Lovely New Yorker cover today!Note that it also blew the top of his top hat off.

Category Archives: Politics

The economic consequences of George Osborne

Last September there was a terrific conference in King’s College, Cambridge to celebrate the centenary of the publication of John Maynard Keynes’s famous pamphlet, The Economic Consequences of the Peace. In a mischievous spirit in the months before the event, I tried to persuade a well-known economist of my acquaintance to compose another pamphlet, The Economic Consequences of George Osborne, that we could unveil on the weekend before the Keynes conference.

Osborne, as most people know, was Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Coalition and Tory governments led by David Cameron following the 2010 general election. In that role he was the prime architect of the ‘austerity’ policy of slashing public expenditure (and therefore welfare benefits) using the preposterous rationale that somehow the public deficit brought about by rescuing the banks was due to extravagant spending by a Labour administration living beyond the country’s means. In fact, working on the principle that one should never let a good crisis go to waste, Osborne used this rationale as a cover for what he always had been seeking to do, namely to shrink the state in best Hayekian style.

Sadly, my tame expert was unable to help with the pamphlet, having been unexpectedly headhunted for a demanding role which left him little time for entertaining pursuits. So the booklet remained unwritten — until now.

But it has just surfaced under a different title and with a different set of authors. It’s Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On, written by a team led by Professor Sir Michael Marmot. Although the authors are much too polite and reserved to put it like this, the report shows that the consequences of George Osborne are as numerous and bleak as I had supposed. British subjects can expect to spend more of their lives in poor health, for example. Improvements to life expectancy have stalled, and declined for the poorest 10% of women. The health gap has grown between wealthy and deprived areas. And place really matters – living in a deprived area of the North East is worse for your health than living in a similarly deprived area in London, to the extent that life expectancy is nearly five years less.

In more detail, the research underpinning the report says:

- Since 2010 life expectancy in England has stalled; this has not happened since at least 1900. If health has stopped improving it is a sign that society has stopped improving. When a society is flourishing health tends to flourish.

- The health of the population is not just a matter of how well the health service is funded and functions, important as that is. Health is closely linked to the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age and inequities in power, money and resources – the social determinants of health.

- The slowdown in life expectancy increase cannot for the most part be attributed to severe winters. More than 80 percent of the slowdown, between 2011 and 2019, results from influences other than winter-associated mortality.

- Life expectancy follows the social gradient – the more deprived the area the shorter the life expectancy. This gradient has become steeper; inequalities in life expectancy have increased. Among women in the most deprived 10 percent of areas, life expectancy fell between 2010-12 and 2016-18.

- There are marked regional differences in life expectancy, particularly among people living in more deprived areas. Differences both within and between regions have tended to increase. For both men and women, the largest decreases in life expectancy were seen in the most deprived 10 percent of neighbourhoods in the North East and the largest increases in the least deprived 10 percent of neighbourhoods in London.

- There has been no sign of a decrease in mortality for people under 50. In fact, mortality rates have increased for people aged 45-49. It is likely that social and economic conditions have undermined health at these ages.

- The gradient in healthy life expectancy is steeper than that of life expectancy. It means that people in more deprived areas spend more of their shorter lives in ill-health than those in less deprived areas.

- The amount of time people spend in poor health has increased across England since 2010. As we reported in 2010, inequalities in poor health harm individuals, families, communities and are expensive to the public purse. They are also unnecessary and can be reduced with the right policies.

- Large funding cuts have affected the social determinants across the whole of England, but deprived areas and areas outside London and the South East experienced larger cuts; their capacity to improve social determinants of health has been undermined.

I could go on, but you will get the point.

Since being unceremoniously sacked by Theresa May, Osborne has led an exceedingly comfortable life, topping up the income from his family Trust Fund with a lavish salary as Editor of the London Evening Standard and £650,000 for working one day a week for the investment fund Blackwater.

Why socialism has had such a hard time in the US

“We didn’t have any self-admitted proletarians. Everyone was a temporarily embarrassed capitalist.”

