This morning’s Observer column:

When the internet first entered public consciousness in the early 1990s, a prominent media entrepreneur described it as a “sit up” rather than a “lean back” medium. What she meant was that it was quite different from TV, which encouraged passive consumption by a species of human known universally as the couch potato. The internet, some of us fondly imagined, would be different; it would encourage/enable people to become creative generators of their own content.

Spool forward a couple of decades and we are sadder and wiser. On any given weekday evening in many parts of the world, more than half of the data traffic on the internet is accounted for by video streaming to couch potatoes worldwide. (Except that many of them may not be sitting on couches, but watching on their smartphones in a variety of locations and postures.) The internet has turned into billion-channel TV.

That explains, for example, why Netflix came from nowhere to be such a dominant company. But although it’s a huge player in the video world, Netflix may not be the biggest. That role falls to something that is rarely mentioned in polite company, namely pornography…

Read on So here we are, living in the era of the lean-back internet—an online world that mirrors and amplifies the passivity of old-school television, but with endless options and constant availability. The utopian promise that the internet would empower a generation of active creators has largely given way to a reality where algorithm-driven content streams lull us into hours of auto-play consumption.

The remarkable thing is not just how thoroughly video has colonized the web, but also how quietly dominant forms like pornography have shaped infrastructure, business models, and even innovation in streaming technology. This is not exactly the vision that early digital idealists had in mind. Instead of a participatory, democratic media ecosystem, we’ve built a data-intensive entertainment engine that caters to convenience, anonymity, and relentless gratification.

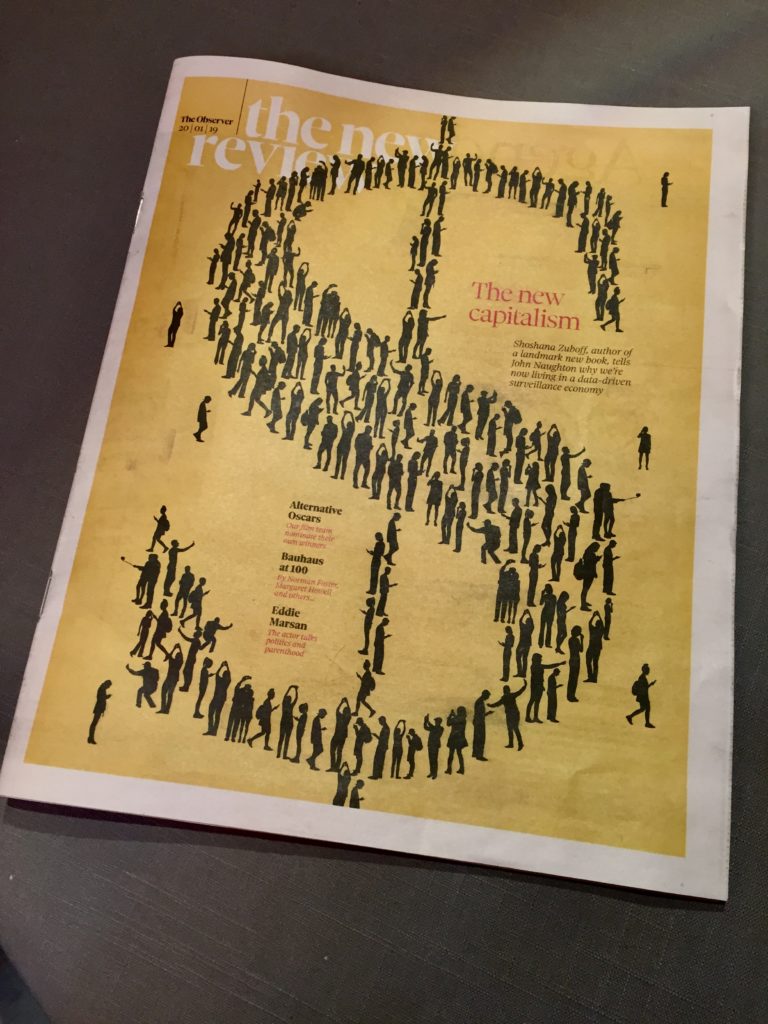

Of course, with this shift comes a significant concern: privacy. While the internet delivers content faster and in greater volumes than ever before, it also exposes its users to tracking, profiling, and surveillance—often without their knowledge. This is especially true for people who access sensitive or adult content and assume their activity is invisible.

The digital world is vast, but not all parts of it are equally open to everyone. From social media platforms to streaming sites, content is often restricted based on geographic location or local regulations. This not only limits free expression but also blocks access to valuable information. VPNs help level the playing field by letting users change their virtual location and avoid censorship. Whether you’re traveling or living in a country with strict controls, you can use a VPN to unblock Twitter, stay informed, and join global conversations without restrictions.

Moreover, using a VPN isn’t just about access—it’s also about reclaiming control over your digital footprint. Many online platforms collect and share user data for advertising or analytics, often without clear consent. A reliable VPN helps mask your IP address, reducing unwanted tracking and enhancing your anonymity. With one simple tool, users can take back a sense of agency online—choosing when, where, and how they connect to the world.

It shields browsing activity from prying eyes, bypasses regional content restrictions, and gives users the confidence to explore the internet without fear of exposure or throttling. If you value the freedom to explore this billion-channel universe safely, it’s worth taking a moment to view vpn app options that prioritize both speed and security. Because if the internet is going to be our collective couch, the least we can do is protect the space we’re reclining in.