Alexander Solzhenitsyn has died aged 89.

What happened?

Hmmm… Funny that McCain should be attacking Obama for his youth and inexperience…

Ads or no ads?

In the chapter on publishing in his forthcoming book, Jeff Jarvis writes this:

So here’s the question: Why shouldn’t books have ads to support them as TV, newspapers, magazines, and radio do? Ads in books would be less irritating than commercials interrupting shows or banners blinking at you on a web page. Would it be any more corrupting to have ads in this book than next to a story I write in Business Week? Well, you’d have to tell me. If I were to have had a sponsor or two for this book, who would it have been and what would you have thought of my work as a result? If Dell bought an ad—because, after all, I now have nice things to say about them—would you have wondered whether I’d sold out to them? I would fear you’d think that. What about Google itself? Obviously, that wouldn’t work. Yahoo? Ha! Who might want to talk to you and associate themselves with the thinking in this book while also helping to support it? I’m not sure. Let’s discuss that for the paperback I hope gets published. Come to my blog and tell me what you think.

In an interesting blog post he asks

Do you think I should take a sponsor or two for the book (I’m not saying it’s an option; this is a discussion)? If so, who would make a good sponsor? Who wouldn’t? Would it affect your thinking if a sponsored book cost less? Should I then wish for a sponsor not only because it reduces the risk for the publisher and me but because it means more books could be sold at a lower price spreading the ideas in the book farther?

It’s worth reading the post in full because it attracted a good many thoughtful comments from readers, most of whom were sceptical.

The ads on Jeff’s blog at the time constituted such a nice counterpoint to the discussion in the text that I just had to clip the image!

On the beach

This is where I spent last Sunday — on the beach at Naran. There were all kinds of exciting proposals for what we should do that day, and the others went off on cycle rides and other energetic pursuits. But I just got a folding chair and a book and sat on the beach. And, in the end, I didn’t do much reading, but simply sat there watching and listening and drinking in the scene.

I fell to wondering what it is that is so satisfying about beach holidays. Partly it’s because they’re perfect for families with young children — especially when the beach is as gentle and safe as this. At one stage a nice young couple and their toddler arrived and came past me. The child had clearly just begun to walk, and I watched, enthralled, as she tottered determinedly, hands outstretched, towards the sea with her proud (and slightly anxious) parents following in her wake. And I remembered how Sue and I used to sigh with relief when we came on such a place when our children were young: we could set up a base with rugs and towels and drinks and the kids could roam without us having to worry about their safety. We could even snatch a moment or two to read, or just to talk quietly together. But now the kids are grown up and independent, and still I choose to be here. Why?

One answer is that this is what I craved when I was a child myself. I envied families who had seaside houses. But my parents weren’t ones for beach holidays. They believed in shuttling from relative’s house to relative’s house over the holiday period. Given that they both came from large families, this made for a lot of time on the move. In fact, the only time I can ever remember a long period on a beach with them was a blissful June day we spent at Portnoo — the next beach along this Donegal coast — when I was seven or eight. I remember the water being temperate (and the waves gentle, as they were last Sunday), the sandwiches delicious, and tea (brewed on a Primus stove) tasting like tea never tasted at home. And because it’s light until nearly 11pm in June in this part of the world, the day seemed to go on forever. I remember thinking that this is how I always wanted summers to be. But they never were.

Until now. However, I reflected, getting up to fetch a (delicious) cup of tea from the cafe at the end of the rudimentary promenade, better late than never.

Six degrees of texting

From BBC NEWS…

A US study of text messages suggests the theory that we are all linked by six steps to anyone else may be right – though seven seems more accurate.

Microsoft researchers studied the addresses of 30bn text messages sent during a single month in 2006.

Any two people on average are linked by seven or fewer acquaintances, they say…

Wonder if this is the first study to be done on a global rather than a society-wide basis? Also, it rather undermines the conjecture — which I first saw, I think, in the Economist — that electronic connectivity was reducing the Milgram coefficient.

Poorly chestnuts

I love Horse chestnut trees, and so am worried by the fact that many of them appear to be ailing — at least in East Anglia. From a distance, they look as though they’re going brown, as if Autumn has arrived suddenly and early. Close-up, their leaves are mottled like this.

Here’s the culprit: a ‘leaf-mining’ moth called Cameraria ohridella. According to the Forestry Commission, the damage is caused by its larvae. “The spread and establishment of C. ohridella is of particular concern”, it says, “because once established, the moth appears always to maintain exceptionally high rates of infestation without any evidence of decline. In European towns and cities there has been no decrease in populations even after many years, and severe damage to horse chestnuts has occurred on an annual basis, greatly impairing the visual appearance of the trees”.