Krugman on Bernie

From today’s NYT. He’s not overly impressed by Sanders, but…

I’m more concerned about (a) the electability of someone who says he’s a socialist even though he isn’t and (b) if he does win, whether he’ll squander political capital on unwinnable fights like abolishing private health insurance. But if he’s the nominee, it’s the job of Dems to make him electable if at all possible.

To be honest, a Sanders administration would probably leave center-left policy wonks like me out in the cold, at least initially. And if a President Sanders or his advisers say things I think are foolish, I won’t pretend otherwise in an attempt to ingratiate myself. (Sorry, I’m still not a convert to Modern Monetary Theory.) But this is no time for self-indulgence and ego trips. Freedom is on the line.

The real test of an AI machine? When it can admit to not knowing something

This morning’s Observer column on the EU’s plans for regulating AI and data:

Once you get beyond the mandatory euro-boosting rhetoric about how the EU’s “technological and industrial strengths”, “high-quality digital infrastructure” and “regulatory framework based on its fundamental values” will enable Europe to become “a global leader in innovation in the data economy and its applications”, the white paper seems quite sensible. But as for all documents dealing with how actually to deal with AI, it falls back on the conventional bromides about human agency and oversight, privacy and governance, diversity, non-discrimination and fairness, societal wellbeing, accountability and that old favourite “transparency”. The only discernible omissions are motherhood and apple pie.

But this is par for the course with AI at the moment: the discourse is invariably three parts generalities, two parts virtue-signalling leavened with a smattering of pious hopes. It’s got to the point where one longs for some plain speaking and common sense.

And, as luck would have it, along it comes in the shape of Sir David Spiegelhalter, an eminent Cambridge statistician and former president of the Royal Statistical Society. He has spent his life trying to teach people how to understand statistical reasoning, and last month published a really helpful article in the Harvard Data Science Review on the question “Should we trust algorithms?”

Ministers who can’t count

Pritti Patel, the current British Home Secretary (third from left, top row), recently introduced the UK’s “tough” new points-based immigration system that will come into force on January 1, 2021. Faced with criticism that the system will severely impair certain sectors of British industry, Ms Patel asserted that the new rules will be a golden opportunity for 8.48m “economically inactive” British people between the ages of 16 and 64 to join the workforce.

Writing in today’s Financial Times, Bronwen Maddox points out that, according to the Office of National Statistics, 2.3m of those are students, 2.1m are long-term sick or disabled, 1.9m are looking after their family or home, 1.1m are retired and 160,000 are temporarily sick. This leaves 1.87m who might like a job and do not have one.

Perhaps one of them would like a job in the Home Secretary’s office, handling the arithmetic.

Some historical perspective on the dominance of current tech giants

From this week’s Economist:

As big tech’s scope expands, more non-tech firms will find their profits dented and more workers will see their livelihoods disrupted, creating angry constituencies. One crude measure of scale is to look at global profits relative to American GDP. By this yardstick, Apple, which is expanding into services, is already roughly as big as Standard Oil and US Steel were in 1910, at the height of their powers. Alphabet, Amazon and Microsoft are set to reach the threshold within the next ten years.

Remember what happened to Standard Oil and US Steel?

If tech companies think they’re states, then they should accept the same responsibilities as states

It’s amazing to watch the deluded fantasies of tech bosses about their importance. In part, this is because their pretensions are taken seriously by political leaders who should know better. The daftest move thus far in this context was the Danish government’s decision in 2017 to appoint an ‘ambassador’ to the tech companies in Silicon Valley, but it’s clear that some other administrations share the same delusions.

Marietje Schaake, the former MEP who is now International policy director at Stanford’s Cyber Policy Center, has noted this too.

Last month, Microsoft announced it would open a “representation to the UN”, while at the same time recruiting a diplomat to run its European public affairs office. Alibaba has proposed a cross-border, online free trade platform. When Facebook’s suggestion of a “supreme court” to revisit controversial content moderation decisions was criticised, it relabelled the initiative an “oversight board”. It seems tech executives are literally trying to take seats at the table that has thus far been shared by heads of state.

