On this morning, 80 years ago, World War II started. It was a Sunday too.

The downside of tech platforms

This morning’s Observer column:

But because capitalism never knows when to stop, eventually even the exponential growth rate promised by Metcalfe’s law wasn’t good enough for Google and co. They noticed Reed’s law, which said that if a network can have sub-groups then its utility can grow at an even more colossal rate. And so they began to turn themselves into platforms on which entrepreneurs could build services. A platform in this sense is a set of tools provided by the owner to enable third-party developers to create applications that interact with core features of the platform (thereby keeping users within the network to leave monetisable data trails)…

Quote of the Day

”I often wonder whether we do not rest our hopes too much upon

constitutions, upon laws and upon courts. These are false hopes; be-

lieve me, these are false hopes. Liberty lies in the hearts of men and

women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save

it; no constitution, no law, no court can even do much to help it.”

Is this Britain’s ‘Reichstag Fire’ moment?

Sobering assessment in Prospect by Richard Evans:

But if Hitler’s rise teaches us anything, it’s that the establishment trivialises demagogues at its peril. One disturbing aspect of the present crisis is the extent to which mainstream parties, including US Republicans and British Conservatives, tolerate leaders with tawdry rhetoric and simplistic ideas, just as Papen, Hindenburg, Schleicher and the rest of the later Weimar establishment tolerated first Hitler and then his dismantling of the German constitution. He could not have done it in the way he did without their acquiescence. Republicans know Trump is a charlatan, just as Conservatives know Johnson is lazy, chaotic and superficial, but if these men can get them votes, they’ll lend them support.

Weimar’s democracy did not exactly commit suicide. Most voters never voted for a dicatorship: the most the Nazis ever won in a free election was 37.4 per cent of the vote. But too many conservative politicians lacked the will to defend democracy, either because they didn’t really believe in it or because other matters seemed more pressing. As for rule by emergency decree, few people thought Hitler was doing anything different from Ebert or Brüning when he used Hindenburg’s powers to suspend civil liberties after the Reichstag Fire on 28th February 1933. That decree was then renewed all the way up to 1945. In this sense, democracy was destroyed constitutionally.

Which is exactly what’s going on in the UK at the moment.

The lesson, says Evans,

seems to be that to prevent the collapse of representative democracy, the legislature must jealously guard its powers. Can we rely on that happening today? It doesn’t help that the British parliament, as was its counterpart in Weimar, has become more or less paralysed on the most important issue of the day. As in Weimar, the only majorities are negative ones—against, for example, Theresa May’s Brexit deal as well as, so far at least, every available alternative.

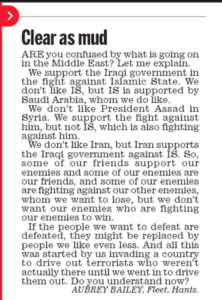

UK foreign policy, in a nutshell

So what happens to urban traffic if we get self-driving cars?

Answer: our streets become much more congested. This thought-provoking post comes from Quartz:

Researchers at the University of California, Davis and UC-Berkeley gave a test group free private drivers to see what would happen when people get self-driving cars. Vehicle usage soared by 83%. That’s a potential nightmare in traffic-choked metropolitan areas, where increased travel could erase the efficiency gains of the last fifty years.

The outlines of this future are coming into focus in San Francisco. Between 2010 and 2016, congestion in the city rose by about 60%, city officials estimate. Half of this was attributed to Lyft and Uber as more people took ride-hailing services instead of transit and other non-car forms of transportation. Cars driving around waiting for passengers to hail them added to the problem, especially in congested areas of the city.

City planners say that to ease congestion, it’s key to keep private AVs on the periphery of dense urban centers, and focus on public transit and last-mile solutions at the center. If “personally-owned automated vehicles are superimposed on today’s patterns of usage… that will lead to the hell scenario,” says Daniel Sperling, founder of the Institute of Transportation Studies at UC-Davis. What, then, would heaven look like? “UberPool without the driver.”

This is interesting because AV-evangelists are always saying that self-driving cars will make our cities more pleasant.

Sauce for the goose…

The staff (and proprietor) of the New York Times have their knickers in a twist because some right-wingers have been excavating embarrassing or foolish tweets that NYT journalists have emitted in the past. Jack Shafer is having none of it:

Deep scrutiny of the press—even when performed by bad faith actors like Arthur Schwartz and his ilk—is a boon, not a bane. The embarrassments unearthed by Schwartz and company will bruise the tender egos who run the Times, the Post and CNN. But in the long run, these minirevelations will help them maintain the professional standards they’re always crowing about. Instead of damning its critics for going through its staffs’ social media history with tweezers, the Times and A.G. Sulzberger should send them a thank you card.

Yep. American journalism can be very pompous at times.

Quote of the Day

”If intelligence is a cake, the bulk of the cake is unsupervised learning, the icing on the cake is supervised learning, and the cherry on the cake is reinforcement learning.”

Where is the understanding we lose in machine learning?

This morning’s Observer column:

Fans of Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy treasure the bit where a group of hyper-dimensional beings demand that a supercomputer tells them the secret to life, the universe and everything. The machine, which has been constructed specifically for this purpose, takes 7.5m years to compute the answer, which famously comes out as 42. The computer helpfully points out that the answer seems meaningless because the beings who instructed it never knew what the question was. And the name of the supercomputer? Why, Deep Thought, of course.

It’s years since I read Adams’s wonderful novel, but an article published in Nature last month brought it vividly to mind. The article was about the contemporary search for the secret to life and the role of a supercomputer in helping to answer it. The question is how to predict the three-dimensional structures of proteins from their amino-acid sequences. The computer is a machine called AlphaFold. And the company that created it? You guessed it – DeepMind…

Quote of the Day

”History is the sum total of things that could have been avoided”

Konrad Adenauer