When ignorance is bliss

This morning’s Observer column…

Sometimes, ignorance is bliss. We saw two examples of this last week. The first came when a new search engine – Cuil (www.cuil.com) – was unveiled. The launch was an old-style PR operation. Some influential bloggers and mainstream reporters had been briefed in advance, and whispers were circulating in cyberspace that this would be Something Big. Cuil would be the ‘Google Killer’ everyone had been waiting for.

Evidence for this hypothesis was freely cited. The venture was the brainchild of ‘former Google employees’: nudge, nudge. At least one of them had been at Stanford, the university that nurtured the founders of both Yahoo and Google: wink, wink. It had indexed no fewer than 121 billion web pages, compared with Google’s measly 40 billion: Wow! Cuil had already received $33m in venture funding! Cue trumpets.

So many people were taken in by this that when cuil.com finally opened for business the site was swamped…

Simply red

Facing down

Spotted in a friend’s garden.

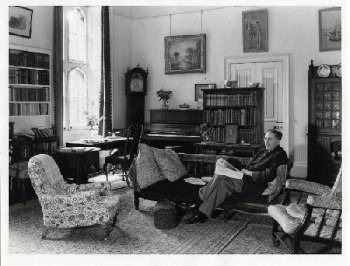

The middling way

One of the highlights of my student career was meeting E.M. Forster. Carol (my first wife) and I were members of the Cambridge Humanists, and the society threw a party for Forster on his 90th birthday. It was held in King’s, where he was a Life Fellow (the photograph, taken in 1968, shows him in his Set) and hosted by Francis Crick who — as a Nobel laureate — was Cambridge’s most prominent humanist at the time (and may even have been the society’s Patron). Forster was in a chair (it may have been wheelchair — on that my memory is foggy) and sat quietly while a good deal of celebratory bedlam — which he viewed with a mildly quizzical expression — went on around him.

As someone whose pet hate is people who are endowed with certainty: religious fundamentalists, for example and ideological fanatics — I’ve always admired Forster for his uncertainty, open-mindedness and willingness to entertain the thought that he might be wrong. So the works of his that I’ve enjoyed most have been his essays, and the broadcast talks he gave on the BBC. Which is why it’s wonderful to discover that the collected talks have now been published in a handsome, footnoted edition.

Zadie Smith (whose novel On Beauty was allegedly inspired by Forster’s Howard’s End) has written a thoughtful review in the current issue of the New York Review of Books. “In the taxonomy of English writing”, she writes,

E.M. Forster is not an exotic creature. We file him under Notable English Novelist, common or garden variety. Still, there is a sense in which Forster was something of a rare bird. He was free of many vices commonly found in novelists of his generation—what’s unusual about Forster is what he didn’t do. He didn’t lean rightward with the years, or allow nostalgia to morph into misanthropy; he never knelt for the Pope or the Queen, nor did he flirt (ideologically speaking) with Hitler, Stalin, or Mao; he never believed the novel was dead or the hills alive, continued to read contemporary fiction after the age of fifty, harbored no special hatred for the generation below or above him, did not come to feel that England had gone to hell in a hand-basket, that its language was doomed, that lunatics were running the asylum, or foreigners swamping the cities.

Smith’s angle is that Forster was the ultimate middleman. He was, she thinks,

a tricky bugger. He made a faith of personal sincerity and a career of disingenuousness. He was an Edwardian among Modernists, and yet—in matters of pacifism, class, education, and race—a progressive among conservatives. Suburban and parochial, his vistas stretched far into the East. A passionate defender of “Love, the beloved republic,” he nevertheless persisted in keeping his own loves secret, long after the laws that had prohibited honesty were gone. Between the bold and the tame, the brave and the cowardly, the engaged and the complacent, Forster walked the middling line.

I’ve always thought of him as the epitomé of mild common sense. He understood the primacy of friendship, for example, and his aphorism about it (that if he had to choose between betraying his country and betraying his friend he hoped he’d have the courage to do the former) is a pretty good guide for living. And, when one remembers the jingoistic times in which he said that, it’s a aphorism that took courage to articulate.

In fact, he’s always seemed to me to be, in his mild-mannered way, rather courageous. He was a distinguished humanist, but one who recognised that the creed had its weaknesses: “the humanist shirks responsibility”, he wrote, “dislikes making decisions, and is sometimes a coward”. But during the war and the years running up to it Forster didn’t display much cowardice. He ridiculed Nazi “philosophy” from the early 1930s onward, attacked the prison and police systems, defended the Third Program, spoke up for mass education, the rights of refugees, free concerts for the poor, and art for the masses. In other words, he kept faith with liberal principles that many of his more cocksure contemporaries abandoned. “Do we, in these terrible times”, he asked, “want to be humanists or fanatics? I have no doubt as to my own wish, I would rather be a humanist with all his faults, than a fanatic with all his virtues.”

Right on.