At the annual security conference in Munich, presidents, prime ministers and politicians usually share the sought-after stage to engage in conversations about conflict in the Middle East, the future of the EU, or transatlantic relations. This year, executives of Alphabet, Facebook and Microsoft were added to the speakers list.

Facebook boss Mark Zuckerberg went on from Munich to Brussels to meet with EU commissioners about a package of regulatory initiatives on artificial intelligence, data and digital services. Commissioner Thierry Breton provided the apt reminder that companies must follow EU regulations — not the other way around.

In a brisk OpEd piece in yesterday’s Financial Times, Schaake reminds tech bosses that if they really want change, there is no need to wait for government regulation to guide them in the right direction. (Which is their current mantra.) They own and totally control their own platforms. They can start in their own “republics” today. Nothing stops them proactively aligning their terms of use with human rights, democratic principles and the rule of law. When they deploy authoritarian models of governing, they should be called out. “Instead of playing government”, she writes,

they should take responsibility for their own territories. This means anchoring terms of use and standards in the rule of law and democratic principles and allowing independent scrutiny from researchers, regulators and democratic representatives alike. Credible accountability is always independent. It is time to ensure such oversight is proportionate to the power of tech giants.

Companies seeking to democratise would also have to give their employees and customers more of a say, as prime “constituents”. If leaders are serious about their state-like powers, they must walk the walk and treat consumers as citizens. Until then, calls for regulations will be seen as opportunistic, and corporations unfit to lead.

Bravo! Couldn’t have put it better myself.

So, basically, we’re screwed

Really sobering article in the FT by Martin Wolf. Here’s the gist:

We live in a fossil-fuel civilisation. There have been two energy revolutions in human history: the agricultural revolution, which exploited far more incident sunlight; and the industrial revolution, which exploited fossilised sunlight. Now we must return to incident sunlight — solar energy and wind — along with nuclear power.

Discussions last week at the Oslo Energy Forum clarified things for me. My principal conclusion was that a transformation from our current energy system to a different one is the only option. Some suggest we should halt growth as well. But this would not only be impossible, it would also not be nearly enough.

Over the past three decades CO2 emissions per unit of global output have been falling at a little below 2 per cent a year. If this were to continue and world output were to stagnate, global emissions would fall by 40 per cent by 2050 — far too little. Relying on actual reductions in output, in order to cut emissions by, say, 95 per cent, by 2050, would require a fall in world output of roughly 90 per cent, bringing global output per head back to 1870 levels.

Since we’re not going deliberately to go back to 1870 (all those stovepipe hats), we have to stop burning fossil fuels, period — and make a transition to a non-carbon economy. Wolf thinks that, in principle, this might be possible. But,

A zero-carbon economy would require about four to five times as much electricity as our present one, all from non-carbon-emitting sources. In running such an economy, hydrogen (much of it produced by electrolysis) would play an essential role. Hydrogen consumption might jump 11-fold by 2050.

In many sectors, the costs of decarbonisation are (or soon will be) competitive. Yet in some, they will not be. There will need to be incentives and regulations to force the shift. In order to avoid merely moving production, in its most emissions-intensive forms, elsewhere, it will be essential to impose offsetting taxes on imports from jurisdictions that refuse to support the needed changes.

Note the last sentence and ask yourself what are the chances of this happening in the world as we know it?

Summing up: we could do it, but we won’t. I’ve argued for a long time that we need a theory of incompetent systems — i.e. systems that can’t fix themselves.

Monday 17 February, 2020

Quote of the Day

In this election there are two sides. One side believes in the rule of law, the other doesn’t. Everything else, to be settled later, once the rule-of-law is re-established.

- Dave Winer

_____________________________

My review of Andrew Marantz’s new book — Antisocial

On today’s Guardian. It’s a sobering read.

There has always been a dark undercurrent of white supremacism in some sectors of American culture. It was kept from public view for decades by the editorial gatekeepers of the old media ecosystem. But once the internet arrived, a sophisticated online culture of conspiracy theorists, racists and other malign discontents thrived in cyberspace. But it stayed below the radar until a fully paid-up conspiracy theorist won the Republican nomination. Trump’s candidacy and campaign had the effect of “mainstreaming” that which had previously been largely hidden from view. At which point, the innocent public began to see and experience what Marantz has closely observed, namely the remarkable capabilities of extremist “edgelords” to weaponise YouTube, Twitter and Facebook for destructive purposes.

