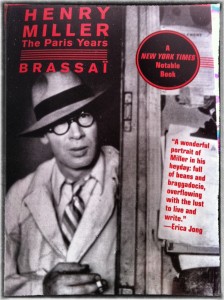

The Hungarian photographer, Brassai (whose real name was Gyula Halász), is one of my favourite artists (and a huge print of one of his most celebrated photographs — Les Escaliers de Montmartre — hangs in our dining room). But I had no idea he could write — until I stumbled on his book, Henry Miller: The Paris Years. It’s a startlingly illuminating and well-written book about a writer who was one of the photographer’s closest friends in Paris in the inter-war years, and who — until now — has always been an enigma to me.

Here’s how it opens:

“How does your memory of this compare with yours? I seem to see you standing in the Gutter at the Dome, a l’angle de la rue Delambre et Blvd Montparnasse… You had a newspaper in your hand. You told us you have begun to practice photography. It may have been the year 1931. The spot where you stood I see so vividly that I could draw a circle around it.” In a letter to me, this is how Henry Miller recalled our first meeting. “It’s strange”, he told me, “but with most people we remember neither where nor under shat circumstances we met. But I remember the first time you and I met as if it were yesterday.”

My memory doesn’t quite compare with his. My memory of the first time Henry and I met was that it took place in December 1930, shortly after he had arrived in France. My friend the painter Louis Tihanyi introduced us. Louis was sort of the Dome’s PR man — everyone recognised his olive green corduroy overcoat, worn to a shine, his wide-brimmed gray felt hat, his monocle, his fleshy lower lip. He was the spitting image of Alphonse XIII — minus the pencil mustache. Every night, table by table, Louis worked the crowded Dome terrace, which, beneath the luminous green shade of the trees on the boulevard, was always festive, as if every day were Bastille. Although deaf, and very nearly dumb as well, Louis was the best-informed man in Montparnasse. He knew not only every single one of the regulars, but the measure and worth of each newcomer.

“I want you to meet Henry Miller, an American writer,” he announced in his abrupt, guttural voice, which somehow always managed to make itself heard over the hum of conversation and the noise from the street”.

And there was Henry Miller. I will never forget the first sight of his rosy face emerging from a rumpled raincoat: the pouting, full lower lip, eyes the color of the sea. His eyes were like those of a sailor skilled at scanning the horizons through the spray. They always conveyed calmness and serenity, those eyes, and even though their expression seemed as guileless and attentive as a dog’s, they lay in ambush behind large tortoiseshell glasses…”.

I couldn’t put it down. It’s a fascinating blend of insight, affection, forgiveness and acuity. And, like Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast and Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris

, it’s beautifully evocative of an astonishing period in the life of my favourite city.