Quote of the Day

“The nature of things is a sturdy adversary”

- Edmund Burke

Reminds me of the famous reply Harold Macmillan gave to a reporter who asked him what kept him awake at nights: “Events, dear boy, events”.

Musical alternative to this morning’s radio news

Eric Clapton: Cocaine — at the Albert Hall

Slow and enigmatic start. Worth waiting for, though.

The Social Dilemma: a wake-up call for a world drunk on dopamine?

This morning’s Observer column.

TL;DR version: the new Netflix docudrama is a valiant if flawed attempt to address our complacency about surveillance capitalism.

Spool forward a couple of centuries. A small group of social historians drawn from the survivors of climate catastrophe are picking through the documentary records of what we are currently pleased to call our civilisation, and they come across a couple of old movies. When they’ve managed to find a device on which they can view them, it dawns on them that these two films might provide an insight into a great puzzle: how and why did the prosperous, apparently peaceful societies of the early 21st century implode?

The two movies are The Social Network, which tells the story of how a po-faced Harvard dropout named Mark Zuckerberg created a powerful and highly profitable company; and The Social Dilemma, which is about how the business model of this company – as ruthlessly deployed by its po-faced founder – turned out to be an existential threat to the democracy that 21st-century humans once enjoyed.

Both movies are instructive and entertaining, but the second one (which has just been released on Netflix) leaves one wanting more. Its goal is admirably ambitious: to provide a compelling, graphic account of what the business model of a handful of companies is doing to us and to our societies. The intention of the director, Jeff Orlowski, is clear from the outset: to reuse the strategy deployed in his two previous documentaries on climate change – nicely summarised by one critic as “bring compelling new insight to a familiar topic while also scaring the absolute shit out of you”.

For those of us who have for years been trying – without notable success – to spark public concern about what’s going on in tech, it’s fascinating to watch how a talented movie director goes about the task…

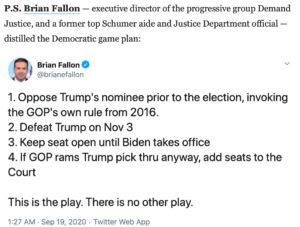

What to do if Trump and the Republicans in the Senate ram through a new Supreme Court nominee.

Interesting. I hadn’t known that the number of Supreme Court justices is not stipulated by the Constitution. That means an Act of Congress could change it.

Johnson’s not up to the job. Who knew?

It’s funny how many people seem still to be astonished by the incompetence of the Johnson administration. Given his record as a lazy, irresponsible toff who has all his life left behind him a wake of chaos, unhappiness and offspring, what else could one expect? Andrew Rawnsley has a nice column about this in today’s Observer. Here’s its conclusion:

Funnily enough, the book Superforecasting [which Dominic Cummings reviewed enthusiastically put on his reading list for ministers] identifies one of the core reasons why this government is failing. “The worst forecasters were those with great self-confidence who stuck to their big ideas,” wrote Mr Cummings himself. They are lousy at understanding the world and coming to good judgments about it. “The more successful were those who were cautious, humble, numerate, actively open-minded, looked at many points of view.” Now, which is a better description of the Johnson-Cummings method of government? “Cautious, humble, numerate, actively open-minded, looked at many points of view”? That doesn’t sound like them at all. “Great self-confidence”, which leaves them stubbornly wedded to their “big ideas”? That’s much more like it.

Their biggest idea of the moment is that leaving the EU’s single market without a deal would be fine even in a double-whammy combination with a re-escalation of the coronavirus crisis. Bear in mind his previous record as a soothsayer when the prime minister confidently predicts that a crash-out Brexit would be a “good outcome”. I hazard a guess that this is his most calamitously wrong forecast of all.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!