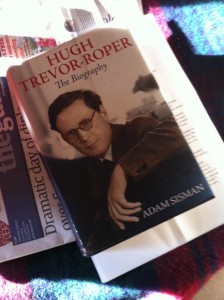

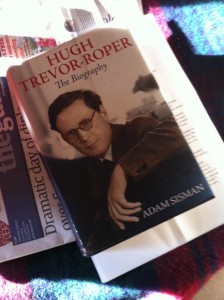

I’ve just finished Adam Sisman’s magnificent biography

I’ve just finished Adam Sisman’s magnificent biography of Hugh Trevor-Roper. It seems to me to be a model of its kind – knowledgeable, properly referenced, sympathetic without being sycophantic and extremely readable. And it caused me to revise my opinion of its subject. I’ve always been interested by Trevor-Roper, partly because I’ve been fascinated by history since I was a kid (it was a toss-up whether I would read history or engineering when I first went to university) and by historians (some of my best friends are practitioners of that craft). But I was particularly intrigued by T-R because of his literary style — which was waspish and mischievous to a degree rare even among historians. (Reading their observations of one another’s failings always reminds me of Evelyn Waugh’s observation that “the only virtue schoolboys demand from one another is humility”.)

of Hugh Trevor-Roper. It seems to me to be a model of its kind – knowledgeable, properly referenced, sympathetic without being sycophantic and extremely readable. And it caused me to revise my opinion of its subject. I’ve always been interested by Trevor-Roper, partly because I’ve been fascinated by history since I was a kid (it was a toss-up whether I would read history or engineering when I first went to university) and by historians (some of my best friends are practitioners of that craft). But I was particularly intrigued by T-R because of his literary style — which was waspish and mischievous to a degree rare even among historians. (Reading their observations of one another’s failings always reminds me of Evelyn Waugh’s observation that “the only virtue schoolboys demand from one another is humility”.)

It’s not surprising that Waugh came to mind. For one thing, he hated T-R because of his hostility to Catholicism. But Waugh also had the same kind of wickedly sarcastic prose style. Witness his observation when an acquaintance announced in White’s one day that surgeons had operated on Randolph Churchill (an authentic Grade One monster if ever there was one) to remove a tumour that had then been found to be benign. “Ah”, said Waugh, “the wonders of medical science: to have found the only part of Randolph that was not malignant — and to have removed it!.”

T-R shared another characteristic with Waugh in that both combined acute snobbery with assiduous social climbing: they both came from middle-class backgrounds and envied folks with what they regarded as better pedigrees. (When someone once tried to cheer Waugh up by reminding him that one of his ancestors had been ennobled in an act of political patronage, he responded that he would like to have been descended from a “useless peer”.)

Since Waugh was a deeply unpleasant person, I had always assumed that Roper must also have been similarly obnoxious. That impression was reinforced by reading his collected letters to Bernard Berenson, which are often hilarious, but also riddled with revolting sycophancy towards the old fraud.

to Bernard Berenson, which are often hilarious, but also riddled with revolting sycophancy towards the old fraud.

Adam Sisman’s book has made me revise that impression. He reveals that T-R seems to have had a real gift for friendship, that he could be very loyal, principled and courageous at times and that he was generous with his time and support for his students and protégés. Sisman also illuminates one of the great mysteries of T-R’s life, which is how someone who was so gifted never managed to produce the magnum opus that most people expected of him. The answer seems to be that he allowed himself constantly to be diverted by interesting journalistic projects, most of which stemmed from the fact that, early in his career, he had written a masterly, definitive account of the last days of Hitler. As an academic who has often been similarly distracted by journalism, I rather empathised with that predicament!

of the last days of Hitler. As an academic who has often been similarly distracted by journalism, I rather empathised with that predicament!

The Last Days of Hitler is a wonderful piece of factual journalism, which I would recommend to anyone aspiring to practice that grisly trade. Since most of us never produce anything as good as that, T-R can be forgiven a lot. But in a way the most illuminating part of Sisman’s book comes towards the end, when he deals with T-R’s time as Master of Peterhouse and his catastrophic error of judgement in authenticating the “Hitler diaries”. I know something of his time at Peterhouse, but hadn’t fully realised how courageous and effective he was in dealing with what was, at that time, the nastiest nest of donnish vipers in Oxbridge. No doubt some of Sisman’s chronicle had to be toned down because of the libel laws, so we can look forward to an unexpurgated second edition when the last of the aforementioned vipers has passed to his reward in Hell.

I was unexpectedly moved by the Hitler Diaries fiasco as recounted by Sisman. It was, of course, a catastrophe for T-R, and a mighty boon for all those who had, over the years, had to endure the sharp end of his wit. But what is impressive in retrospect is the courageous way he shouldered the blame and the ridicule — in sharp contrast to Murdoch and his minions who mostly tried to dodge their responsibility for the error. It’s not often that a book makes one change one’s mind. But this one did.