- YouTube Is Experimenting With Ways to Make Its Algorithm Even More Addictive

- Academics protest as Cambridge fellow told to leave Britain

- Boris Johnson’s Conservative party has received cash from 9 Russian donors named in a suppressed intelligence report Funny, that. The Tories used to be the anti-Russia party. Corbyn was supposed to be Putin’s stooge. How times change.

- Three Eras of Digital Governance Useful essay by the Harvard scholar Jonathan Zittrain summarising how we’ve got to our current impasse about Internet regulation.

Monthly Archives: November 2019

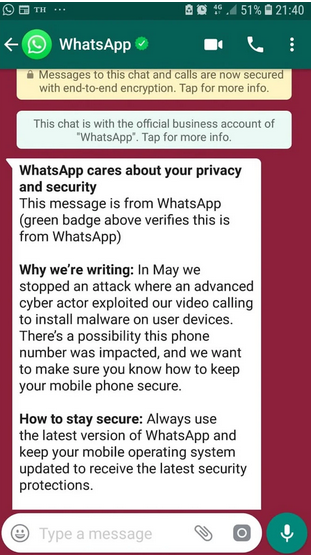

Why WhatsApp might be suing NSO

Screenshot of the message from WhatsApp to Nihalsing Rathod, a lawyer representing some of the activists accused of fomenting a protest last year in Bhima Koregaon, in India, and plotting to kill Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2017. The message is alerting him to the fact that WhatsApp suspect that his smartphone has been infected with NSO spyware.

British politics, circa 2019

From a splendid column by Marina Hyde on the current ‘election’ campaign:

On the subject of presumably competitively priced after-dinner speakers, what a week to learn that Theresa May has been signed up to the circuit, believed to have fought off a bid from the speaking clock for her services. May bills herself as a specialist in “inspiring lives” and how to “achieve progress”. Why not just add election-winning and contemporary streetdance? In for a penny; in for an unspecified number of pounds an hour. The news did seem to confirm that irony-manufacture is our sole thriving industry.

Or this:

Elsewhere, imbecility remains a key battleground, with debate over which party is fielding the more extravagantly or malevolently stupid candidates. Is it the Tories, whose children and families minister Nadhim Zahawi insisted he wasn’t sure whether Jeremy Corbyn would shoot the rich, adding: ”You’ll have to ask him that question”? Or is it Labour, whose newly selected Pudsey candidate Jane Aitchison provided the BBC’s Emma Barnett with 12.5 seconds of dead air in a discussion in which she apparently excused another candidate saying she’d celebrate the death of Tony Blair. It was one of those clips you listen to going, “Don’t say Hitler. Don’t say Hitler. Don’t say Hitler. Don’t say Hitler.” “For instance,” reasoned Jane, “they celebrated the death of Hitler.”

Only in a field like this could Boris Johnson retain a reputation as an orator. The best way to get through a Johnson speech is tell yourself he’s going to make 10 jokes he’s done numerous times before, then it won’t be so bad when he only does nine. His three-and-a-half minute campaign launch set in Birmingham saw a return for several “old friends”. Yet again, Johnson produced his line about broadband being “informative vermicelli”, as though he were Taylor Swift and he had to do Shake it Off because that’s what the crowd had come for. “This is a prime minister on fire,” judged Gavin Williamson, who seems to be back in the fireplace selling business.

Linkblog

- From Pseudoevents to Pseudorealities Marvellous lecture by Renee DiResta on propaganda from Walter Lippmann’s time to the present. Puts ‘fake news’ into an intelligent historical context.

- I Accidentally Uncovered a Nationwide Scam on Airbnb Fascinating account of a large-scale scam and on Airbnb’s strange inability to deal with it.

- WhatsApp sues Israeli firm, accusing it of hacking activists’ phones Interesting lawsuit against the Israeli company NSO. The suit is funded by Facebook, which has deep enough pockets to see it through.

- This Is No Ordinary Impeachment Terrific column by Andrew Sullivan about what’s at stake in the Impeachment hearings.

Dream vs. emerging reality

The new Cavendish Lab is beginning to emerge from the bowels of the earth. Hard to see how the current crane-fest will result in the nice pic on the hoarding. To date, Cavendish researchers have won 30 Nobel prizes.

DNA databases are special

This morning’s Observer column:

Last week, at a police convention in the US, a Florida police officer revealed he had obtained a warrant to search the GEDmatch database of a million genetic profiles uploaded by users of the genealogy research site. Legal experts said this appeared to be the first time an American judge had approved such a warrant.

“That’s a huge game-changer,” observed Erin Murphy, a law professor at New York University. “The company made a decision to keep law enforcement out and that’s been overridden by a court. It’s a signal that no genetic information can be safe.”

At the end of the cop’s talk, he was approached by many officers from other jurisdictions asking for a copy of the successful warrant.

Apart from medical records, your DNA profile is the most sensitive and personal data imaginable. In some ways, it’s more revealing, because it can reveal secrets you don’t know you’re keeping, such as siblings (and sometimes parents) of whom you were unaware…

Linkblog

- Three Chinese lessons Riveting account of what it’s like to work in a Chinese tech company.

