Spotted in a friend’s garden.

Spotted in a friend’s garden.

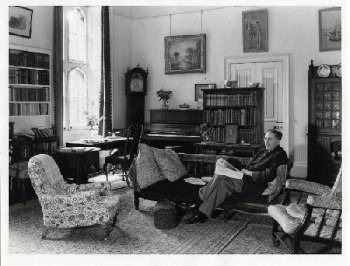

One of the highlights of my student career was meeting E.M. Forster. Carol (my first wife) and I were members of the Cambridge Humanists, and the society threw a party for Forster on his 90th birthday. It was held in King’s, where he was a Life Fellow (the photograph, taken in 1968, shows him in his Set) and hosted by Francis Crick who — as a Nobel laureate — was Cambridge’s most prominent humanist at the time (and may even have been the society’s Patron). Forster was in a chair (it may have been wheelchair — on that my memory is foggy) and sat quietly while a good deal of celebratory bedlam — which he viewed with a mildly quizzical expression — went on around him.

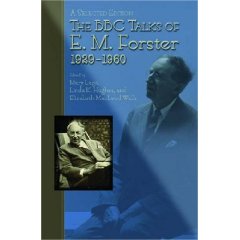

As someone whose pet hate is people who are endowed with certainty: religious fundamentalists, for example and ideological fanatics — I’ve always admired Forster for his uncertainty, open-mindedness and willingness to entertain the thought that he might be wrong. So the works of his that I’ve enjoyed most have been his essays, and the broadcast talks he gave on the BBC. Which is why it’s wonderful to discover that the collected talks have now been published in a handsome, footnoted edition.

Zadie Smith (whose novel On Beauty was allegedly inspired by Forster’s Howard’s End) has written a thoughtful review in the current issue of the New York Review of Books. “In the taxonomy of English writing”, she writes,

E.M. Forster is not an exotic creature. We file him under Notable English Novelist, common or garden variety. Still, there is a sense in which Forster was something of a rare bird. He was free of many vices commonly found in novelists of his generation—what’s unusual about Forster is what he didn’t do. He didn’t lean rightward with the years, or allow nostalgia to morph into misanthropy; he never knelt for the Pope or the Queen, nor did he flirt (ideologically speaking) with Hitler, Stalin, or Mao; he never believed the novel was dead or the hills alive, continued to read contemporary fiction after the age of fifty, harbored no special hatred for the generation below or above him, did not come to feel that England had gone to hell in a hand-basket, that its language was doomed, that lunatics were running the asylum, or foreigners swamping the cities.

Smith’s angle is that Forster was the ultimate middleman. He was, she thinks,

a tricky bugger. He made a faith of personal sincerity and a career of disingenuousness. He was an Edwardian among Modernists, and yet—in matters of pacifism, class, education, and race—a progressive among conservatives. Suburban and parochial, his vistas stretched far into the East. A passionate defender of “Love, the beloved republic,” he nevertheless persisted in keeping his own loves secret, long after the laws that had prohibited honesty were gone. Between the bold and the tame, the brave and the cowardly, the engaged and the complacent, Forster walked the middling line.

I’ve always thought of him as the epitomé of mild common sense. He understood the primacy of friendship, for example, and his aphorism about it (that if he had to choose between betraying his country and betraying his friend he hoped he’d have the courage to do the former) is a pretty good guide for living. And, when one remembers the jingoistic times in which he said that, it’s a aphorism that took courage to articulate.

In fact, he’s always seemed to me to be, in his mild-mannered way, rather courageous. He was a distinguished humanist, but one who recognised that the creed had its weaknesses: “the humanist shirks responsibility”, he wrote, “dislikes making decisions, and is sometimes a coward”. But during the war and the years running up to it Forster didn’t display much cowardice. He ridiculed Nazi “philosophy” from the early 1930s onward, attacked the prison and police systems, defended the Third Program, spoke up for mass education, the rights of refugees, free concerts for the poor, and art for the masses. In other words, he kept faith with liberal principles that many of his more cocksure contemporaries abandoned. “Do we, in these terrible times”, he asked, “want to be humanists or fanatics? I have no doubt as to my own wish, I would rather be a humanist with all his faults, than a fanatic with all his virtues.”

