Leave aside for the moment the mysterious role (and behaviour) of the FBI Director in the last week of the election campaign and focus for a moment on one aspect of the supporters of the two candidates — different levels of education. A few weeks ago my colleague David Runciman wrote this in the Guardian:

The possibility that education has become a fundamental divide in democracy – with the educated on one side and the less educated on another – is an alarming prospect. It points to a deep alienation that cuts both ways. The less educated fear they are being governed by intellectual snobs who know nothing of their lives and experiences. The educated fear their fate may be decided by know-nothings who are ignorant of how the world really works. Bringing the two sides together is going to be very hard. The current election season appears to be doing the opposite.

The headline on the essay was “How the education gap is tearing politics apart.”

Yesterday the FBI Director wrote to Congress saying that his staff had reviewed the relevant emails on Anthony Weiner’s laptop and found nothing that would cause the Agency to review its earlier judgment that there was no justification for taking action against Hillary Clinton.

Needless to say, this was meat and drink for Trump. “You can’t review 650,000 emails in eight days,” he said yesterday in an appearance at the Freedom Hill Amphitheater in Michigan.

“You can’t do it folks. Hillary Clinton is guilty. The investigations into her crimes will go on for a long, long time. The rank-and-file special agents at the FBI won’t let her get away with her terrible crimes, including the deletion of her 33,000 emails after receiving a congressional subpoena.”

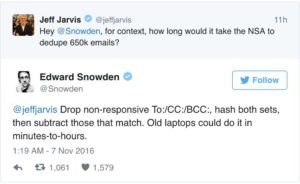

Needless to say, Trump’s supporters were delighted. Here’s a sample tweet:

There are only two conclusions to be drawn from this: (a) Trump knows nothing about computer technology; or (b) he does, but is reckoning that his supporter base knows nothing about it.

My hunch is (b), but it doesn’t really matter either way. The task of getting software to trawl through any number of electronic documents looking either for metadata (like “From:”. “To:” or “cc:”) or keywords is computationally trivial. Ask Edward Snowden:

In fact, as one expert pointed out the real question that the FBI Director should have to answer is: what took you so long?