- Can Big Tech Be Tamed? Wonderful, long, essay by Gary Kamiya on what the tech industry has done to San Francisco. Best thing about it: he doesn’t go for simplistic answers.

- Unearthed photos reveal what happened to those who dared to flee through the Berlin Wall On the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the short film The Escape Agents is based a cache of photographs from security service records of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). Good way of marking the anniversary (which is today, by the way).

- The frat-boy lunacy behind the WeWork shambles

Kranzberg’s Law

As a critic of many of the ways that digital technology is currently being exploited by both corporations and governments, while also being a fervent believer in the positive affordances of the technology, I often find myself stuck in unproductive discussions in which I’m accused of being an incurable “pessimist”. I’m not: better descriptions of me are that I’m a recovering Utopian or a “worried optimist”.

Part of the problem is that the public discourse about this stuff tends to be Manichean: it lurches between evangelical enthusiasm and dystopian gloom. And eventually the discussion winds up with a consensus that “it all depends on how the technology is used” — which often leads to Melvin Kranzberg’s Six Laws of Technology — and particularly his First Law, which says that “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.” By which he meant that,

“technology’s interaction with the social ecology is such that technical developments frequently have environmental, social, and human consequences that go far beyond the immediate purposes of the technical devices and practices themselves, and the same technology can have quite different results when introduced into different contexts or under different circumstances.”

Many of the current discussions revolve around various manifestations of AI, which means machine learning plus Big Data. At the moment image recognition is the topic du jour. The enthusiastic refrain usually involves citing dramatic instances of the technology’s potential for social good. A paradigmatic example is the collaboration between Google’s DeepMind subsidiary and Moorfields Eye Hospital to use machine learning to greatly improve the speed of analysis of anonymized retinal scans and automatically flag ones which warrant specialist investigation. This is a good example of how to use the technology to improve the quality and speed of an important healthcare service. For tech evangelists it is an irrefutable argument for the beneficence of the technology.

On the other hand, critics will often point to facial recognition as a powerful example for the perniciousness of machine-learning technology. One researcher has even likened it to plutonium. Criticisms tend to focus on its well-known weaknesses (false positives, racial or gender bias, for example), its hasty and ill-considered use by police forces and proprietors of shopping malls, the lack of effective legal regulation, and on its use by authoritarian or totalitarian regimes, particularly China.

Yet it is likely that even facial recognition has socially beneficial applications. One dramatic illustration is a project by an Indian child labour activist, Bhuwan Ribhu, who works for the Indian NGO Bachpan Bachao Andolan. He launched a pilot program 15 months prior to match a police database containing photos of all of India’s missing children with another one comprising shots of all the minors living in the country’s child care institutions.

The results were remarkable. “We were able to match 10,561 missing children with those living in institutions,” he told CNN. “They are currently in the process of being reunited with their families.” Most of them were victims of trafficking, forced to work in the fields, in garment factories or in brothels, according to Ribhu.

This was made possible by facial recognition technology provided by New Delhi’s police. “There are over 300,000 missing children in India and over 100,000 living in institutions,” he explained. “We couldn’t possibly have matched them all manually.”

This is clearly a good thing. But does it provide an overwhelming argument for India’s plan to construct one of the world’s largest facial-recognition systems with a unitary database accessible to police forces in 29 states and seven union territories?

I don’t think so. If one takes Kranzberg’s First Law seriously, then each proposed use of a powerful technology like this has to face serious scrutiny. The more important question to ask is the old Latin one: Cui Bono?. Who benefits? And who benefits the most? And who loses? What possible unintended consequences could the deployment have? (Recognising that some will, by definition, be unforseeable.) What’s the business model(s) of the corporations proposing to deploy it? And so on.

At the moment, however, all we mostly have is unasked questions, glib assurances and rash deployments.

Linkblog

- Who owns Silicon Valley? Apart from Stanford, that is?

- An interview with Stuart Russell on Artificial Intelligence Audio plus transcript. Russell’s book, Human Compatible is thoughtful and accessible. My review of it for the Literary Review is here.

- The Myth of the Nazi War Machine Amazing piece of factual research. Looks as though almost everything we thought we knew about German (and Japanese) military and industrial might is wrong. [See footnote]

- Former Twitter Employees Charged With Spying for Saudi Arabia Wonder how many Saudi moles there are in Facebook and YouTube.

Footnote A reader writes that my claim that “everything we thought we knew about German (and Japanese military and industrial might is wrong” applies only to those who haven’t read Adam Tooze’s * The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy*. I stand corrected.

Linkblog

- Inside Amazon’s plan for Alexa to run your entire life The re-engineering of humanity continues apace.

- List of the international brands that have apologised to China Hypocrisy or pragmatism? Is there any difference?

- Artificial Intelligence: How to get it right Terrific report, full of good sense.

- Down the Hunger Spiral: Pathways to the Disintegration of the Global Food System Nothing but alarming news: for a precarious global agricultural system with powerful feedback loops, business as usual means widespread hunger and embedded systemic risk. We kind-of realised that. But this is a very informed and systemic analysis.