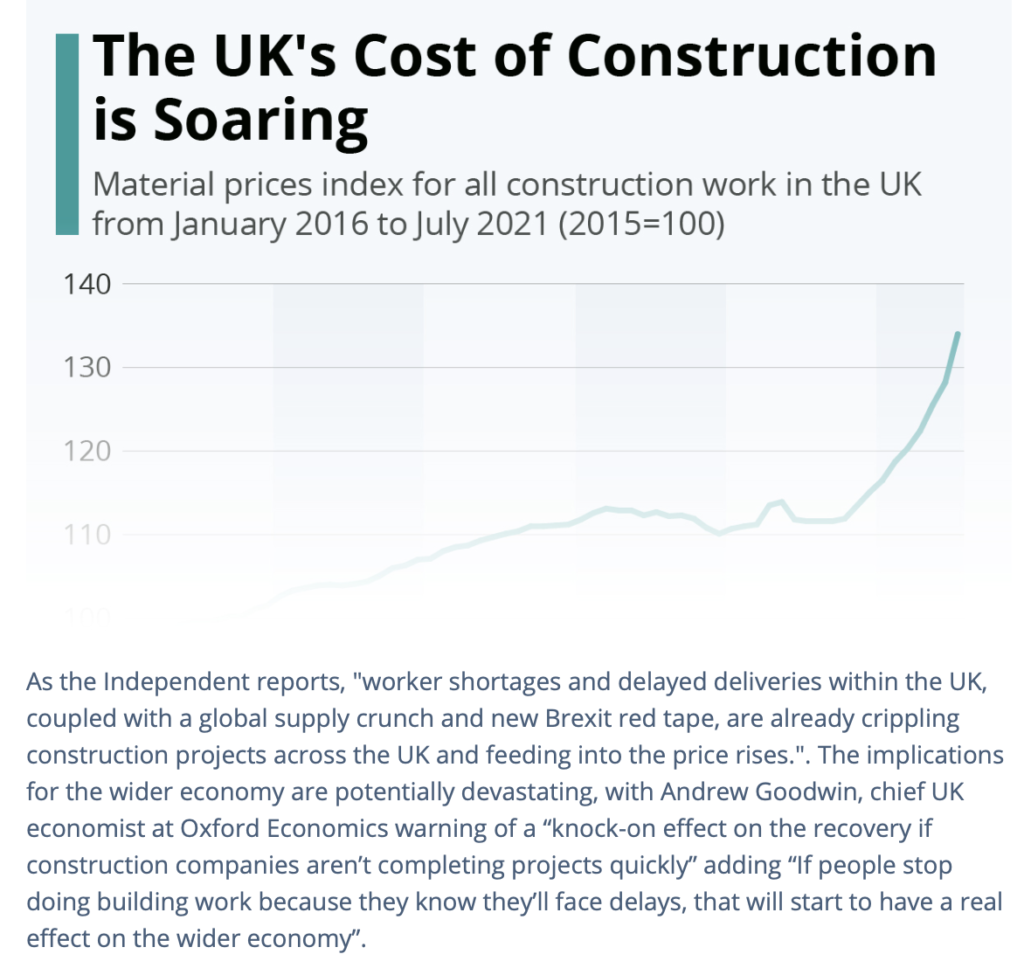

Chart of the day

The usefulness of sharp criticism

Joan Bakewell (Whom God Preserve) tells a nice story about her days as a student reading history in Cambridge. She had written an exuberant essay on the French Revolution and submitted it to her tutor, Betty Behrens:

I saw it as a new dawn of freedom and fulfilment such as Cambridge meant to me: humankind united, happiness for all, triumph over tyranny.

The essay came back untouched. I thought there must be some mistake. I had delivered it as required, on time, impeccably handwritten. Now it lay on my table exactly as I had written it: no annotations, no corrections of dates or names, nothing. My newfound exhilaration wilted. What of my rhetoric, my exhortations, my vision of humankind – had they been somehow overlooked?

The truth was worse. On the final page, there was indeed an intervention by Betty Behrens: a line drawn through my writing and a terse paragraph.

This piece of work was not worthy of any consideration by her: she refused to consider it. It was worthless, trite rubbish. If I was to continue to study with her, there must be a serious effort to understand what scholarship was.

I was knocked back with the force of her disapproval.

But…

In the event, the shock of her rebuke paid off. I had nowhere to go but into my own head. The thought of sharing my shame with college colleagues was out of the question. I had some serious thinking to do. I went back to my books: the lucid prose of Keynes, the measured tones of Plumb, the steady logic of Butterfield … the standard texts of the day. If I found them stuffy, that was my problem. Rhetoric and polemic had no place in the serious matter of study. (If I wanted invective, I could and did attend the lectures of FR Leavis, the celebrated English don, and hear him inveigh against WH Auden: “Mmmister Auden …” he would sneer.)

It proved a turning point for me. It was a healthy attack against my vanity, but more importantly made me examine how I thought. I began to examine what shaped my ideas – indeed, what shaped anyone’s ideas. Where did the whole direction of western thought come from? Yes, I allowed myself some grandiosity. But I wanted and intended to do better.

This rang bells for me — and also for some of my readers. Many comments one receives on draft papers are polite and modestly useful. But in a way they merely buttress or reinforce your preconceptions. The really useful criticism is often the most severe, because then you know you have struck bedrock and need to do something about it.

The Shakespeare and Company Project

Sylvia Beach was a legendary English-language bookseller in early 20th century Paris who created a bookstore that served as a kind of home-from-home for impecunious literary ex-pats. Famously, she was also the publisher of James Joyce’s Ulysses. But something I hadn’t known is that she also ran a lending library for her customers.

Her papers are in Princeton University where the library now runs The Shakespeare and Company Project which uses the Beach Papers to recreate the world of a lost literary generation. It’s all online. You can browse and search the lending library’s members and books; learn about what was involved in joining it; discover its most popular books and authors; download Project data. And more.

Beach closed the store in 1941 after refusing to sell her last remaining copy of Ulysses to a Nazi officer. This puzzled me because I have a vivid memory of visiting what I thought was the store on my first visit to Paris in 1968.

Was this further confirmation of Mark Twain’s observation that “the older I get the more clearly I remember things that never happened”?

But then Wikipedia came to my aid.

A later independent English-language bookstore was opened in 1951 by George Whitman, also located on Paris’ Left Bank, but under a different name. Whitman adopted the “Shakespeare & Co.” name for his store in 1965, and it continues to operate under that name to this day.

Today, it continues to serve as a purveyor of new and second-hand books, as an antiquarian bookseller, and as a free reading library open to the public. Additionally, the shop houses aspiring writers and artists in exchange for their helping out around the bookstore. Since the shop opened in 1951, more than 30,000 people have slept in the beds found tucked between bookshelves. The shop’s motto, “Be Not Inhospitable to Strangers Lest They Be Angels in Disguise,” is written above the entrance to the reading library.

Many thanks to Faith Johnson, who told me about the Princeton project.

This blog is also available as a daily newsletter. If you think this might suit you better why not sign up? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-button unsubscribe if you conclude that your inbox is full enough already!