James Fallows quotes from a fascinating email exchange he had with his friend Michael Jones, who used to work at Google (he was the company’s Chief Technology Advocate and later a key figure in the evolution of Google Earth):

So, how might FB fix itself? What might government regulators seek? What could make FaceBook likable? It is very simple. There are just two choices:

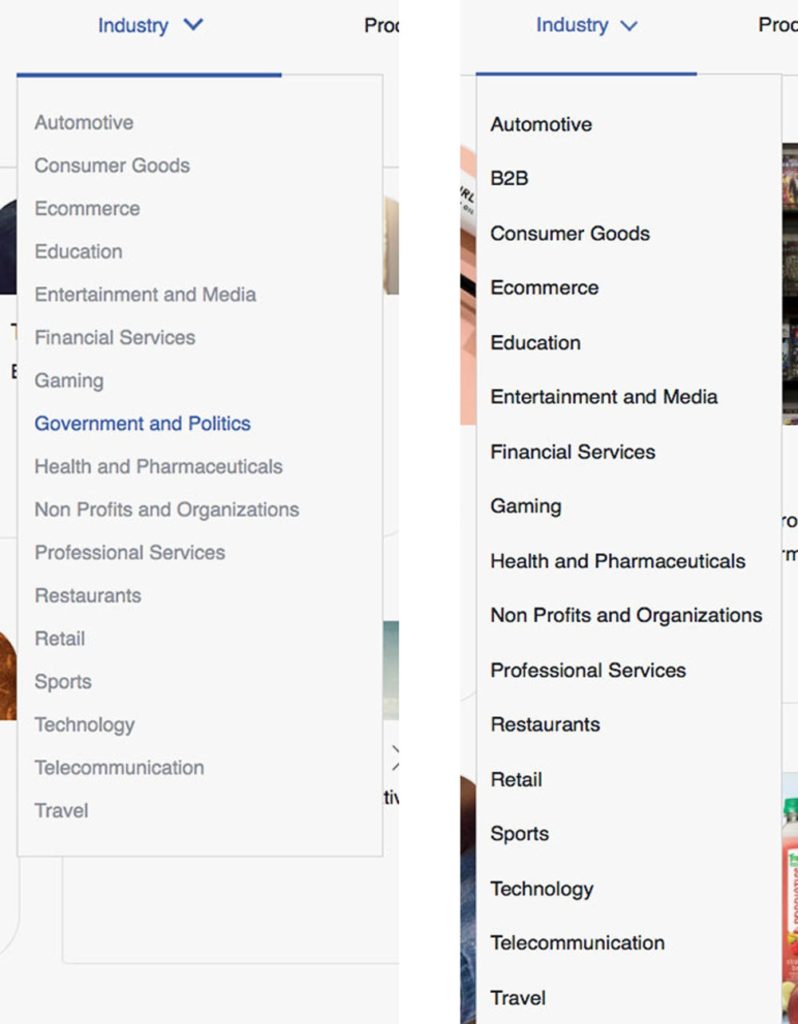

a. FB stays in its send-your-PII1-to-their-customers business, and then must be regulated and the customers validated precisely as AXCIOM and EXPERIAN in the credit world or doctors and hospitals in the HIPPA healthcare world; or,

b. FB joins Google and ALL OTHER WEB ADVERTISERS in keeping PII private, never letting it out, and anonymously connecting advertisers with its users for their mutual benefit.

I don’t get a vote, but I like (b) and see that as the right path for civil society. There is no way that choice (a) is not a loathsome and destructive force in all things—in my personal opinion it seems that making people’s pillow-talk into a marketing weapon is indeed a form of evil.

This is why I never use Facebook; I know how the sausage is made.

-

PII = Personally Identifiable Information ↩