One of the most depressing things about 2016 was the apparent inability of American journalism to deal with this pollution of the public sphere. In part, this was because they were crippled by their professional standards. It’s not always possible to be even-handed and honest. “The plain fact,” writes Marantz at one point, “was that the alt-right was a racist movement full of creeps and liars. If a newspaper’s house style didn’t allow its reporters to say so, then the house style was preventing its reporters from telling the truth.” Trump’s mastery of Twitter led the news agenda every day, faithfully followed by mainstream media, like beagles following a live trail. And his use of the “fake news” metaphor was masterly: a reminder of why, as Marantz points out, Lügenpresse – “lying press” – was also a favourite epithet of Joseph Goebbels.

Frank Ramsey

Frank Ramsey was a legend in Cambridge as one of the brightest young men of his time. He died tragically young (he was 26) in 1930, from an infection acquired from swimming in the river Cam. Now there’s a new biography of him by Cheryl Misak. Here’s part of her blurb about him:

The economist John Maynard Keynes identified Ramsey as a major talent when he was a mathematics student at Cambridge in the early 1920s. During his undergraduate days, Ramsey demolished Keynes’ theory of probability and C.H. Douglas’s social credit theory; made a valiant attempt at repairing Bertrand Russell’s Principia Mathematica; and translated Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, and wrote a critique of the latter alongside a critical notice of it that still stands as one of the most challenging commentaries of that difficult and influential book.

Keynes, in an impressive show of administrative skill and sleight of hand, made the 21-year-old Ramsey a fellow of King’s College at a time when only someone who had studied there could be a fellow. (Ramsey had done his degree at Trinity).

Ramsey validated Keynes’ judgment. In 1926 he was the first to figure out how to define probability subjectively and invented the expected utility that underpins much of contemporary economics.

I’d never heard of Ramsey until I came on Keynes’s essay on him in his wonderful collection, Essays in Biography, published in 1933. (One of my favourite books, btw.) Given that Keynes himself was ferociously bright, the fact that he had such a high opinion of Ramsey was what made me sit up. Here’s an extract that conveys that:

Seeing all of Frank Ramsey’s logical essays published together, we can perceive quite clearly the direction which is mind was taking. It is a remarkable example of how the young can take up the story at the point to which the previous generation had brought it a little out of breath, and then proceed forward without taking more than about a week thoroughly to digest everything which had been done up to date, and to understand with apparent ease stuff which to anyone even 10 years older seemed hopelessly difficult. One almost has to believe that Ramsay in his nursery year near Magdalene1 was unconsciously absorbing from 1903 to 1914 everything which anyone may have been saying or writing from Trinity.

(Among the people in Trinity College at the time were Bertrand Russell, A.N. Whitehead and Ludwig Wittgenstein.)

The hacking of Jeff Bezos’s phone

Interesting (but — according to other forensic experts — incomplete) technical report into his the Amazon boss’s smartphone was hacked, presumably by someone working for the Saudi Crown Prince.

