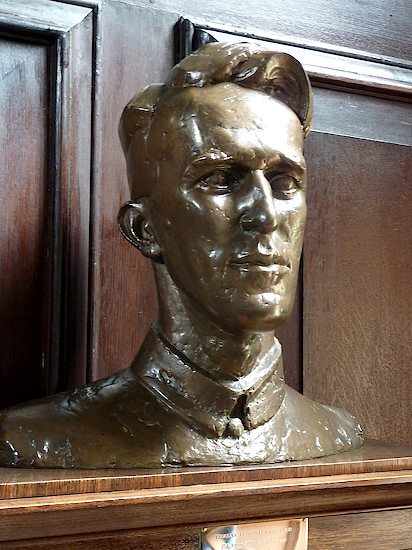

I spent an enjoyable day last week in Oxford with one of my boys, who is applying to go there to read medicine. After he’d done the dutiful things (attending talks in the Department of Medical Sciences, looking over some of the colleges he’s interested in, etc.) I asked him if it’d be ok if we ventured down memory lane. And so we went looking for this bust of T.E. Lawrence in the chapel of Jesus College.

I hadn’t seen it since one glorious late-August day in 1967 when I had visited Oxford for the first time. The whole place was deathly quiet (this was before the tourist boom) and the colleges, in particular, seemed like magical oases of scholarly peace. I had been reading The Seven Pillars but hadn’t known of Lawrence’s connection with Jesus (the college, that is. I later found that he had written a thesis on Crusader castles during his time there.) So the bust came as a delightful shock. Having grown up in the Ireland of the 1950s, a society which was not in the habit of honouring writers and in which James Joyce was still reviled as a pornographer, I was very struck — and touched — by it. And it led me to a critical decision that shaped my life.

At the time I was about to embark on the final year of my undergraduate engineering degree in Ireland. Insofar as I had a forward plan, it was to go to the US — maybe to MIT or to Berkeley. But sitting there in the sunlight shafting through the chapel windows on that peaceful August afternoon, I decided that I’d like to go to Oxford or Cambridge instead. In the end, I applied to both, and Cambridge made me an offer first. The rest, as they say, is (personal) history. It’s strange to rediscover the hinges on which one’s life turns. We lurch from one chance event to another, and then later on try to impose some kind of retrospective order on it. But in fact it’s more like what mathematicians call a ‘random walk’.

Flickr version here.