The idea that Google searches, tweets and Facebook ‘likes’ can be useful predictors of trends, developments and movie ‘hits’ has captured the imagination of many hucksters and media ‘analysts’. For example, it seems that Google searches may be good predictors of influenza outbreaks. And some time ago there was an interesting paper by Sitaram Asur and Bernardo in which they analyzed 2.89 million tweets from 1.2 million users about 24 movies released over a three-month period. They concluded that the rate of Tweets could predict the success of movies prior to their release, and also spot sleeper movies that grew successful over time. They also concluded that the quality of the predictions was significantly better than any other measure such as the Hollywood Stock Exchange.

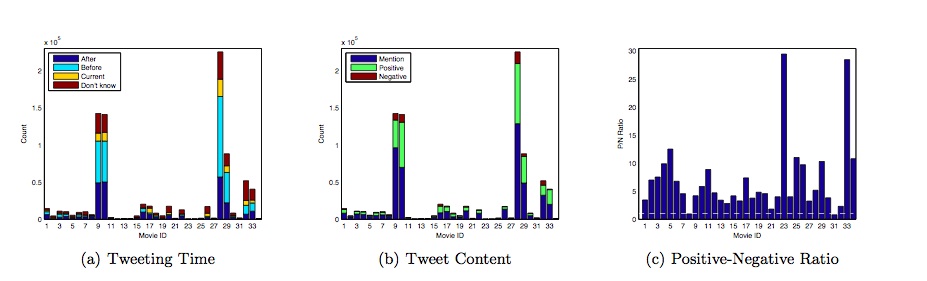

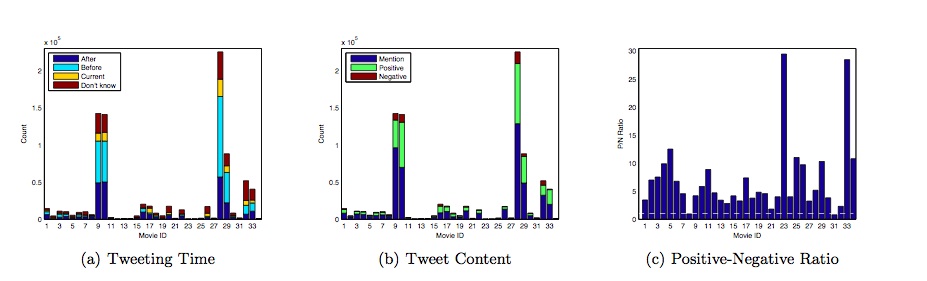

These findings seemed plausible to me. After all, if a large number of people are sharing thoughts about something (or expressing concerns via Google searches), then it would be reasonable to infer that data-mining will yield useful information. But now an interesting new study by some Princeton researchers suggests that a certain amount of scepticism might be in order. In a paper entitled “Why Watching Movie Tweets Won’t Tell the Whole Story?” [it’s not clear what the question-mark implies] Felix Ming Fai Wong, Soumya Sen and Mung Chiang question the idea that Twitter is a reliable predictor of the future, at least as far as winning Oscars and predicgint box office revenue are concerned. They collected 12 million tweets between February 2 and March 12 by tracking keywords related to recently-released or Oscar-nominated movies, classified them by relevance, sentiment and temporal context and analysed them for positive or negative sentiment. They then compared the resulting opinion statistics with sentiment about the same movies obtained from two conventional online review sites — iMDB and Rotten Tomatoes.

Their conclusions are interesting. They found that Twitter users are more likely to post positive views than negatives ones, and that views on Twitter do not necessarily correlate with those from the conventional sites. And — unlike Asur and Huberman — they seem unconvinced that Twitter sentiment is a good predictor of box-office revenue.

I suppose the only real conclusion to be drawn from this is that data-mining and “social physics” are not exact sciences. But then, we knew that anyway. Didn’t we?