Right on.

Might be worth considering this from Good Morning Silicon Valley.

If you’re looking to get outraged by a government’s intrusion into the electronic lives of its citizens, you don’t need to look all the way to China. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security recently revealed its current border policy on laptops, iPods and other gadgets carried into the country by returning travelers or foreign visitors, and it boils down to this: Without explanation, we can seize your laptop or any device capable of storing information (including cell phones, thumb drives, video tapes, and old-fashioned analog paper). We can keep it as long as we want. We can look through the contents, and we can share them with other agencies or private entities. And we can do all this whenever and to whomever we want — no reasonable cause needed, not even a vague suspicion of wrongdoing. And, of course, this is all OK because we are protecting our treasured American freedom.

The House of Commons Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport has been pondering the ‘problem’ of ‘unsuitable’ online content and, having deliberated, has brought forth a report which is a flake of Cadbury proportions. Here’s an excerpt from the Summary:

Sites which host user-generated content—typically photos and videos uploaded by members of the public—have taken some steps to set minimum standards for that content. They could and should do more. We recommend that terms and conditions which guide consumers on the types of content which are acceptable on a site should be prominent. It should be made more difficult for users to avoid seeing and reading the conditions of use: it would then become more difficult for users to claim ignorance of terms and conditions if they upload inappropriate content.

It is not standard practice for staff employed by social networking sites or video-sharing sites to preview content before it can be viewed by consumers. Some firms do not even undertake routine review of material uploaded, claiming that the volumes involved make it impractical. We were not persuaded by this argument, and we recommend that proactive review of content should be standard practice for sites hosting user-generated content. We look to the proposed UK Council to give a high priority to reconciling the conflicting claims about the practicality and effectiveness of using staff and technological tools to screen and take down material. We also invite the Council to help develop agreed standards across the Internet industry on take-down times—to be widely publicised—in order to increase consumer confidence.

It is common for social networking sites and sites hosting user-generated content to provide facilities to report abuse or unwelcome behaviour; but few provide a direct reporting facility to law enforcement agencies. We believe that high profile facilities with simple, preferably one-click mechanisms for reporting directly to law enforcement and support organisations are an essential feature of a safe networking site. We would expect providers of all Internet services based upon user participation to move towards these standards without delay…

One wonders if any of the boobies who sit on the Committee have ever actually used the Internet. I’ve just checked with Flickr (one of the user-generated content sites which exercises these Tribunes of the People). A total of 4,219 images were uploaded to it in the last minute.

Charles Arthur has the measure of these crazies.

And then they drop the big idea: “We recommend that proactive review of content should be standard practice for sites hosting user-generated content.” Not just that, but there should be a hotline to the police: “Few [social sites] provide a direct reporting facility to law enforcement agencies. We believe that high profile facilities with simple, preferably one-click mechanisms for reporting directly to law enforcement and support organisations are an essential feature of a safe networking site.”

And as if that weren’t enough, their final, big, razzle-dazzle is a call for, yes, a centralised body, a fabulous new self-regulatory quango:

“Under which the industry would speedily establish a self-regulatory body to draw up agreed minimum standards based upon the recommendations of the UK council for child internet safety, monitor their effectiveness, publish performance statistics, and adjudicate on complaints. In time, the new body might also take on the task of setting rules governing practice in other areas such as online piracy and peer to peer file-sharing, and targeted or so-called “behavioural” advertising.”

Oh, my aching neurons. Let’s start at the top. Proactive review? That means checking before putting up. That means one pair of eyes per pair of eyes uploading stuff. Unfeasible, unless we demand Facebook employ, say, 50,000 new staff to look over all the content being uploaded by Facebook’s 8 million-plus UK users. Hey, I’m sure Mark Zuckerberg would be delighted.

A hotline to the police? Have you noticed how uninterested the police are when you call them to say that your bank card has been cloned and hundreds taken from your account? And how will they deal with a zillion people clicking “report to police” each time someone says, “I’m going to kill you!” on some user forum? The problem with this is that it doesn’t – to use the net phrase – “scale”.

Bill Thompson also has a go at this in Index on Censorship.

