This comes to us via the you-couldn’t-make-it-up department.

The National Security Agency and the Department of Homeland Security have issued “cease and desist” letters to a novelty store owner who sells products that poke fun at the federal government.

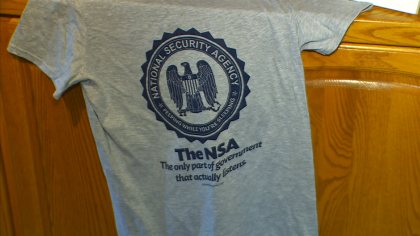

Dan McCall, who lives in Minnesota and operates LibertyManiacs.com, sells T-shirts with the agency’s official seal that read: “The NSA: The only part of government that actually listens,” Judicial Watch first reported.

Other parodies say, “Spying on you since 1952,” and “Peeping while you’re sleeping,” the report said.

Federal authorities claimed the parody images violate laws against the misuse, mutilation, alteration or impersonation of government seals, Judicial Watch reported.

I particularly admire the crack about the NSA being “the only part of the government that actually listens”.

Brian, who told me about the first link, also pointed me to a fuller account about the artist, Dan McCall who came up with the tee-shirt.

What McCall meant as pure parody, apparently wasn’t very funny to bureaucrats at the NSA.

While he calls it parody they call a violation of the spy agency’s intellectual property.

“Because when you’re pointing straight at an organization or making fun at it, turning it on itself, that is classic parody,” he said.

The agency ordered him to cease and desist and forced his T-shirts off the market.

Hmmm… I’d have thought that he’d have a good First Amendment and Fair Use case. But maybe m’learned friends think not.