_____________________________________________

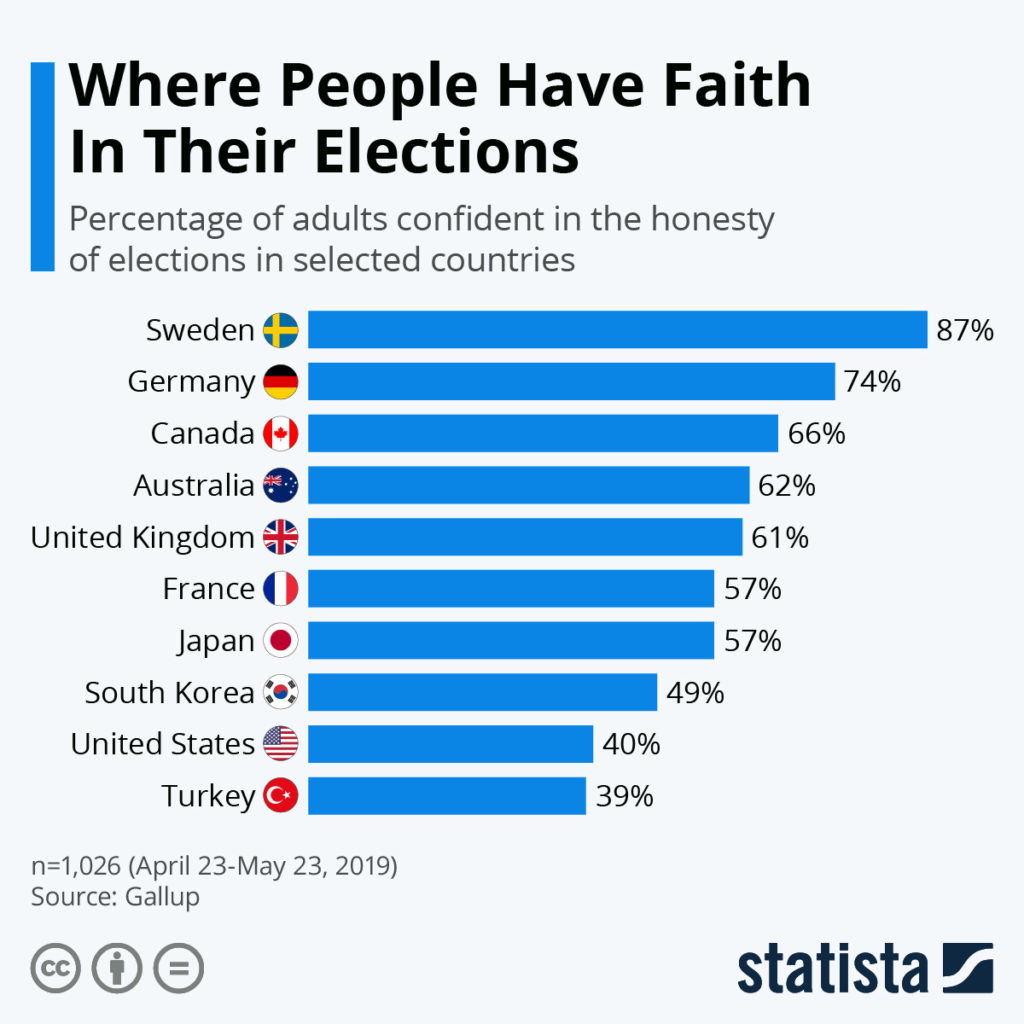

Where people have faith in their elections

The U.S. public’s confidence in elections is one of the worst of any wealthy democracy, according to a recently published Gallup poll. It found that a mere 40 percent of Americans have confidence in the honesty of their elections. As low as that figure is, distrust of elections is nothing new for the U.S. public.

The research found that a majority of Americans have had no confidence in the honesty of elections every year since 2012 with the share trusting the process at the ballot box sinking as low as 30 percent during the 2016 presidential campaign. Gallup stated that its 2019 data came at a time when eight U.S. intelligence agencies confirmed allegations of foreign interference in the 2016 presidential election and identified attempts to engage in similar activities during the midterms in 2018.

This chart shows how the U.S. compares to other developed OECD nations with the highest confidence scores recorded across Northern Europe and Finland, Norway and Sweden best-ranked.

_________________________________________

David Spiegelhalter: Should We Trust Algorithms?

As the philosopher Onora O’Neill has said (O’Neill, 2013), organizations should not try to be trusted; rather they should aim to demonstrate trustworthiness, which requires honesty, competence, and reliability. This simple but powerful idea has been very influential: the revised Code of Practice for official statistics in the United Kingdom puts Trustworthiness as its first “pillar” (UK Statistics Authority, 2018).

It seems reasonable that, when confronted by an algorithm, we should expect trustworthy claims both:

about the system — what the developers say it can do, and how it has been evaluated, and

by the system — what it says about a specific case.

Terrific article

-

Ramsey’s father was Master of Magdalene. ↩