A bunch of MPs has decided the best way to get some publicity at the start of the summer recess, when newspaper editors are starved of ‘serious’ stories, is to announce that the Internet is like the Wild West, and children are constantly exposed to unsuitable material on YouTube, reveal intimate personal details on Bebo and surf the web looking for pro-anorexia or suicide support sites.

Sadly, it seems that John Whittingdale and his committee members have not been poring over the technical details of IPv6 and OpenID, so what we’ve got in their report is yet more condemnation of the dark side of today’s Internet and a few poorly-grounded suggestions as to what might be done, most of which seem to comprise a call for Internet service providers and web hosts to become the net’s new morality police.

I’ve just caught up with David Miliband’s article, which is refreshing because it’s about ideas rather than the brain-dead media obsession with Brown’s personality. I liked this passage:

With hindsight, we should have got on with reforming the NHS sooner. We needed better planning for how to win the peace in Iraq, not just win the war. We should have devolved more power away from Whitehall and Westminster. We needed a clearer drive towards becoming a low-carbon, energy-efficient economy, not just to tackle climate change but to cut energy bills.

But 10 years of rising prosperity, a health service brought back from the brink, and social norms around women’s and minority rights transformed, have not come about by accident. After all, the Tories opposed almost all the measures that have made a difference — from the windfall tax on privatised utilities to family-friendly working.

Now what are they offering? The Tories say society is broken. By what measure? Rising crime? No, crime has fallen more in the past 10 years than at any time in the past century. Knife crime and gun crime are serious problems. But since targeting the spike in gun crime, it has been cut by 13% in a year, and we have to do the same with knife crime.

What about the social breakdown that causes crime? More single parents dependent on the state? No, employment has risen sharply for lone parents because the state has funded childcare and made work pay. Falling school standards? No, they are rising. More asylum seekers? No, we said we would reform the system and slash the numbers, and we did…

That’s a start. It’s nice to see a Labour bigwig express some regrets. But he doesn’t go far enough. No serious mention of the decision to go to war in Iraq, for example (just regret that there wasn’t more planning for the aftermath). No appreciation of the fundamental weaknesses of Labour’s approach to the public services — in particular its crazed obsession with ‘targets’. And then there’s the government’s innate authoritarianism, its insistence on detention without charge or trial, its determination to have an ID card system and its relentless extension of the powers of surveillance. Miliband’s willingness to admit to weakness and maybe even of error is a welcome change, but it looks like pretty feeble stuff to me.

Now if there were to be a putsch that unhorsed Brown, and if the new leader were really to make a clean break with the past in relation to the above list, then it would pull the rug from under the Cameroonians, and might even cause the electorate to rub its collective eyes in amazement — and interest. But I can’t see it happening.

Sunder Katwala (Secretary of the Fabian Society) has some critical comments on the Miliband article.

Nice piece of literary fantasy in his week’s Economist, which has been wondering if Gordon Brown has a future.

He decided to ring Downing Street. No, his chief of strategy told him, there had been no outbreaks of agricultural disease that might require him to convene a COBRA emergency meeting. No, they were not expecting any abnormal weather that would oblige him to rush back to London. Try to relax, prime minister, the strategist said.

He tried. He went down to the beach and made a sandcastle, carefully planting a miniature Union Jack on top of it, endeavouring not to think about the perfidy of the voters in the Glasgow East by-election and the deluded nationalism of his Scottish countrymen. Finally he rolled up his trousers and waded into the surf, looking out moodily across the grey and choppy waters. His mind flitted between love, fate, betrayal, the decline of North Sea mackerel stocks and the Icelandic cod war of 1958. For a moment, he felt at peace. He loosened his tie.

Sunset in Donegal, around 10pm last night.

Hooray! George Orwell’s diaries are being published online, starting on August 9.

And, yeah, I know it’s a cod postcard cliché, but what the hell. It actually happened today.

We made our annual pilgrimage to W.B.’s grave today, partly because it’s an excuse to visit a beautiful (and IMHO under-rated) part of Ireland, but also because Drumcliffe is a lovely churchyard lying, as it does, at the foot of Ben Bulben.

By Church of Ireland (i.e. Protestant) standards, it’s an extraordinarily well-preserved and maintained churchyard, with fascinating name juxtapositions, as here:

And just along from Wagner, what do we find?